If you’ve been watching the American higher education scene for the last couple of years, you will no doubt have noticed a spate of bills wending their way through various state legislatures that are widely understood as attacks on higher education. These include bills weakening tenure, bills making it effectively illegal to teach American history (lest White students feel guilty about the actions of their ancestors), or the defunding of courses on programs on gender or women’s studies. The narrative that is being established is that perceived campus radicalism (either from students or professors) is alienating middle-America (or at least the bits of it that elect Republican legislatures), which is provoking back-lash.

This is not, of course, a new story. If you go back to the late 60s, there was a very similar pattern. As student reaction against the Vietnam War moved from its relatively sedate “teach-in” phase to the more forceful one of demonstrations and occasional violence (e.g the Sterling Hall bombing at Wisconsin), and as the fight for civil rights became accompanied by calls for Black Power (which in campus terms usually meant the introduction of programs of Black Studies and was also accompanied by significant confrontation, such as the yearlong student strike at San Francisco State and the Cornell Afro-American Society’s takeover of the student union building), so too did a “backlash” mount against campuses. Eventually – or so goes this argument – it led to defunding of public higher education, at just the moment when universities were starting to massify. Thus the initial promise of mass higher education as institutions was lost, and they had to resort to charging for their services to back-fill lost federal money.

This, at least, is the story told in a new book by Ellen Schrecker, entitled The Lost Promise: American Universities in the 1960s. This book is very good as a history of American campuses in that troubled decade. Unlike many books on this era, The Lost Promise reaches beyond the usual dozen or so privates and flagship publics to get a real sense of what was happening not just at the “prestige” institutions but also at the “university next door.” And it is reasonably comprehensive, not just tracking the development of student radicalism, but also the trends in disciplinary thought that made things like Black Studies or women’s studies possible.

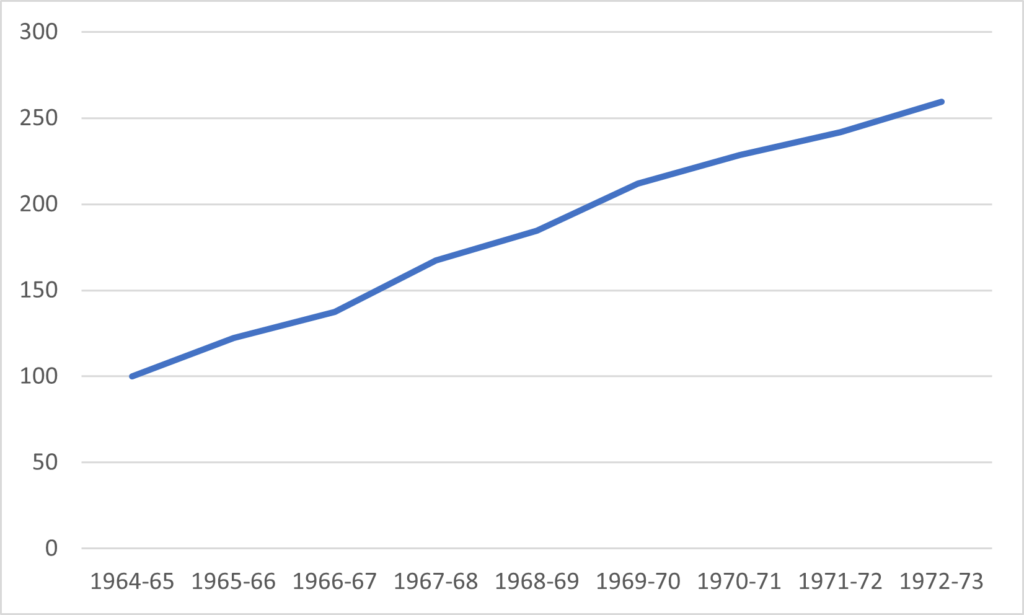

However, while Schrecker excels in the historical aspects of this period, her discussion of finances is, well, problematic. In the book’s introduction and then repeatedly throughout the book, we are told that all these developments on campus eroded public support and that not only did this result in a flood of anti-higher education legislative measures (much like today), this would eventually result in cuts to higher education. But it’s not quite that simple. Check out Figure 1, in which I plot aggregate state support to American universities in real dollars over the period 1964 to 1972, using the “Grapevine” data set produced by the State Higher Education Executive Offices (SHEEO). If you can spot the moment when state governments stopped supporting higher education, you have better eyes than I do.

Figure 1. Indexed Aggregate state transfers to public higher education institutions, 1964-65 to 1972-73 in real dollars (1964-65 = 100)

Now, I haven’t chosen the period 64-72 randomly. It is a period when some pretty key political shifts took place in the US. It is the period, for instance, covered by Rick Perlstein’s excellent Nixonland, whose introduction finished with:

The main character in Nixonland is not Nixon. It is the voter who, in 1964, pulled the lever for the Democrat for president because to do anything else, at least that particular Tuesday in November, seemed to court civilizational chaos and who, eight years later, pulled the lever for the Republican for exactly the same reason.

Given that nearly all the famous campus disruptions, occupations, riots and police shootings happened during the 1968-1972 period, one might expect that to be the period where one would see the funding back-lash. But while the 41% real increase in funding in the period 68-69 to 72-73 was smaller than the 84% in the period 64-65 to 68-69, all you’re really seeing is the rate of growth falling to “really impressive” from its previous “unimaginable and unsustainable.” As evidence of backlash, it’s pretty unconvincing.

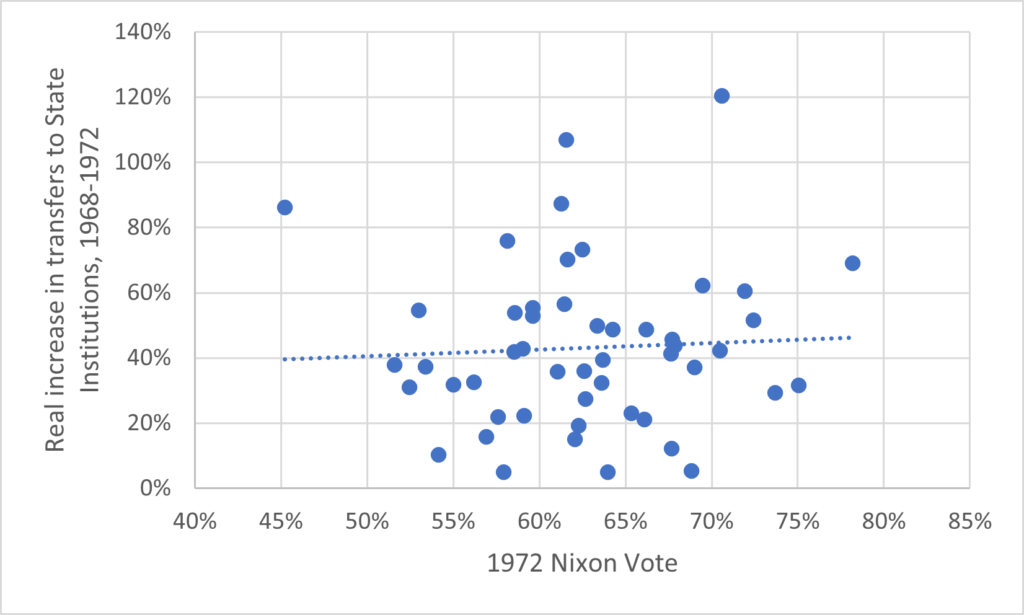

Ah, one might say, well perhaps the backlash was geographically restricted; that is, more pronounced in more conservative areas of the country. Good thought! Now, we can’t really test this on a red state/blue state basis because in the 1972 election, Nixon won every electoral vote except Massachusetts and DC’s. But we can test the theory by looking at real state increases in funding (not a single state reduced funding over this period) vs. Nixon’s share of the vote in 1972, shown in Figure 2. And as it turns out: no, still nothing, state funding increases were not related to the degree of conservatism in the local electorate. Of course, it’s certainly true that in the long run funding did stall and then fall – but that wasn’t really until the Reagan era. But you have to ignore a hell of a lot of variables to claim that an upsurge in campus radicalism in the late 1960s was the direct and proximate cause of a funding decline over ten years later.

Figure 2: State Funding Increase 1968-69 to 1972-73 vs. Percentage of State 1972 Presidential Vote Going to Richard Nixon

Why am I dredging all this up? Well, it’s because of a curious parallel to the present day. As noted above, there is no shortage of weird anti-higher education legislation going through various state legislatures, but – contrary to what you might be hearing, it is not the case that higher education is currently under financial attack. In fact, state support for higher education is up in 2022 by 8% (in nominal terms) over where it was in 2021. Not only that: it’s up in 45 out of 50 states, and the odd five out are an ideologically disparate bunch: Vermont, Hawaii, New Hampshire, Alaska and Wyoming. In other words, the US seems to be in a period very much like the early 1970s, where right-wing state houses enjoy making legislative trouble for higher education while at the same time providing relatively strong support for new funding.

In other words: beware easy narratives. Things are complicated.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

These figures aren’t per student funding, are they? If funding increased by 50%, but enrollments by 100%, universities would be effectively less funded.

Secondly, I don’t think these various efforts to constrain institutions are directed against universities as corporations, but against the true academy, which seeks knowledge for its own sake. Their sponsors would be perfectly content to have a centre of technical invention, offering vocational degrees. Similarly, the bishops of Paris in the thirteen century were content to have a university in their midst, as long as it trained clerics and reinforced the teachings of our Holy Mother the Church, but didn’t want the masters to be free to teach Averroism. Plus ça change…