Canada’s community colleges are often thought of as places to learn “vocational” skills. But what counts as a “vocational” skill these days doesn’t always line up with popular perceptions. One area in which this is particularly true is with respect to the trades. My associate Lori McElroy has been doing some interesting work in this respect which I think is worth sharing.

When we think of colleges and trades, we often think of a lot of programs that are not actually “college level.” There’s apprenticeship technical training which takes place in colleges: roughly 150,000 students per year coming for eight weeks each on average. In FTE terms, these make up less than 5% of what colleges do. There are technical pre-employment programs of less than a year’s length, but these are increasingly rare and not even considered post-secondary level by Statistics Canada.

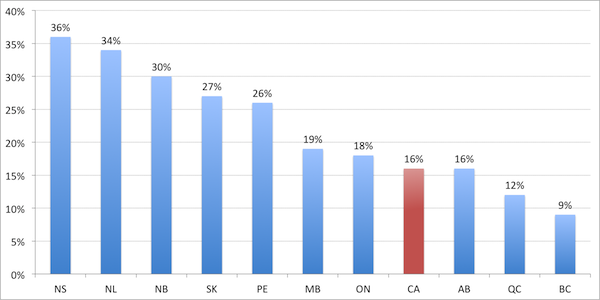

Within college-level programs – that is, diplomas and certificates – there are of course large numbers of trades and technical programs, but they are a very long way from being the mainstream of college programming. Nationally, only 16% of students in diploma and certificate programs (a definition which excludes all those university-transfer programs in Alberta and B.C. as well as academic DECs in Quebec) are in technical and trades-related programs. And this figure varies substantially from one province to another, ranging from 36% in Nova Scotia to just 9% in British Columbia.

Figure 1: Proportion of Diploma- and Certificate-Program Students Enrolled in Technical and Trade-Related Programs, 2008-09

Source: Statistics Canada, Postsecondary Student Information System

So if trades aren’t the mainstay of colleges, what is? Well, a look at Statistics Canada enrolment data shows pretty clearly that it’s programs that have substantial overlap with university studies.

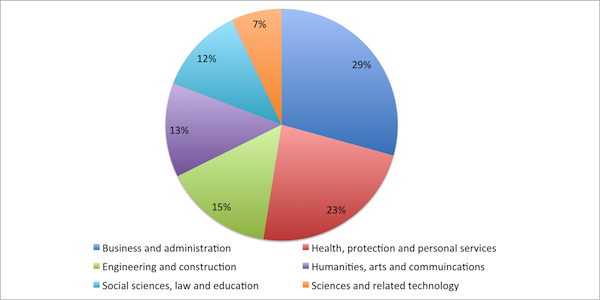

Figure 2: College Enrolment by Program Type, 2008-09

Source: Statistics Canada, Postsecondary Student Information System

Nearly three out of ten students are in some kind of business program; and another 32% are in some kind of program related to arts, fine arts, social sciences or sciences. In other words, over 60% of college students studying in areas which are hardly a million miles from what universities do. Obviously, these programs are shorter and more applied than university degrees, but the actual subject matter is reasonably close.

It’s reasonable to look at this as evidence of “academic drift” among colleges. But that implies that the drift has all been one way. Take a look at new programs offered by universities over the last 30-40 years and it becomes quickly clear that the charge of “vocational drift” among universities is at least as valid. The world of work has changed and a lot of new applied fields lie somewhere between where universities and colleges used to be – gradually, they are converging in the middle.

Trades will always have an important place in post-secondary education, of course. But the new approach to vocational training seems to be involve a much softer set of skills.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Part of the issue this post alludes to is the use of the term “vocational” and its incorrect association with skill trades training. In this post you are correctly formulating the proper notion of vocational education as that which is close to the labour market. What knowledge and skills are being learned is irrelevant – what’s important is how they are being taught and learned and, perhaps most importantly, why. Delivering education and training demanded by the labour market has always been the job of colleges and not universities. Universities have long touted the development of the complete person according to the notions of Humboldt and Newman. And so the term “vocational education” receives an interestingly short shrift from many in higher education – some turn up their noses at the thought – while at the same time they add practicums, internships, and co-op education placements and willingly promote their programs by indicating how many of their graduates get jobs in their field. If education and training for an occupation isn’t vocational education, then what is?

For a long time, we in the college and institute sector have been accused of academic drift and cautioned to stay within our realm when really, we should have been saying the same to our elevated brethren in academia as they move toward career preparation and away from bildung. Going further, this alignment of higher education with the labour market leads directly to marketization of research and hence academic capitalism – which leads even further to considerations of the ultimate purpose of higher education or even, as you so correctly point out, the entire notion of the university. Perhaps it is time for something new. But if so, please let those with more experience doing it create the new model.