Canadians are regularly bombarded with stories about “rising tuition” and “ever-mounting student debt”, the implication always being that the middle-class is being priced out of higher education, access to education is being threatened, etc. If these stories were true, it would indeed be worrying. The problem is, they are mostly nonsense and fuelled by ignorance of just how much Canada’s system of student assistance has grown and changed over the past couple of decades.

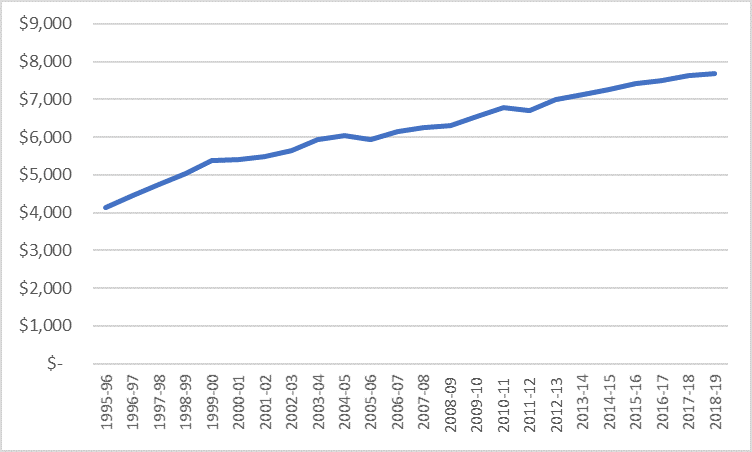

As figure 1 shows, tuition has been rising at about 2% per year after inflation since 2000 (see Figure 1). That’s well down on the 5-7% increases we saw regularly in the 1990s, and moreover it is a steady, controlled and manageable rise that allows most families to plan ahead to meet educational costs. It’s not cheap, by any means, but it’s not stratospherically high, either.

Figure 1: Average Tuition and Fees, Canadian Universities, 1995-96 to 2018-19 (est), in real $2018

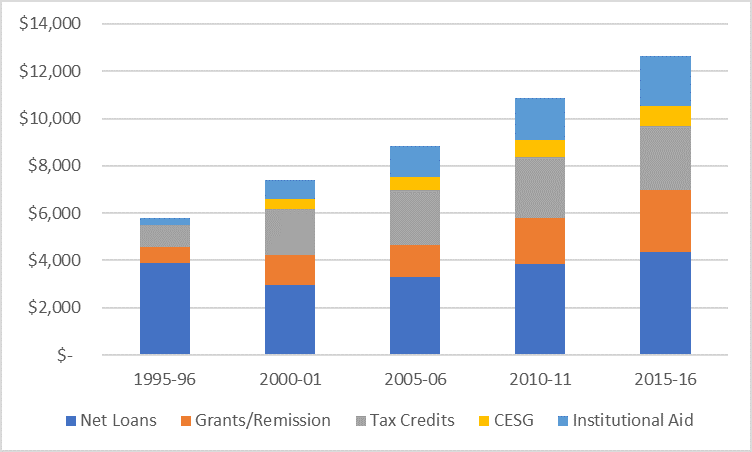

But of course, what matters is not just the sticker price of education, but what students actually pay. And what they pay in practice is nothing like the actual sticker price. Since 2000, total student financial assistance has been rising by approximately 4.5% per year. As figure 2 shows, what 20 years ago was a $5.8 billion/year financial aid system in which two out of every three dollars were loans, is now a $12.7 billion/year system in which only one out of every three dollars is a loan. (note: figure 2 does not take into account post-2015 changes in the Ontario, New Brunswick and the Canada Student Loans Programs which converted over a third of the country’s tax credits into student grants).

Figure 2: Total Student Assistance, Canada, 1995-96 to 2015-16, in real $2016

Statistics Canada data on institutional finance tells us that since 2000, the total amount of tuition and fees collected by universities and colleges increased from $5.8 billion to $12.6 billion. But as we saw yesterday (link), well over $2 billion of that increase – actually probably over $3 billion, but we can’t tell exactly because we have no useful data on international student fees in colleges – came from international students. If we take $3 billion out of the fee increase, then that implies an increase of $3.8 billion in fees since 2000 – compared to a $5.25 billion increase in aid, $3.8 billion of which is in non-loan form. Or, to put this another way: governments and institutions have covered 100% of the cost of all tuition increases since 2000.

[the_ad id=”12791″]

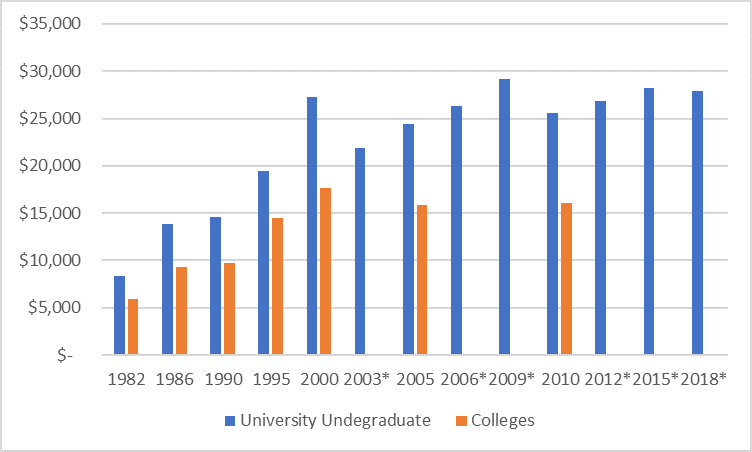

One result of this is that student debt levels, as far as we can tell, are essentially unchanged since the year 2000. We have two data sources for looking at student debt over time: the National Graduates Survey (NGS), which surveys every fifth (formerly fourth) graduating class. It is high quality data but suffers from being brutally out of date: right now, the most recent observation is from 2010. The second source is the Canadian Undergraduate Survey Consortium (CUSC)’s triennial survey of graduating students, which is fantastic in that its data is always pretty current, but less so in that it has a slightly inconsistent sample (consortium members vary a bit from survey to survey), has low participation in Quebec and does not include colleges. Figure 3 shows average student among those students who incurred debt from both of these sources (note, both NGS and CUSC suggest incidence of debt is around 50% in universities and falling over time; NGS suggests college debt incidence is in the 30-35% range and falling over time)

Figure 3. Average Debt Levels, Students With Debt Only, 1982 to 2018 (in constant $2018)

*indicates source = CUSC, otherwise source = NGS

There is a lot of noise in figure 3, but basically what it appears to show is a significant run-up in student debt levels in the 1990s, but a flattening out in real terms since 2000. Of the six national surveys that have been undertaken since 2006, the value for undergraduate debt has moved around in a relatively narrow band between $24,00 and $29,000, with a mean value of just under $27,000.

Here’s the reality. Tuition has been rising over time, but student aid has been rising even faster. 100% of domestic tuition increases have been balanced off with different types of aid to non-repayable aid to students, and debt levels are essentially unchanged from where they were at the turn of the millennium – and this during a period where median family incomes were rising at about 1% per year on average. If you care about facts, it is actually very difficult to talk about affordability in terms other than victory.

Now, while all those platitudes you hear about “ever-increasing student debt” are indeed false, that doesn’t mean there isn’t still a lot of room for improvement in student aid. We probably give too much money to the upper-middle class and not enough to students from poor backgrounds. Even after the 2016 reforms, we still have too much money in tax-based measures and not enough in up-front grants. And there’s certainly room for discussion about whether we have the need/merit balance right.

But to get to those important discussions, we need to focus on facts and not slogans – particularly ones which are factually inaccurate. There’s no time like the present to start.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

The bigger question is: Should a significant percentage of postsecondary students have to go into debt for their education simply because they and their families have no other way to pay?