Yesterday, I described a variety of different type of innovation organizations around the world and suggested that part of the problem in Canada is that the federal government has difficulty understanding any kind of innovation agency whose mission is not “give out more gobs of cash”, because in today’s Ottawa it is expenditure which indicates virtue, not the outcomes of those expenditures.

So, given that, how do we evaluate two significant recent changes to the innovation ecosystem in Canada?

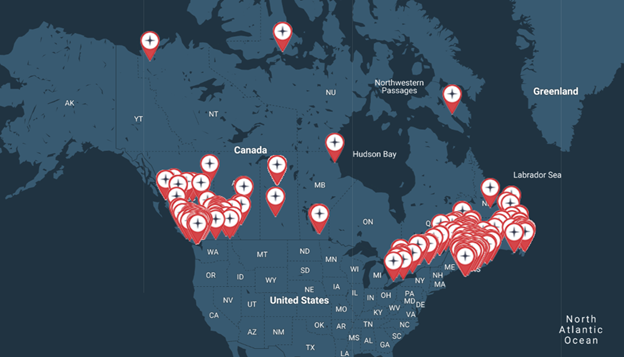

The first change is pretty cosmetic. The five superclusters have had their funding renewed for another few years, but with two changes. First, we are no longer supposed to call them Superclusters: henceforth, they shall be known as “Global Innovation Clusters”. And second, ISED seems to have required them all to ditch their regional development aspects and become national in scope. I can’t find a press release or anything to show this but it’s plain as day if you look at the clusters’ website. For instance, the Ocean Supercluster, which was ferociously Atlantic in its original format, now proudly shows off “Canada’s Ocean Assets” thusly:

This is a fascinating development because it completely undermines the original logic of the program. The WHOLE POINT of calling them clusters (super-, global-, whatever) was because they were meant to build on the logic of economic clusters like Silicon Valley, the North Carolina Research Triangle, etc., all of which were based on principles of PHYSICAL PROXIMITY, a la Alfred Marshall. So, what ISED has done is some ass-backwards re-labelling: they changed “super”, which was silly but inoffensive, while holding fast to the no-longer-even-vaguely-true word cluster. What we should be calling them is industrial granting councils, because basically that’s what they are.

And then there is the Canada Innovation Corporation, Regular readers may recall that in Budget 2022, the federal Liberals backed out of their commitment to create a Canadian equivalent of DARPA (only without a focused mission like defence, just “do cool stuff!”) and instead opted to create a different kind of agency focused more directly on technological diffusion across wide swathes of industry, along the lines of Finland’s Funding Agency for Innovation (Tekes, since folded into Business Finland) and the Israel Innovation Authority (IIA). And then, silence, until last month when the government finally announced what the new organization would look like in this blueprint document.

It’s a difficult document to summarize (as it is stuffed with some opaque jargon), but the basics are that this agency is only partly about providing funding: it is also about the delivery of technical advisory services (which includes making linkages between corporations and researchers at universities and colleges) and the creation of business foresight and experimentation functions. That’s close to how this project was sold in the 2022 Budget. But then, for some reason, the government decided to carve out the Industrial Research Assistance Program (IRAP) from the National Research Council and graft it on to this new organization. This, to put it mildly, was not in the original plan.

I can kind of see the logic at work here: IRAP is the one part of the government that has lots of national industrial contacts, so using their expertise to accelerate staffing-up makes sense. Theoretically, bringing in IRAP means a new organization can hit the ground running. The problem is that one of the big features of the DARPA/Tekes/IIA model is that much of their strength stems from being small, nimble, and independent from government. And while legally this organization is arms-length from government, when the first 275 or so employees of a “nimble” new organization are federal government employees, the culture is almost guaranteed to be that of a cautious public service, rather than the agile and risk taking culture, which was key to the Tekes/IIA success in the first place.

(And, perhaps more to the point, if IRAP was sufficiently bad at industrial technology diffusion to the point where a whole new agency needed to be created, why on earth would you hand over the new replacement agency to exactly the people whose work has just been deemed less than adequate? Seems deeply odd.)

In short: the reasons to like this agency are that a) it’s actually directly focused on innovation at the level of the firm, which is a refreshing change from the usual underpants gnomes thinking that tends to dominate Canadian innovation policy and b) its remit at least in theory extend beyond mere funding and extend into market-shaping activities. The reasons to be skeptical are that these kinds of institutions have only tended to work well when staffed by non-governmental outsiders who bring speed, agility and entrepreneurialism to the table, and boy howdy, making ex-NRCers the majority of the organization’s first 275 employees is likely to steer the organizational culture in a very different direction.

I am, as a result, less optimistic about this organization having a real impact than I was a year ago. But let’s give it a whirl: it can’t be worse than what we’re already doing.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post