So, although it wasn’t widely noticed at the time, one really excellent piece of policy came out of the crap-fest that was the Quebec Education Summit, a couple of weeks ago; it’s a policy that deserves a great deal of wider study and emulation. For the first time in Canadian history, a government managed to get rid of a crappy tax credit, and use it to improve targeted, needs-based subsidies.

Here’s what happened. The PQ, during its naked bid to win the affections of students in the run-up to the 2012 election, promised students that not only would they rescind the tuition hike imposed by the Liberal government, but they would also uphold the generous new student aid package the Liberals offered as a sweetener. But of course, that meant spending double – so they needed a new form of revenue, at a time when the provincial budget was under pressure.

Enter the tax credits.

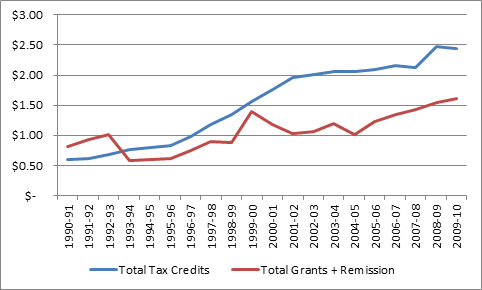

Now, if you’ve at all been following student aid over the last decade, you’ll know that Canada went tax-credit crazy around about 1998. Mostly, it was a federal thing – a way for the feds to get money to parents for education, without the tedious mucking about of negotiating deals with provinces. But some provinces went along for the ride, too. In any case, the value of education tax credits rapidly surpassed the combined value of grants and loan remission.

Total Value of Education Tax Credits vs. Grants & Remission, Canada, 1990-91 to 2009-10, in Billions of 2010 Dollars

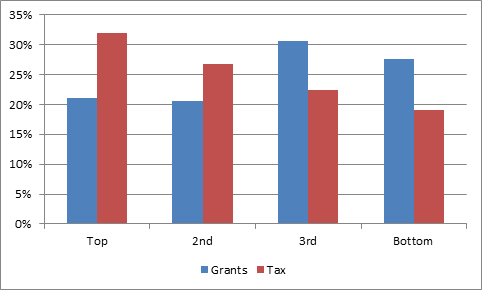

Why does this matter? Because tax credits are given out without regard to income or need. And since kids from better-off backgrounds are more likely to go to PSE, tax credit expenditure, on aggregate, mostly ends up in the hands of people from the top 2 income quartiles. Grants, on the other hand, are more likely to end up in the hands of people from the bottom 2 quartiles (the reason they don’t end up there entirely is because a lot kids from richer backgrounds get quite a lot of aid once they turn 22, and become “independent” students).

Distribution of Benefits by Income Quartile, for Selected Student Assistance Measures

Source: Usher, A (2004) Who Gets What? The Distribution of Government Subsidies for Postsecondary Education in Canada. Toronto: Educational Policy Institute.

Now, over the past decade, a number of groups have recommended replacing tax credits with grants of some kind – even the CFS, who bizarrely denounce tax credits as regressive, even though they have EXACTLY the same re-distributive consequences as the tuition cuts which the CFS backs so fervently (consistency is not their strong suit). Almost everyone – bar Michael Ignatieff – ignored these calls, essentially on the grounds that Canadians wouldn’t stand for what would amount to a tax hike.

Well, now the PQ has proved them wrong. A government has converted a regressive universal program into a targeted progressive one, to no opposition whatsoever, even in a highly-taxed province. Policy-makers in the rest of the country should take note.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Thanks for the really interesting piece. I’m just wondering what you think of the argument that universal transfers, although more expensive, are important for preserving political support for progressive policies. In this case, although much of the transfer winds up in the hands of those who don’t need it, that gets middle and upper-income buy-in. Targeted, means-tested transfers might be more efficient in redistribution, but don’t have a lot of voting constituents, and can more easily be reduced.

Anyway, that’s one line of thought. Any merit in this case?