To One Yonge Street, and the offices of the redoubtable Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario (HEQCO), who yesterday released a small publication with the unassuming name, The Productivity of the Ontario Public Postsecondary. The title may be a little on the soporific side, but the contents are anything but.

There are some real gems in here. Did you know that 39% of all granting council funding went to Quebec? OK, the grants on average are somewhat smaller than they are in Ontario, but that’s still an incredible number. It’s not as though, on average, their publication records are better than anyone else’s (they’re not – see Table 7, which we, here at HESA, contributed to the report). By what quirk of the funding council system does this happen? What’s the secret to their success? Inquiring minds want to know if this is replicable elsewhere?

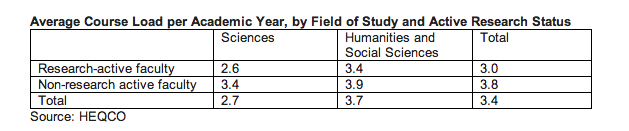

But for my money, the really explosive section is Table 9, which takes data from four collaborating institutions (Guelph, Queen’s, Laurier, and York) in order to look at staff workloads. Specifically, workloads were analyzed according to whether a professor had any “research output” (defined – rather generously, I think – as having held any external grant, or had a publication in the 2010-2011 academic year). Here’s what they found:

A couple of points here: First, the comparison for science isn’t especially interesting since there are almost no non-research-active faculty there (over 80% of them hold an NSERC grant at any given time). In the SSHRC fields it’s a different story – it’s closer to 50-50. But, apparently, the ones who are research-active are not bunking off teaching to do their research; in fact, they only teach a half-course less per year, on average, than those who are non-research-active. Perhaps the better question here is, “what exactly are all those non-research-active profs doing with their time”?

Obviously, there are some possible ways this result could be innocuous. It could be that the non-research-active profs spend more time devoted to service, or that the line between research-active and non-research-active isn’t especially clear-cut in humanities and social sciences (if publication is mostly in the form of books, it’s easy to go a year, or more, without a new one). You’d have to do a lot more digging before jumping to any definitive conclusions.

But just the fact that HEQCO got four universities to go even this far with their data is a big deal. It’s the biggest move anyone’s made so far to start engaging publicly on the issue of faculty productivity. So kudos to HEQCO and the four institutions that participated. The sector is going to need a lot more of this if it’s going to adjust to the new fiscal reality.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

It is not clear whether, for the four universities included in the pilot workload study, only full-time regular faculty were included. Queen’s has Adjuncts (and they hold rank) whose duties are for the most part teaching-only and whose appointments are part-time – they are not paid to do anything else.

The real question here — and one not answered by the report — is why do those in the humanities and social sciences have course loads that are so much higher than those in the sciences? About 0.8 more courses per year among active researchers according to the data in the table above.