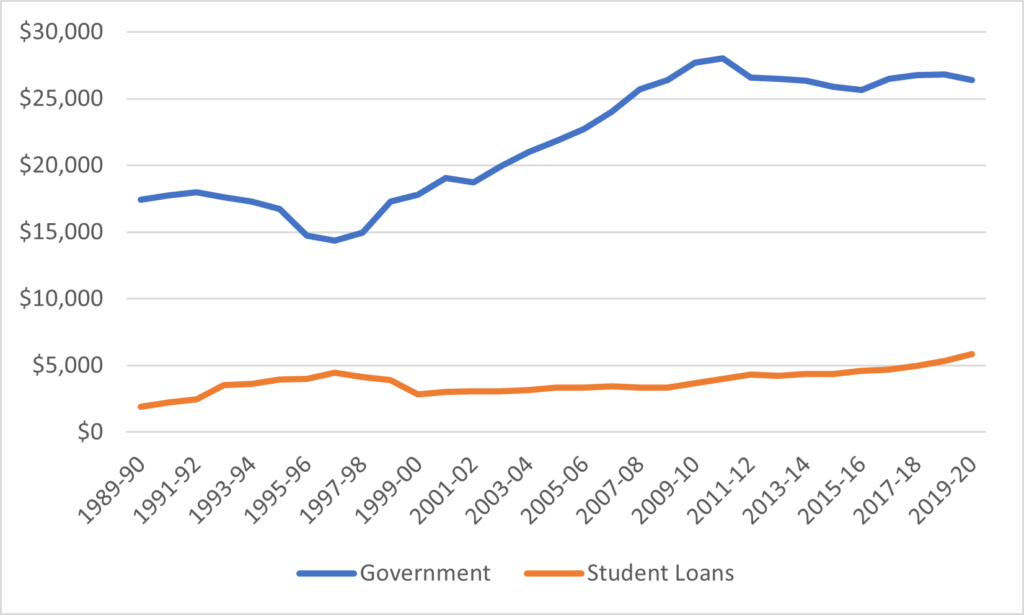

Over Xmas, someone asked me on Twitter whether student loans were replacing direct government support as a main source of public assistance. I answered, no, direct government support either from the feds (mainly through research and infrastructure) or the provinces (operating grants), are worth about five times more that the annual value of student loans. To wit, Figure 1.

Figure 1: Annual Student Loan Disbursements vs. Total Government Transfers to Post-Secondary Institutions, Canada, 1989-90 to 2019-20, in constant $2019 Millions

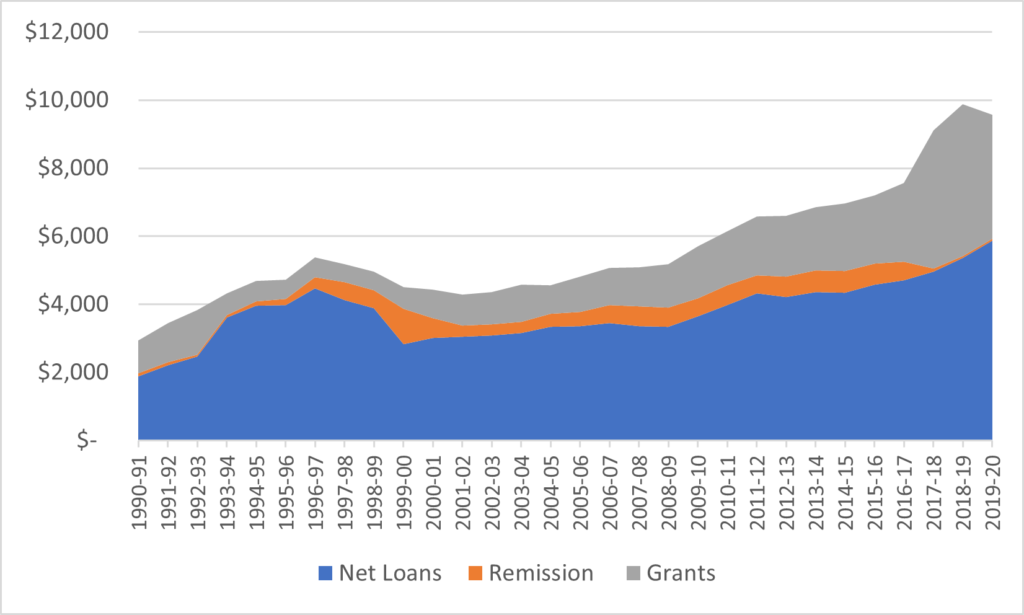

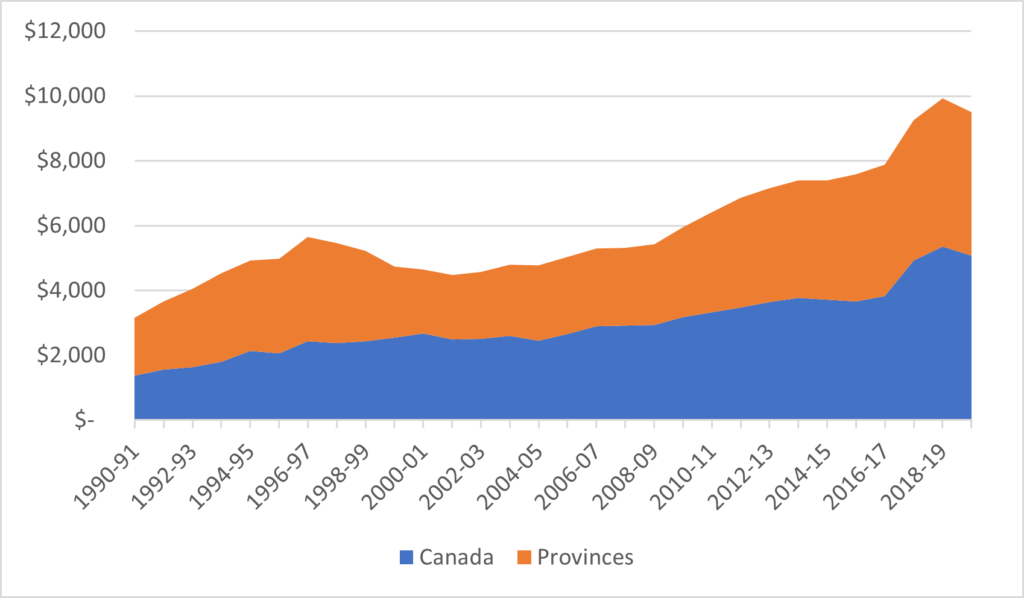

The following exchange made me realize how little is generally understood about the evolution of student aid in Canada. That’s because a) student aid is split between the federal and provincial levels, b) most provinces are really bad about releasing data on student aid unless you FOIP them and c) literally no one other than me bothers to keep track of this stuff. Anyways, to start, let’s just look at the evolution of repayable assistance by type: loan, grant and loan remission, since 1990 (Figure 2), and by source, federal or provincial (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Annual Student Aid Disbursements by Type, Canada, 1990-91 to 2019-20, in constant $2019 Millions

Figure 3: Annual Student Aid Disbursements by Source, Canada, 1990-91 to 2019-20, in constant $2019 Millions

Now, let me explain what’s going on in these two graphs.

In the early 1990s, Canadian student aid programs were under a lot of pressure. The way loans worked back then was that the Canada Student Loans Program took care of the first $105/week, and provinces then topped that off with assistance of their own with about $50-$60/month, usually in the form of grants. The exceptions were Ontario, where the provincial grant was given out before the federal grants, and Quebec, which had opted out of the Canada Student Loans Program and ran its own separate system. The problem was that these programs hadn’t changed for a decade or so, and inflation had eroded the purchasing power of this aid by about a third. Moreover, it was becoming clear that the 1990s were going to be a decade of fairly substantial tuition increases. So, what to do?

During the very brief Kim Campbell era, the feds hit on a solution. They would raise their limit from $105 to $165/week, but they would only accept responsibility for 60% of all need: the rest – theoretically $110/week – would be up to the provinces. This created a huge headache for the provinces: not only would their contribution have to nearly double, but they would have to meet need from the very first dollar, instead of just those with over $110 per week. It effectively doubled provincial financial commitments (see the big increase in the orange area in Figure 3). So, the provinces did what you’d expect: they tried to cut their costs by turning their grant programs into loan programs (see Figure 3). Some provinces really got into it: not only did they meet the new $110/week limit, but also allowed even higher borrowing for students with high need, such as students with dependents. But basically, the borrowing maxima across the country (excluding Quebec) went from $3570/year ($105/week * 34 weeks per year) to $9350/year ($275/week * 34 weeks). Good for liquidity – students had more money to spend, but bad from a debt point of view.

You can see the mountain of new borrowing in the mid-90s in Figure 2. But you’ll also see that it subsequently got reined in. How? There were a few factors: tightening eligibility rules, loan limits preventing students from borrowing more, governments distributing more grant aid, and students could work more due to improving economic conditions. As a result of this, net lending – that is, loans minus remission – did not reach its 1996-97 heights again until 2015. All those stories about “skyrocketing debt” you’ve heard over the past 25 years? Simply not true.

From 1999-2000 – the year the Canada Millennium Scholarship was created – until 2015, the policy environment was pretty quiet. Every year, the federal government were disbursing over 50% of all student aid dollars – very different from the mid-90s – and both loans and grants drifted slowly. But 2016 that was the year student aid started a new big run-up. The federal government killed the education tax credit, and stuck it into grants. The Ontario government killed loan remission, the tuition tax credit *and* the education tax credit and dumped it all into grants. And the feds began relaxing rules on need assessment (mainly by ending clawbacks on earned income, giving students more income in the short run but running up student debt. This combination briefly pushed total of disbursements to just under $10 billion, with almost half coming in the form of grants. And then Doug Ford came along, and – because roughly half of all student aid dollars in Canada are disbursed in Ontario – by slashing OSAP like it was in a cheap horror movie, singlehandedly reduced national grant spending by $800 million and boosted loans by $500 million.

So, the long-view of Canadian student aid is basically this. Over the very long run, Canadian governments seem to add about $200 million in real terms every year to student aid. But there have been two big “convulsions” – one in the 90s where student aid rose and fell mainly due to changes in loans programs, and one in the late teens when it rose and fell mainly due to changes in grant programs. This particular convulsion still has a ways to go: there were big increases in federal grant spending during COVID, which may or may not expire in 2023; the Ford government may go and its policies reversed; loan limits may rise again (they were increased to – effectively – $350/week in 2006 or so, but have not moved since and are probably due for a hike). The list goes on.

My guess is that the system will eventually plateau towards mid-decade at around the $11-12 billion mark with a loan/grant mix that in the region of 55:45: that is to say, with about 2x as much loan and 5x as much non-repayable aid as the parents of today’s children had available to them.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Are these numbers indexed? If not, then student support hasn’t really increased.