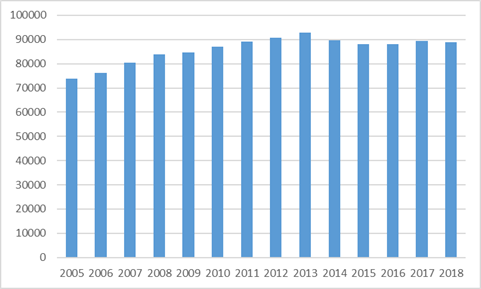

It’s always good, once in awhile, to check up on application statistics, just to check up on demand for education. Ontario, thank God, has a system that allows you to look at applications system-wide. A few years ago, everyone was panicking about falling application numbers because of a five percent fall in 2013-2015, mostly caused by a significant fall in the number of 18 year-olds.

So how have things been since then? Well, it turns out that application numbers have stabilized. In fact, given that the number of 18 year-olds has continued to decline slightly, this stabilization represents a slight increase in the rate of application.

Figure 1: Total Applications from Secondary, Ontario Universities, 2005-2018

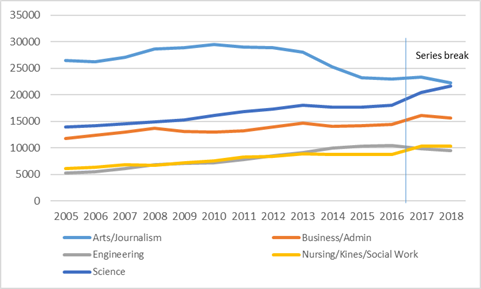

One thing that used to be great about OUAC statistics is that they had useful time series on applications by field of study. This really helped one understand what students and their parents were thinking about the labour market, (for instance about the trend away from Arts, such as the one here).

Unfortunately, OUAC’s member institutions decided that the old way of categorizing student applications no longer served their needs and so they came up with a new one. Unfortunately, not only did neglect to provide a decent cross-walk that would allow one to put the new categories inside the old ones to maintain some kind of continuity over time, but there were no agreed-upon standards for how to classify existing programs. It’s almost like they are taking lessons from Statscan on how to kill time-series data.

It’s mostly possible to develop a concordance across the two (which I did – concordance available on request), but there’s one major anomaly, namely the new “Computer/Info Science” with about 4000 students who were formerly included in both Science and Engineering, though in what proportions I cannot say. Allocating them either to Science or Engineering causes one of the two time-series to show a sudden and unnatural spike: for no particularly good reason I chose to fully allocate to this group to Science, which likely accounts for the small shifts in Science (upwards) and Engineering (downwards) for 2017 which you see below in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Applications to Ontario Universities by Field of Study, 2005-2018

What’s interesting here is that while in 2005, there were 26,500 applications to Arts, Social Science, Communications and Journalism, and only 19,120 applications to Science and Engineering combined. Fast forward to 2018 and it’s a completely different story: 22,214 applications in the Arts and 31,232 to Science and Engineering. In terms of proportions of overall applications, their positions have nearly reversed: from 36-26 in favour of Arts in 2005 to 35-25 in favour of STEM in 2018.

The government should pay attention to this shift. First of all, it shows that student preferences do change over time in response to perceived changes in the labour market (I say perceived because there very little evidence to suggest that outcomes for Science grads are much different than those from Social Sciences). But more importantly, Science and Engineering have significantly more expensive programs to provide than Arts. For universities to respond to this kind of shift in demand means a somewhat more expensive university to operate. And either government or students will need to shell out for it, or we have to keep turning away large numbers of students who wish to enter STEM.

I wonder which it will be.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

What is the cause and effect relationship here, Alex? Do the student applications arrive as a result of universities’ marketing strategies and decisions on emphasis, as captured in SMAs, for example, maybe even due to external pressure (governmental or the lure of higher tuition revenue for professional engineering programs)? Or do the universities adjust their programs and marketing in response to shifts in students’ interests, perhaps somehow measured in terms of application trends? I think it is fuzzy to suggest that students’ interests are changing based on some perception of the job market, while not acknowledging the choices made and money spent by universities in marketing and developing certain programs over others.

I can tell you based on quite a few years of primary research that students’ decisions on field of study come long before they get into any kind of contact with universities.