Last Week, Royal Bank produced a study with the brash headline “Financial Returns After a Post-Secondary Education Have Diminished.” Within the limited terms of the limited methodology of the first half of the mini-paper, the headline is not entirely incorrect. But man, this is a disappointing piece of analysis from an organization with pretensions to thought leadership.

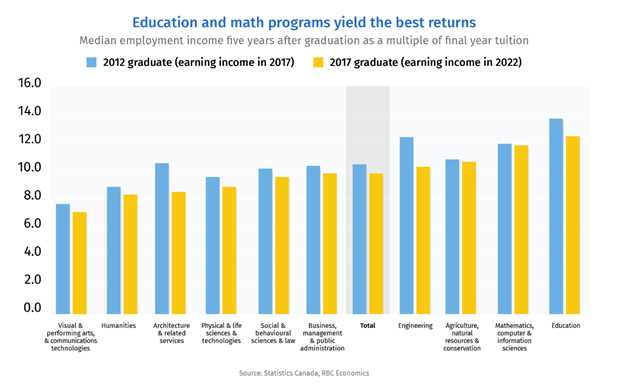

So, what does this paper say? Basically, part 1 of the paper takes four data points for university (NOT all of post-secondary—strike one for the headline writers) graduates: Tuition fees in 2012 and 2017, and median salaries of graduates five years out for graduates of the classes of 2012 and 2017. Then they create ratios for the two graduating classes: what they made five years out divided by what they paid in their final year of school. This they call “financial returns,” which of course they aren’t in any strict sense: at best, it’s a very rough-and-ready back-of-the-envelope calculation.

And what did this analysis find? Well, you have to squint pretty hard at a chart in order to figure out the overall numbers (because the actual figures are not provided), but apparently that ratio for university graduates (again, not post-secondary graduates) has fallen from about 10.3 to 9.8.

I mean, I guess you could spin that into a big headline finding but it seems like a pretty feeble result to me. Feeble for a couple of reasons, some of which are right there in the report if you bother to keep scrolling down.

I mean first of all, this whole thing is based on the assumption that “returns” at a single point in time five years out of school is an appropriate proxy for total returns. This is pretty iffy, if you ask me. A real comparison of returns would look at total tuition paid (not one year), and include foregone earnings, and take into account lifetime earnings, not those from a single year. So, methodologically, this is pretty weak, although I completely get that they are doing it because Canadian governments don’t collect and disseminate anything like the data they should which means that quick-and-dirty comparisons like this is about all we can reasonably expect. But still, making a big deal out of a drop from a multiple of 10.3 to 9.8 for a single year of earnings…good Lord, that is still an EXTRAORDINARY RETURN. What is there, really, to complain about here?

Second of all, these returns are still very good compared to any other form of education. The data about annual earnings by education level are pretty striking: Canadians with college and trades (apprenticeship) credentials earn 50% more than those a simple high school degree while Canadians with a university education earn 100% more. We shouldn’t make too much of this because the analysis is pretty crude and these aren’t returns in any strict sense, but again, come on this remains evidence that post-secondary education is probably still an excellent deal.

Third is the fact that the denominator here is sticker price tuition. It completely ignores any student financial assistance which reduced the cost—and over the years in question, the rise in student grants was substantial, thanks to the expansion of both the Canada and Ontario student aid programs. I think there is strong evidence that the magnitude of these increases was sufficiently large to offset any increases in the sticker price. Thus, since the study did not find that graduate incomes are decreasing, but rather that they were increasing less quickly than sticker prices, including student aid would reverse the finding and find that returns are increasing.

(Royal Bank is hardly the only organization to completely ignore net price in its analyses of postsecondary returns or postsecondary affordability—they have plenty of company because Canadians tend not to think in more than one dimension about that stuff. But man, it’s annoying)

Fourth, contra the headline paragraphs, and as I keep pointing out, tuition has not been rising for the past few years. In fact, since 2019 average tuition in Canda is down by x% after inflation, thanks (?) mainly to policy changes in Ontario. And, again, if you scroll down on the paper, the authors themselves acknowledge this. But while the authors know that the main factor “eroding” the value of higher education has been going in reverse for the past five years, their choice of a five-year time frame to measure returns means they cannot take into account something they know to be true in coming up with their feeble headline about declining returns.

Anyways, I am conscious that I may be ranting at least as much about the headline writer as I am about the piece of research itself. It’s an irresponsible framing, rather than irresponsible research. It is the kind of thing the sector itself needs to push back on (or you know, produce its own research on once in awhile).

But still, Royal Bank could have done much better here.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Excellent analysis and very justified rant. I have to say, though, that it is still very reassuring that the findings indicate a very good return on investment across the board of academic disciplines (although the weakness of the analysis implies that the results need to be considered with caution).

I am pleasantly surprised and encouraged by the results for Education. Education is one of the options that I mention to every student who asks (no, I’m not in a Faculty of Education). Where else, except for Nursing, do you practically have a lifetime job guarantee? And you can choose to live in any jurisdiction in North America if you specialize in any of the many teaching areas of high demand.

And yet, out of the many students who have asked for my advice over so many years, I can only recall a few who went that route.

The job has such a bad reputation that even lifelong job guarantees and defined benefit plans (where do you get that anymore?) cannot convince recent high-school graduates to pursue that career. Even kids who come from very rural schools have rather disturbing and discouraging stories to tell.

It’s bad for everyone. Our first-year courses are now mostly reviewing high-school material because teachers give in to the general expectation that K-12 is age 5-18 daycare. I know teachers who will never give up, but I also know some who caved.