Late last week the Business Higher Education Roundtable published the results of a survey of its members (big Canadian businesses) on the issue of skills. The results were…intriguing.

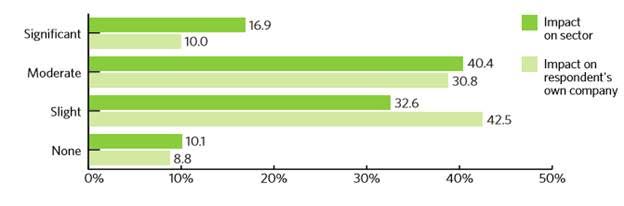

Let’s start with the classic question: are there skills shortages? Here’s what respondents said.

Figure 1: To What Degree are Skill Shortages an Issue for your Sector/Company?

Yes, there are skills shortages, but a) not many think they are that significant, and big business thinks they’re better insulated than other companies in their sector. But compared to when the Canadian Council of CEO’s asked a similar (but ever so-slightly differently worded) question four years ago, the answers seem to be that skills shortages seem to have eased.

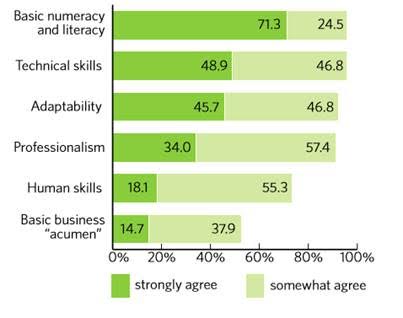

Next, let’s look at what Canadian business thinks about the skills of new graduates. As you can see in the chart below, they are actually pretty bullish on graduates’ technical skills. What they’re less happy about are “human skills” (which I assume is some variant on “soft skills”/critical thinking) and “business acumen” (which I assume is code for “knowing how to act in the workplace in a way that benefits the company”).

Figure 2: Do New Graduates Have These Skills?

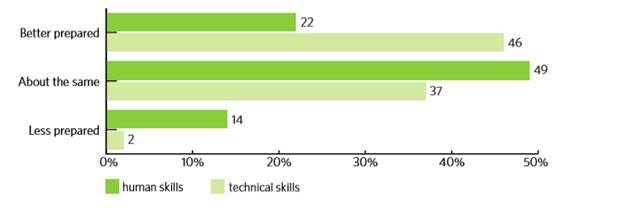

In fact, not only do businesses think new grads are (mostly) doing OK on skills, they also think the quality of graduates are better than they were five years ago (I really like this question, thanks Val/Isabelle for including it in this survey).

Figure 3: How Prepared Are New Graduates Compared to Five Years Ago

So, graduates are way better prepared technically than they used to be, somewhat better prepared on “human skills”, and overall are seen to perform better at the former than the latter. Now, as it turns out, this still greatly matters to business because when asked what skills businesses look for when making entry-level hires, the answers are i) collaboration/teamwork/interpersonal skills, ii) communication skills, iii) problem-solving skills, iv) analytical capabilities and v) resiliency (intriguingly, industry-specific knowledge apparently becomes more important when looking at mid-level hires).

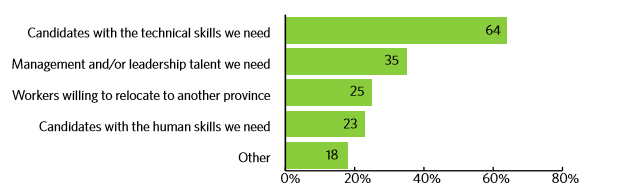

So, obviously, when it comes to actual skills in short supply, it must be those human skills and not the technical ones, right?

Figure 4: Types of Employees in Short Supply

OK, wait, what?

So…business thinks technical skills are good and getting better, and human skills less so. They say technical skills are not the main thing they are looking for when hiring. But when it comes to asking about where the shortages are, the answer is: technical skills. The easy conclusion to come to here is: business has no idea what it is talking about (or at least, C-suite and the HR department actually don’t talk to each other when it comes to hiring priorities).

There is a slightly – but only slightly – more charitable reading though. It could be that business is happy with the talent pool available for most of the jobs they need to fill, but they lack a few key “superstars” who can drive technological change. Or something. In any case, there is an obvious remedy for this kind of thing which is to, you know, actually pay people more for in-demand skills (side note: recent economic research on the effects of monopsony power on local labour markets may provide clues why Canada’s relatively sheltered markets result in lower market wages than those necessary to attract talent) or do more training themselves.

In any case, the point I want to make here is that apart from that last graph, the message business is sending is the same message we say from the Royal Bank a couple of weeks ago, the same message Joseph Aoun has in his book Robot-Proof: Higher Education in the Age of Artificial Intelligence and basically the same one I had when I talked last year about “Nordstrom philologists”; the real, central skills needs of employers mostly have nothing to do with field of study. It’s not STEM; it’s skills, some of which are computational/analytical in nature, and some of which are about listening, communicating and working in teams.

Maybe STEM gives you some of that, maybe humanities gives you some of that – I tend to think both could, given the right conditions and the right curriculum design. But the point is: we’re continue to inch closer to a consensus on the kinds of skills needed to thrive in today’s economy. The question is how well institutions (particularly universities) are listening and how well they can integrate these skills into their curricula.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Interesting.

It could be that while the human skills are the most important, they’re also well-supplied by the talent pool, so what differentiates applicants is not whether they can manage the human skills part – they can – but whether they can also manage the technical skills part – and in some cases, they can’t.

This would actually make sense to me. Technical skills are the most transient. Being technically qualified today doesn’t mean you’re technically qualified five years from now (or in some disciplines, even a couple years from now). So if your program isn’t 100% cutting edge, you’re going to start out a bit behind the curve.

*But* if they have good human skills, they should be able to teach themselves (that’s what they’ll need to do in 2-5 years anyways). And that’s how we can have a skills shortage even though we’re doing a good job preparing people with the skills they need.

Anyhow, good discussion.