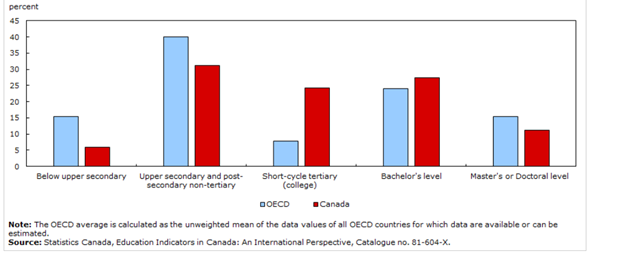

On Monday, Statscan put out a “Portrait of Youth and Education in Canada,” which includes the following graph accompanied by a note to the effect that Canada has one of the highest post-secondary attainment rates in the world because of our high community colleges/polytechnic participation rates. It was accompanied by the following graph:

Figure 1: Highest Level of Educational Attainment, 25 to 34-year-olds, Canada and OECD average 2019, as per Statistics Canada

Now, I know this line of argument. I use it myself once or twice a year, both because I am a bit lazy and because I genuinely think our college sector is pretty awesome. But it’s not exactly true because it conflates “post-secondary education” with “tertiary education” when they are not the same at all. Canada looks very good in comparisons of the former; much less so in the latter.

The problem lies in various attempts to line up national statistical categories with international ones. Canadians (and others I suspect) tend to count things with institutions in mind: we have X many students in college, Y students in universities, etc. But international schema don’t work that way. UNESCO’s International System for the Classification of Education (ISCED) focuses not on institutions, but rather on “levels of education”, a simplified version of which I present here:

| Level | Name/Description |

| 0 | Early Childhood Education |

| 1 | Primary Education |

| 2 | Lower Secondary |

| 3 | Upper Secondary |

| 4 | Post-Secondary Non-Tertiary |

| 5 | Short-cycle Tertiary |

| 6 | Bachelor’s or equivalent |

| 7 | Master’s or equivalent |

| 8 | Doctorate or equivalent |

Levels 0, 1, 6, 7 and 8 are all reasonably straightforward, but the others are actually clear as mud. In Canada for instance, 2 and 3 are often conflated in ways they would not be in other countries. A lot of the vocational skills programs that we provide after high school (and hence get called level 4) are delivered in high school elsewhere. And the line between 4 and 5 can be very thin indeed. Technically, 4 is comprised of “programmes providing learning experiences that build on secondary education and prepare for labour market entry and/or tertiary education” while 5 is “short first tertiary programmes that are typically practically-based, occupationally-specific and prepare for labour market entry, but which may also provide a pathway to other tertiary programmes.” Thin difference, but it’s there.

Now, here’s the thing: as is quite clear from Figure 1, above, when making international comparisons, Statscan equates level 5, or “short-cycle tertiary” with “college”. But this isn’t actually accurate, and we know this because Statscan itself categorizes college enrolments by ISCED level. In fact, Canadian college enrolment only became majority ISCED 5 or higher about a decade ago – and is only narrowly so.

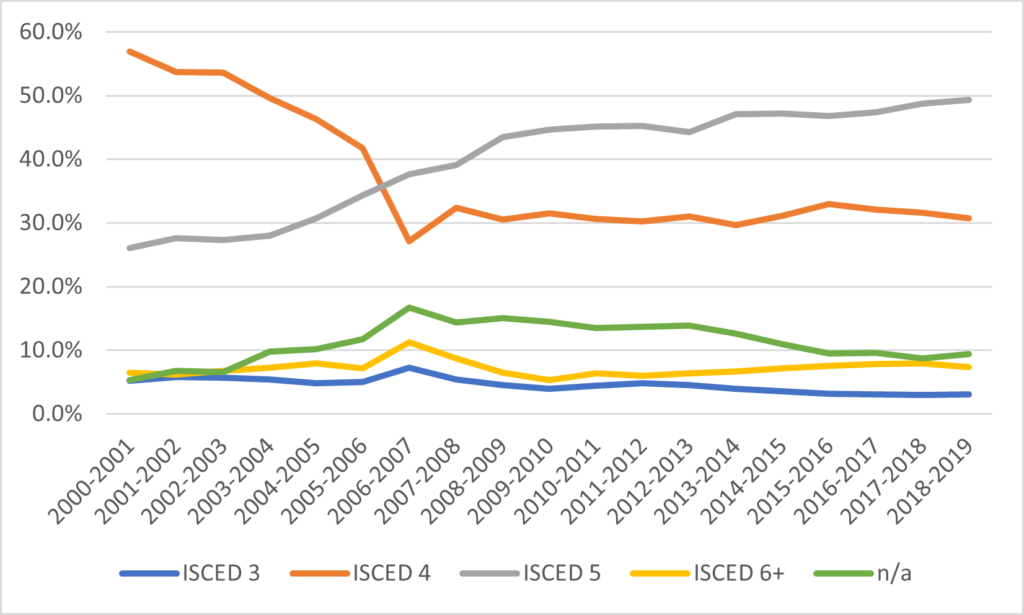

Figure 2: Total College Headcount Enrolment, by ISCED Level, 2000-2001 to 2018-19

Basically, Canadian colleges are always post-secondary institutions, but they are not always tertiary ones. Internationally, this is a very anomalous situation – strictly speaking only New Zealand polytechnics and Wānangas are in a similar situation. The American community college system is arguably similar, but because nearly all their two-year programs are meant to ladder into four-year ones, they all get described as ISCED 5 even though they are frequently hard to distinguish from Canadian ISCED 4 programs (you see how tricky this stuff is?).

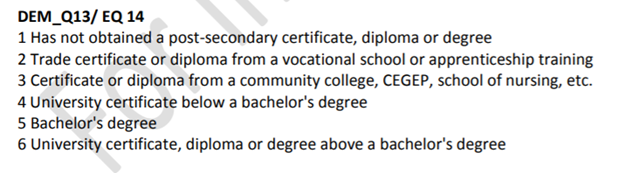

OK, I can see a some of your brows wrinkling in confusion: “wait a minute”, you say, “if Stastcan knows how many college students are studying at various ISCED levels, why does it have trouble reporting on attainment rates by ISCED level”? And the answer is that while enrolments are based on relatively clean administrative data, attainment rates are based on messier survey data – specifically, the monthly Labour Force Survey. Note how the Labour Force Survey allows individuals to answer questions about their educational attainment level:

As you can see, answers 2 and 3 are not quite equivalent to ISCED levels 4 and 5, because – for instance – if some gets a vocational certificate at a community college, they are likely to answer 3, thus rendering someone who is pretty obviously and ISCED 4 graduate indistinguishable from college graduates who were in ISCED 5 programs. LFS effectively can’t distinguish between the two. And this gives rise to the situation where Statscan just says “the hell with it” and reports all college graduates as level 5. Statistics Canada could, if it wished, create some type of reasonably well-informed estimate to split the level 4s and level 5s and give us estimates which are more comparable to actual international norms. But when it comes to international education data, Statscan usually prefers to be precisely wrong rather than generally right.

In short, when trying to do international attainment rate comparisons, just remember that: i) post-secondary and tertiary are not the same thing, ii) Canadian community colleges don’t have easy equivalents to ISCED levels 3 through 5 in other countries, and iii) in consequence, when comparing tertiary attainment rates, it’s probably worth reducing our “short-cycle”/level 5 estimates by at least half (less for recent graduates, more for older ones). It’s probably not quite that exact (the presence of immigrants with levels 4 or 5 education picked up in their countries of origin complicate things), but it’s close. Following these rules puts Canada’s “true” tertiary attainment rate among 24-35 year olds not at a world-beating 64%, but rather something in the low-to-mid-50s, closer to the United States (52%), Australia (55%) and the United Kingdom (56%) – that is to say, a little bit above the OECD meeting but a long way off the top of the table. Basically, we go from having an outstanding system to one which is just middling-good.

2 Responses

Where do CEGEPs fit in the ISCED scale? 3? 4?