If there is one thing that drives me to despair about Canadian universities these days, it is how poor many federal government relations (GR) strategies are. I can boil the issues down to three specific aspects.

Too many cooks. 30 years ago, I am fairly sure no university in Canada had a permanent independent GR presence in Ottawa (apart from the two schools located there). Now there are a couple of dozen who do. Much of what they are trying to accomplish is to whip up some enthusiasm for some new project on campus – usually some kind of scientific infrastructure. This is mostly a waste of time. There were a couple of years under Harper when the Prime Minister’s Office indulged this kind of thing (because there were few things the Harper government believed in so much as the ability of the PMO to pick winning research), but that hasn’t been the case for many years now.

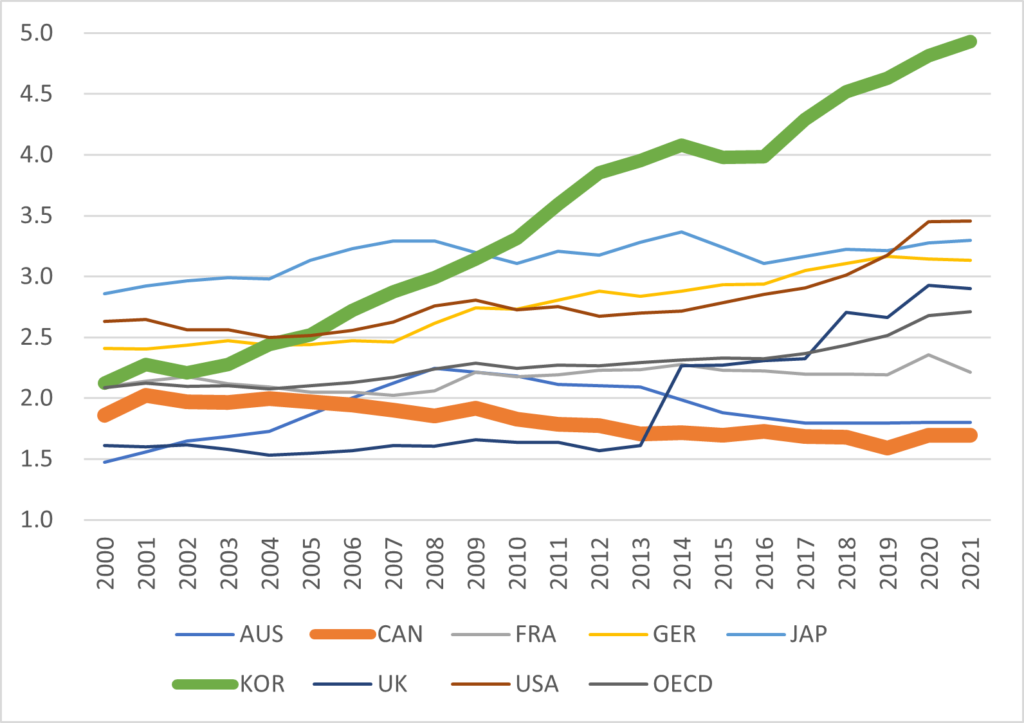

Nobody cares about Korea. There is nothing Universities Canada and the U-15 love more than a good graph like the one below showing how bad Canada is at Research and Development in comparison to, say Korea, and waving it around Ottawa yelling: “Look! Korea!”

Figure 1: The “Korea is Magic!” Graph

Nobody in Ottawa cares about this comparison, for three reasons. One, nearly all that extra Korean R&D money is being spent by the private sector; it’s not really an argument for more government spending. Two, we have no idea if that huge extra effort is producing real gains for Korea. To the extent that R&D changes economic fortunes, it takes awhile for results to show and current Korean prosperity is more likely to be a result of policies enacted 20 years ago, when its R&D expenditures were average. And three, more generally, just because country X is doing something does not necessarily mean Canada doing is a good idea. You need to make the case in a detailed way. Otherwise, it’s just an “all-my-friends-are-jumping-off-a-bridge” argument.

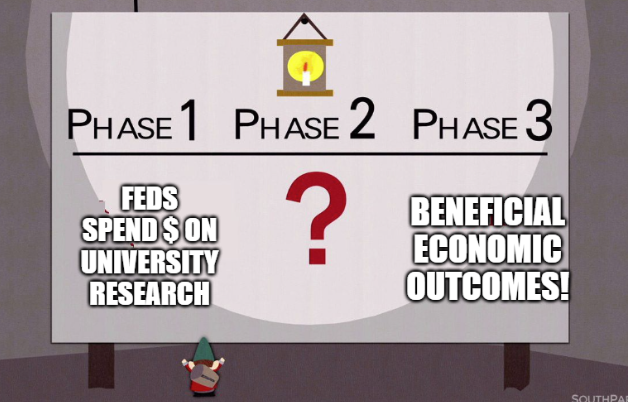

Nobody Believes the Economic Growth Story. Since about 1996, universities have been telling the same story to the government. It is very much an Underpants Gnomes story.

Figure 2: The Unvarying Yet Unconvincing University Argument on Basic Research

The Feds believed this story for about a dozen years but have not done so since around the time of the 2008 financial crisis. Yet for the past 15 years, the sector has been pushing the exact same story, at best altering the wording of “beneficial economic outcomes” to suit the Ottawa buzzword du jour (“innovation” under Harper, “middle class jobs” under Trudeau and who knows, maybe “powerful paycheques” under a future Poilievre government) AND STILL NO ONE BELIEVES IT. We can argue a bit about why that’s the case (my theory on this is back here), but for Universities Canada and the U15 to keep pushing the same story year after year in the face of repeated failure seems much akin to that misattributed Einstein quote about the definition of insanity.

There are solutions to these problems. But they involve a massive shake-up of the way the entire sector does GR. I propose six things.

- Most universities should close their Ottawa operations. This one will be extremely hard for most institutions to accept because they and their boards will see it as akin to unilateral disarmament. But it’s arguably the most important: individual universities running around (futilely) pressing their own schemes gives official Ottawa the impression that the sector is disunited, all fighting for their own piece of the pie. Every single Presidential meeting in Ottawa which is pressing for anything other than common themes is not just a waste of time, it’s actively making things worse.

- STOP TELLING UNDERPANTS GNOMES STORIES. This really shouldn’t require elaboration.

- Less self-centered narratives. This is more for faculty-groups and researchers than it is for universities: the plea for more money can’t be about “but I have to keep my lab open”/”my grad students need more money”/whatever. Those things are all important, but fundamentally they sound self-centered to politicians, who then ignore it. The arguments must focus on wider benefits, and framed in terms of “what kind of Canada do we want to live in”, not “how many graduate scholarships should we have”?

- Build coalitions. First, within the university sector, institutions need to pick a common line and stick to it. This shouldn’t be difficult, but in fact it was only last month that the U-15 got its act together and developed a “Coalition for Canadian Research”. The letter is still just recycling the same old arguments, but it’s progress, nonetheless.

- Build broader coalitions. You know what would make the story more powerful? If itincludescolleges. Find a way to include community colleges and applied research in the narrative, and not just as some kind of annoying afterthought.

- Keep going: even broader coalitions. But to really change minds in Ottawa, coalition-building will have to extend well beyond the sector to include many people who want Canada to have a broad culture of inclusive growth, not just people who want more research infrastructure. Here, I will re-iterate what I said on this subject a couple of years ago: It means talking to the business community (the forward-looking bits of it, anyway). It means talking to the NGOs and local community groups, to include them in a coalition which can make cities cheaper (preferably by massive investments in housing), more innovative, and more inclusive. And it means bringing Indigenous nations and smaller communities into the discussion, too, because right now the rural communities agenda is utterly divorced from any discussion of skills and education and that’s terribly wrong and dangerous. Better strategies for delivering post-secondary education in smaller communities must be part of a long-term growth agenda as well.

I’m not saying any of this will be easy. Keeping university coalitions together is very much an exercise in herding cats, which is not a great foundation upon which to try to build even larger coalitions. But it simply must be done. I am pretty sure universities have already lost their shot at a research budget increase for the 2024 budget cycle, bar perhaps some movement on graduate scholarships. But there is still hope for 2025, provided a new message and new tactics are adopted over the next couple of months.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Really interested in Build broader coalitions with colleges. Any suggestions?

Point 3 will infuriate a lot of readers, but it is important. Convincing Ottawa that graduate students and postdocs should earn a living wage means convincing Ottawa that it is in the national interest to have graduate students and postdocs doing their research and training on a full-time funded basis (and not simply a budgetary rounding error funded mostly out of inertia).

As usual, witty and worth reading.

I wonder about your simultaneous dismissal of the underwear gnomes argument and claim that you want to discuss “What kind of Canada do we want to live in?” The underwear gnomes argument is, at least implicitly, a claim that we want a Canada that supports basic research and that will implicitly be one richer, more innovative, more just (insert current buzz-word here). So it seems to answer the question.

It’s certainly better than the cause-and-effect argument of Soviet-style central planning, by which we’ll achieve a (say) more innovative Canada by ignoring basic research in favour of seminars on innovation, a more just Canada by ignoring literature in favour of lectures on social justice, and so forth.

What we need isn’t just a broader argument, beyond the latest lab or whatever, but a broader argument beyond the goods and services that universities might provide, to why learning is a good in itself.

For building coalitions with colleges…

Might colleges provide university students with access to lab spaces?

This would give university students access to learning opportunities with lab equipment that is often more sophisticated or modern at colleges.

(Though one difficulty might be the fact that lab spaces are hyper-utilized in colleges and it is difficult to find labs that are not 100% booked for college student use.)

And might universities provide colleges with the opportunity to access larger lecture spaces?

College campuses were often designed for small-group teaching with smaller class sizes.

This means that there are fewer larger lecture spaces available on college campuses, making it difficult for colleges to expand more pen-and-paper focused course and program offerings.