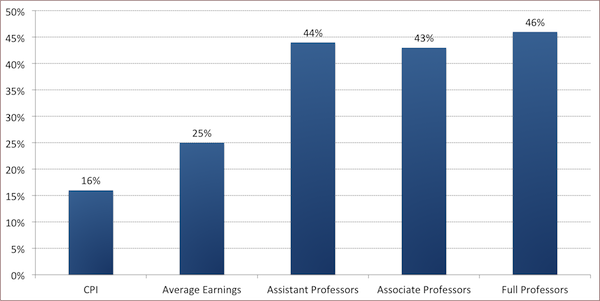

I was browsing through some Statistics Canada data on university salaries the other day, and I rapidly came to the conclusion that there have been few decades in which it was better to be a prof than the last one. As the following table shows, over the years 2001 to 2009 (the years for which I could get good-quality data from Statscan for free – this email’s not paying a paying gig unfortunately), pay for full professors in non-medical disciplines across Canada rose at a rate very close to three times the rate of inflation, and about 85% faster than the average Canadian wage.

Change 2001 to 2009

There was some variation across institutions, of course. Generally speaking, pay increases were slightly higher at large institutions, and were definitely larger the further west one goes. But there was no university where the increase in salary was less than the increase in the national average wage. To put it another way, it’s a perfect Lake Wobegon situation, in that all professors are above-average.

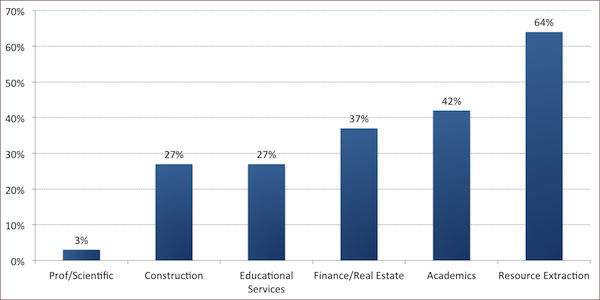

Above-average, but not table-topping. Academics didn’t fare quite as well over the last decade as people from the “forestry, fishing, mining oil and gas category” – miners in particular have made out like bandits since about 2004. But they did fare substantially better than some other employment categories against which they might plausibly be measured: Finance/Real Estate (37%), Educational Services (27%) and especially Professional, Scientific & Technical (3%) (curious what STEM advocates have to say about that last one? Me too).

Increase in Average Nominal Earnings, by Occupation Sector, 2001 to 2009

(If you’re wondering how academics as a whole can be up 42% when every individual rank is up by more than that – it’s a composition issue. Proportionately, there are a lot more junior rank professors than there used to be, and that drags the average down.)

Now the obvious retort here is that by using the lens of a decade, I’m distorting the longer-term picture. To a considerable extent, the rapid rises of last decade were a reaction to the 1990s, when academic salaries rose by slightly less than inflation. That’s somewhat persuasive if you’re comparing academic salaries to inflation – less so to average wages, which also took a beating in the 1990s.

The cause of this? It’s not a drying up of supply – PhDs are being pumped out faster than ever. Nor, as we have seen, is it competition in the private sector – quite the opposite since professional/scientific wages were so weak. In fact, it’s really hard to avoid the conclusion that the cause is simply availability of government funding. The 90s were a decade of restraint and the 00s weren’t – and salaries changed accordingly.

4 Responses

The average wage of the individual professor is on the rises, yes, but it seems that there are also fewer tenure-track positions, as the sessional instructor has become the true workhorse of academia. Could the rise in wages of tenured positions be attributed to not a rise in the availability of government funding, but of equal funds spread over fewer tenured spots, as the underpaid sessional instructors are not noted in these figures?

Hi Bethany. Thanks for reading our stuff.

The short answer to your question is no. In the time period we’re looking at here (2001-2009), faculty numbers in tenured and tenure-track positions went up almost as much as salary: a rise from 28463 to 37266, or 31%. You’ve got new universities opening, or colleges becoming universities, and across Ontario there was a big hiring binge for the double-cohort. Mount St. Vincent, UNB and Moncton are the only institutions that actually reduced faculty head count: in some institutions (e.g. Brock) the increase was as high as 50%.

As somebody who despite having a master’s degree in post-colonial ecofeminism STILL can’t find a job to pay down my 50K in debt, I think it is ridiculous to be casting aspersions on professors inflated wages when the real criminals in this whole thing are patriarchal bankers.

What we need is more money to be put into universities, more funding for students to get degrees. If that means that we end up spitting out a bunch of heavily indebted, over educated moral busybodies with no actual marketable skills, so be it! This is what democracy looks like!