So, I was in South Africa last week talking to people from various ends of the higher education system. It’s a fascinating place, which is attempting the almost-unimaginably difficult task of creating a single, functional system of education from the wreckage of apartheid.

One key aspect of contemporary South Africa is that genuine political competition is still some ways off. Opposition parties exist, and the ruling alliance is experiencing some strain due to the increasing unhappiness of the main trade union, COSATU, but the fact of the matter is it’s still almost inconceivable the ANC could lose power before 2024 at the earliest. Absent competition, quality of service delivery tends to suffer because government simply doesn’t have its feet to the fire very often. And education is most certainly suffering. In fact, K-12 education is widely pointed to as the file where the ANC has performed the most poorly. Obviously, the legacy of the apartheid-era Bantu education policies place a terrible burden on the system, but nevertheless when surveying the education system as a whole, words like “abysmal” and “train wreck” do spring to mind.

Only about half of all students finish twelve years of high school (most drop out between year 10 and year 12). Of those, only about three-quarters pass the matriculation exams. Of those, only thirty percent achieve a sufficiently good matric that they qualify (on paper at least) to attend university. The result is that only about one-in-eight youth is actually eligible to attend university. And of course within that one-eighth, whites and Indians are significantly over-represented. Participation rates for whites are up around 50%; for Africans, they languish at around 10%.

Dropout rates within university are also a problem. At best, only about half of students complete their three-year course of studies within six years, meaning that at the end of this very leaky pipeline, one finds an attainment rate of around 6%; nowhere near what is needed to run an advanced economy. As a result, South Africa’s economy is not advanced in any sort of comprehensive way – what it has is a thin sliver of a developed economy, laid on top of a much larger economy indistinguishable from what you’d see in the rest of Africa. If you can imagine dropping New Zealand into the middle of Kenya, you’ve more or less got the picture.

New Zealand dropped onto Kenya is a reasonably accurate description of the university system, too. There are a handful of formerly-white institutions (Witswatersrand University, Stellenbosch University, University of Cape Town, etc.), which are basically research universities (only really badly funded). However, a majority of institutions are either historically black or recently-merged (more about mergers next week), which often seek to emulate research institutions, but haven’t even vaguely got the human or financial resources to act that way. Shouldn’t they differentiate, you say? In theory, perhaps, but here you again run into the apartheid legacy: how can anyone argue with a straight face for a system where the only “top” universities (i.e. research intensive ones) are the ones that are historically white?

The money problems are real, too. South Africa’s GDP per capita is about the same as China’s ($6,500 US). But China can support lots of world-class research on that budget because most of its profs don’t speak English that well, and hence have limited mobility. It can pay them well below world rates, and so there is lots left over for lovely new infrastructure, labs, etc. South Africa can’t get away with that. A significant fraction of its academics are quite mobile and liable to leave for Australia, the US, or wherever, at the drop of a hat. Their pay rates therefore have to be at least marginally competitive with those of much, much richer countries, which leaves very little left over for all the other stuff universities need to be excellent.

No simple answers here, but lots of challenges – and increasingly lots of interesting solutions, too. I’ll have more on this next week.

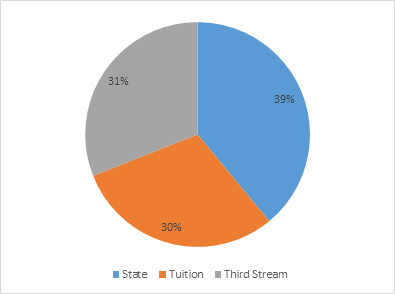

The first area has to do with how institutions raise income. Sub-Saharan African countries tend to fall into two groups: those that are over-reliant on government funding (most of Francophone and Lusophone Africa), and those that are reliant on private fees paid mainly to private institutions or through dual-track tuition systems at public universities (most of Anglophone Africa, especially East Africa). What you don’t tend to see in Africa are universities relying on self-generated non-fee income to fund themselves. Here’s where South African universities’ money comes from:

Figure 1: South African Universities’ Income by Source (Source: Vital Stats, Public Higher Education 2012, Council on Higher Education, South Africa)

One could quibble around the edges with this: if you count all the money government spends on student aid, the state stream is considerably bigger (and the tuition stream smaller), but the really amazing thing is the third-stream income, which comes neither from government or students. At 31%, it’s pretty much the highest percentage of anywhere in the world.

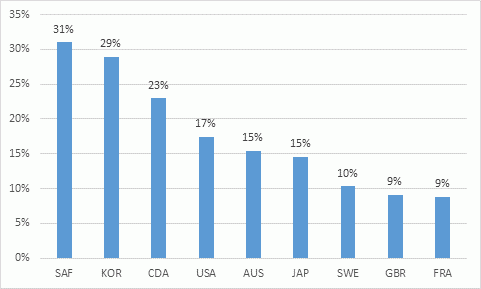

Figure 2: Third-Stream Income as a Percentage of Total University Income, South Africa and Selected OECD Countries (Source: Vital Stats, OECD Education at a Glance 2104, Table B3.1)

Interestingly, South African institutions are achieving this without a significant tradition of charitable giving. This isn’t a US private college situation where the money is all coming from endowments; according to a 2009 survey, endowments account for only about 11% of the money. About a third of it comes from contracts, and over 55% of it comes from things like sales of service.

Sure, the big old (sotto voce: “white”) institutions like Wits and UCT do better on this measure than others (48% and 40%, respectively), but even the poorest institutions (the universities of technology) make 15% of their income this way – same as Japan and Australia. That’s evidence of a very high degree of entrepreneurialism. Admirable.

The other interesting thing about South African institutions at the moment is the attention being paid to curriculum. As I noted previously, South Africa is plagued by drop-outs; only about 50% of starters complete their studies. The culprit, by general agreement, is under-preparedness of students; there is an articulation gap between secondary and post-secondary (which makes initial transitions difficult) and curricula in many subjects contain transition points that takes for granted certain knowledge and abilities that all students may not have.

(Interestingly, while there are wide gaps in primary and secondary schooling available to Africans and whites, the dropout problem is only partly related to this. Though there are differences in completion rates by “population group” [the preferred way to say “race” in South Africa] they actually aren’t that wide: 6-year graduation rates for Africans are 47%, compared to 59% for whites. Compare that to the US, where the rates are 40% for Blacks and 62% for whites.)

So, your country’s system has an articulation problem, a transition problem and – to top it off – worries about how well current education is preparing students for the future labour market. What do you do? Well, the current preferred solution to this problem (outlined in this document) is to lengthen periods of study: that is, to move from a system of mostly three-year degrees to a system of mostly four-year degrees. And this isn’t simply a matter of adding a base foundation year – what’s being contemplated is a wholesale re-writing of curricula from the ground-up. In some ways, it’s a more daunting task than the Bologna curriculum re-write, which often involved little more than slicing five-year degrees into a three-year Bachelor’s degree, and a two-year Master’s.

It’s not entirely clear whether this will happen – cost implications are significant, and there isn’t a lot of money in the kitty in Pretoria. But having gone through our own debate about degree-lengths a few years ago, it’s refreshing to see a discussion driven by desired learning outcomes and curriculum analysis rather than vigorous hand-waving from politicians.

South African universities have taken extraordinary measures to close the funding gap; if they were able to take similarly bold measures to tackle the attainment gap, the payoff would be profound.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post