One of the best – and yet perhaps most confusing – ways to look at the current state of today’s students is to look at the Canadian version of the National College Health Assessment (NCHA) survey, which is done every three years. I want to take you through a quick comparison of the 2013 and 2019 surveys (each of which were taken by tens of thousands of Canadian students, so it’s a good sample), because I think there is a complicated but important story going on with students. It is one which illustrates some of the challenges occurring in student affairs these days, including how to interpret data around unwanted sexual contact (which I discuss below).

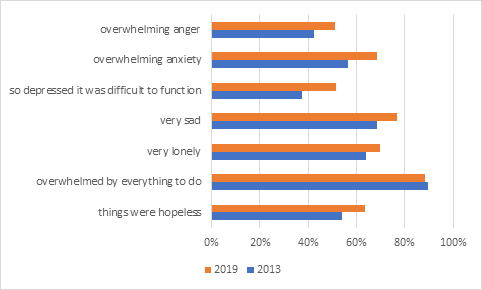

So, let’s start with what I think is the good news: which is that student consumption of cigarettes and alcohol is down (substantially in the latter case).

Figure 1: Student Use of Cigarettes and Alcohol over Past Month, 2013 and 2019

Marijuana use is up – presumably a matter of legalization – but use of other drugs is equal or lower than what it was six years ago. Among other things which seem to be about the same: reports of being in emotionally abusive relationships are similar (11% in 2019, 10% in 2013), having multiple sexual partners (22% vs. 21%), purging or taking laxatives to lose weight (4% vs. 3%), taking diet pills to lose weight (2% vs. 3%).

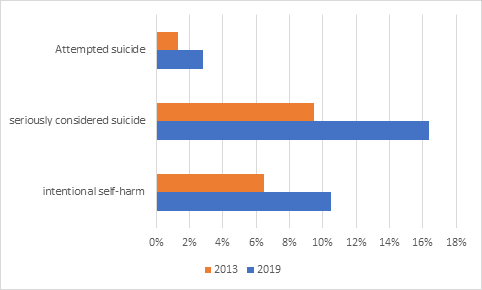

Now where it starts to get concerning is when we start to get into areas of mental health. The NCHA asks students about whether they had experienced certain feelings over the past year. On virtually every measure except “feeling overwhelmed” (which was already well over 80%), the number of students responding in the affirmative grew by 5-10 percentage points across the board.

Figure 2: Students reporting following feelings over past 12 months

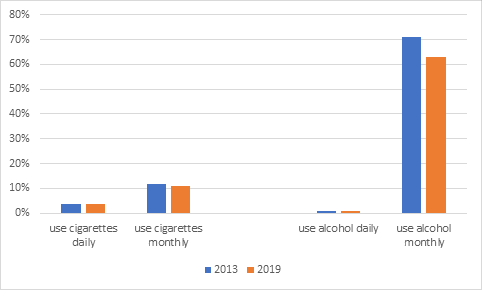

The NCHA survey then goes on to ask a number of questions with respect to whether, in the past 12 months, students had either been diagnosed or treated for a variety of mental health issues. Pretty much across the board, what we see is a doubling of students answering in the affirmative, in a mere six years. Now what’s interesting here (to me at least) is that while the growth of mental health issues in higher education are usually described as attributed to changes in various external factors (stress from higher tuition, stress from a tougher labour market, greater pressure to get into grad school, what have you), not all of these mental health issues are usually seen as stress related (e.g, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder).

Figure 3: Students reporting Treatment for/Diagnosis of Various Conditions, past 12 Months

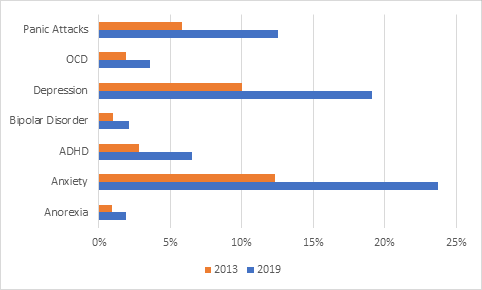

Now, that said, even if you’re tempted just to dismiss this as a case of medicalization of mental states, it’s harder to dismiss other numbers, where the survey is actually documenting acts rather than mental states. The percentage of students who report committing acts of intentional self-harm over the past twelve months rose from 6 to 10 percentage points; the percentage reporting an attempt at suicide rises from 1% to 3%.

Figure 4: Students reporting on issues of self-harm and suicide, past 12 Months

Okay, so given all these statistics, why hasn’t there been an almighty hue and cry? This data’s been out for about a year now, and if everybody in higher education took this data at face value, you’d think there would be an enormous effort to confront what looks like an alarming deterioration in students’ mental health.

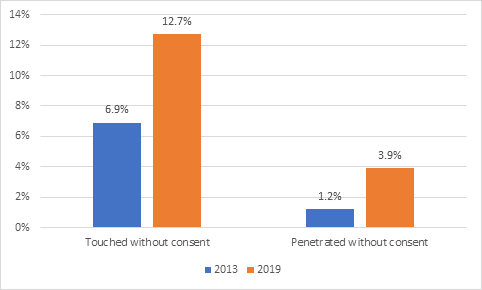

The data on unwanted sexual contact provides a clue for answering this question. In figure five we see a doubling or even tripling of students reporting this kind of event, which raises many questions. If there had been a tripling of sexual assault, I am reasonably confident this would have come to public attention about it through other sources, such as through campus sexual assault networks. That’s not to say we should question the accuracy of the 2019 data: but on the whole, if you ask me whether sexual assault has actually tripled in the last six years or whether it has always been this high (or higher) and students are now, in the era of #metoo, more likely to report it, my guess is that it’s the latter.

Figure 5: Students reporting on issues of sexual assault, past 12 Months

And this is the whole challenge with interpreting these kinds of surveys, particularly when you are comparing data over time. It’s not just that self-reporting of some types of events is subjective; it’s that social understanding of certain terms changes over time, as does the perceived stigma of reporting things like mental health issues. So, it’s very difficult to tell whether or not there is a deterioration of student mental health, or whether certain emotional conditions are more likely to be described that way and, in turn, medicalized. However, the data on actual acts is troubling and should be carefully monitored. All you can really do is note the change in the way people describe what’s going in their lives and act accordingly and compassionately.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

What the powers-that-be understand to be “accordingly” (not to mention compassionately) is also socially understood and changes over time. The data on “mental health issues” in faculty, staff and administrators — and others employed in higher education — should therefore also be carefully monitored and discussed. Arguably the stigma is greater here, not to mention the risks from being associated with (what are still generally regarded as) disordered and disorderly behaviour and states — this despite the fact that there are good data suggesting that students benefit greatly from role models on campus who themselves are open about their own mental health struggles and lived realities of disability more broadly.

There are likely acts associated with the mental states as well — some highly concerning, at least as much as suicidal ideation (which isn’t an act) and self-harm. Indeed, in my own subjective view as a person with a neurodevelopmental and a mental health disability, there is no real divide between acts vs. mental states. Viewing them as separate is certainly valid, but also socially understood, constructed, and controlled.