One perennial topic of interest in Canadian higher education (particularly during recessions) is the subject of Work-Integrated Learning – that is, work experience which is organized by an educational institution and which is incorporated into a student’s educational programme. Today, HESA is releasing a paper by Miriam Kramer and me on how students’ work experiences stack up in terms of learning outcomes that contain some interesting results.

We asked a little over 2,100 students about a variety of work experiences: summer jobs, part-time in-school work, volunteer positions, TAships, RAships, co-ops and various forms of what we call “internships” (which includes practicums, placements, etc.). Specifically, we asked them how much each of the of these experiences might have helped them in terms of reinforcing concepts learned in class, obtaining workplace skills and preparing students for future work. Our goal here was to avoid simply measuring the benefits of programs like co-ops and internships, because it’s pretty clear that there is educational value in all forms of work; what’s important is rather to look at the value-added of such programs.

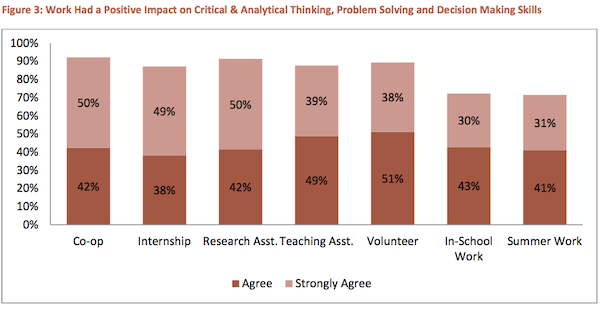

What we found was that in terms of obtaining workplace skills, students reported gaining them more or less equally across all types of jobs – there was no special benefit to work-integrated learning programs. On the other hand, when it comes to reinforcing concepts learned in class and preparing students for future work, there is a clear hierarchy among types of work. Not surprisingly, summer and in-school work were seen as being at the bottom, with co-ops and internships at the top.

That academic programs which mix class-room learning and “real-world” jobs fare best on these measures isn’t a surprise, but two of our other findings were. The first was that research assistantships/academic fieldwork were rated almost as highly as co-ops in terms of reinforcing academic concepts and career preparation. The second was that while summer jobs as a whole rated pretty lousy on those metrics, for the one in six students who said their field of study was the only or best possible one for the summer job they held, the results were indistinguishable from those of co-op programs.

In other words, while co-op is indeed pretty cool, it is possible to replicate co-op’s successes through other means. The high scores received by RAships suggest that placement in “real world” jobs are not key to co-op’s success, and the fact that some types of summer jobs can do the same suggests that co-op’s successes don’t depend solely on the mediation of an institution.

Give the paper a read today. More on the policy implications tomorrow.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

One response to “Beyond Co-op (Part One)”