Yesterday, I introduced the equation X = aϒ/(b+c) as a way of setting overall teaching loads. Let’s now use this to understand how funding parameters drive overall teaching loads.

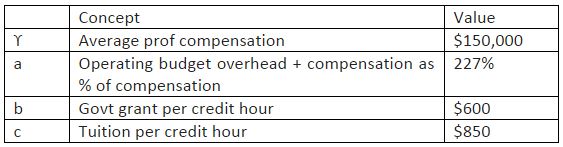

Assume the following starting parameters:

Where a credit hour = 1 student in 1 class for 1 semester.

Here’s the most obvious way it works. Let’s say the government decides to increase funding by 10%, from $600 to $660 (which would be huge – a far larger move than is conceivable, except say in Newfoundland at the height of the oil boom). Assuming no other changes – that is, average compensation and overhead remain constant – the 10% increase would mean:

X= 2.27($150,000)/($600+$850) = 235

X= 2.27($150,000)/($660+$850) = 225

In other words, a ten percent increase in funding and a freeze on expenditures would reduce teaching loads by about 4%. Assuming a professor is teaching 2/2, that’s a decrease of 2.5 students per class. Why so small? Because in this scenario (which is pretty close to the current situation in Ontario and Nova Scotia), government funding is only about 40% of operating income. The size of the funding increase necessary to generate a significant effect on teaching loads and class sizes is enormous.

And of course that’s assuming no changes in other costs. What happens if we assume a more realistic scenario, one in which average salaries rise 3%, and overhead rises at the same rate?

X= 2.27($154,500)/($660+$850) = 232

In other words, as far as class size is concerned, normal (for Canada anyway) salary increases will eat up about 70% of a 10% increase in government funding. Or, to put it another way, one would normally expect a 10% increase in government funding to reduce class sizes by a shade over 1%.

Sobering, huh?

OK, let’s now take it from the other direction – how big an income boost would it take to reduce class sizes by 10%? Well, assuming that salary and other costs are rising by 3%, the entire right side of the equation (b+c) would need to rise by 14.5%. That would require an increase in government funding of 35%, or an increase in revenues from students of 25% (which could either be achieved through tuition increases, or a really big shift from domestic to international enrolments), or some mix of the two; for instance, a 10% increase in government funds and a 17% increase in student funds.

That’s more than sobering. That’s into “I really need a drink” territory. And what makes it worse is that even if you could pull off that kind of revenue increase, ongoing 3% increases in salary and overhead would eat up the entire increase in just three years.

Now, don’t take these exact numbers as gospel. This example works in a couple of low-cost programs (Arts, Business, etc.) in Ontario and Nova Scotia (which, to be fair, represent half the country’s student body), but most programs in most provinces are working off a higher denominator than this, and for them it would be less grim than I’m making out here. Go ahead and play with the formula with data from your own institution and see what happens – it’s revealing.

Nevertheless, the basic problem is the same everywhere. As long as costs are increasing, you either have to get used to some pretty heroic revenue assumptions (likely involving significant tuition increases) or you have to get used to the idea of ever-higher teaching loads.

So what are the options on cost-cutting? Tune in tomorrow.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Now redo this factoring in the large number of courses taught by contract faculty. That should be your part 3.

It is. Patience.

So … an average salary of $150K? That feels more than a little high to me, so I’d be curious about that piece in your formula. That’s almost $50K higher than the average salary at UVic, for example, which is my school, and I’m sure there’s not a university in the country with an average professor salary of $150K.

Hi Richard. not salary: compensation. includes benefits, payroll taxes.