[the_ad id=”12709″]

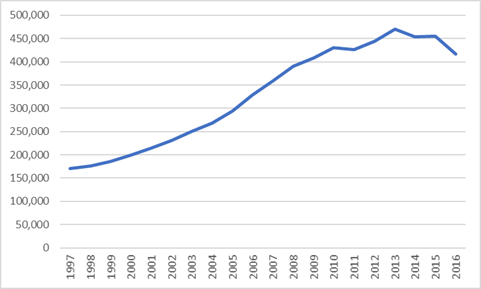

A few years ago, I made the observation that Canada’s big run-up in apprenticeship numbers was highly correlated with the commodity price super-cycle (in particular, the price of oil) and that an era of low energy/commodity prices might lead to a big decrease in demand for apprentices. Time to check on that prediction.

So, first thing to note is that apprentice numbers are down a bit over the last couple of years. Probably not as much as expected if one assumed much of the run-up was primarily driven by oil prices.

Figure 1: Apprenticeship Registrations in Canada, 1997-2016

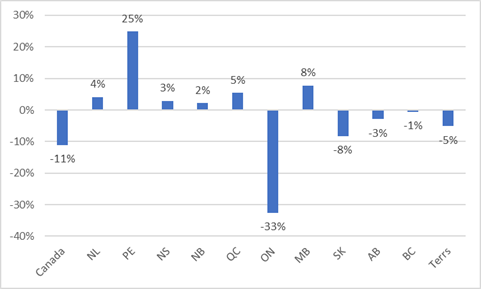

As figure 1 (based on data from Statscan’s Registered Apprenticeship Information System) shows, we hit peak apprenticeships in 2013; since then, overall numbers have dropped by 11%. But, the regional pattern shown in Figure 2 is very odd and suggests something very different from a resource-price driven collapse. Yes, there are small drops in the resource-dependent west and slight increases in the Atlantic (which I suspect is just apprentices formerly working in Alberta and Saskatchewan returning home and re-registering in their province of origin). But the real news is that one province is responsible for over 100% of the drop in apprentice numbers; namely, Ontario.

Figure 2: Change in Apprenticeship Registrations by Province, 2013-2016

Ok, so what is going on in Ontario? Is this like the thing with college enrolments where the province just forgets to report 25,000 students?

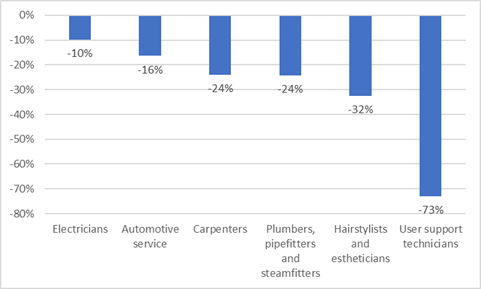

Well, it’s hard to tell from the data. Certainly, there appear to be substantial differences in what has happened to numbers in different trade groups. Figure 3 shows the drop in Ontario’s apprenticeship numbers across the six largest apprenticeship groups in the province (yes, IT support is one of the six biggest apprenticeship groups – which is kind of interesting since it didn’t exist a decade ago).

Figure 3: Change in Apprenticeship Registrations, Major Apprentice Groups, Ontario, 2013-2016

What’s the explanation for all this? There doesn’t seem to have been any economic or policy reason driving these numbers. And let’s assume – perhaps overgenerously – that this is not some kind of statistical glitch (if it is, it’s an odd one – the numbers drop precipitously twice, once in 2014 and 2016 but stayed steady in 2015). The one possibility that really leaves is that Ontario has actually changed the way it counts apprentices.

One of the problems with the way Canadian provinces count apprentices is that it’s really hard to tell when someone stops being an apprentice. “Enrolment” for apprentices doesn’t really mean what it means in other parts of the education system. If an apprentice keeps their job but never finishes their class studies (either because the apprentice has lost interest in gaining certification or because the employer chooses not to release the apprentice for classes for whatever reason), are they still an apprentice? In universities and colleges, we know when someone has dropped out when they stop paying fees, but with no equivalent in apprenticeships, it’s hard to work out when to stop calling someone an apprentice.

This isn’t just a problem in Ontario, of course – it’s a problem right across Canada and everyone in the apprentice system has known this for yonks. But my guess here is that Ontario has just chosen to tighten up its checking and reporting and as a result has seen a fall-off in numbers. If this is what happened, what we’re seeing is an increase in statistical accuracy, not an actual decrease in numbers (it could be both of course, but in the absence of accurate historical statistics, it’s impossible to tell).

That’s just a guess, of course – if anyone from the Ontario apprenticeship world has any further insights, get in touch. Meanwhile, the lessons here are: dig behind the headline statistics and try to understand issues of data quality. Both are crucial to understanding what is really going on in education.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Just a few thoughts-

Unlike nearly all other careers, Apprenticeship relies on an employer to establish and maintain an Apprentice’s status. Apprenticeship training is tied directly to employers’ business environment. In a perfectly functioning system, Apprentices are trained by Journeypersons, who then become Journeypersons themselves. Journeypersons then take a position within their training company’s roster, and the process restarts with a new Apprentice. This model helps employers account for attrition by retirement or employees who leave for other employment opportunities. In a stressed economy or with a relatively young staff group, employees may see benefits to staying in place, and demand for new employees may weaken. Once the employment rosters are filled, it may not make good business sense to bring in more employees if the business climate can’t support more employees. So there can be an “anti-cyclic” pattern related to apprenticeship employment demand. More demand equals more apprentices; four or five years later as the apprentice training finishes, unless the business has grown, there may not be a need to have more apprentices, and the system shuts itself down.

One other phenomenon that could be occurring is the scenario where conscientious employers take on training wholeheartedly. When the apprentice training is complete, there may not be a place for the newly minted Journeyperson aboard the training company’s roster, and they begin the search for work externally. If the economy takes a downturn and larger employers are forced to close down, this can place a large number of well trained people in the job hunting marketplace. When qualified and well-trained Journeypersons are bountiful, the training culture suffers. Training of Apprentices can be affected by the economy, especially when government programs exist to offset unemployment in a region.

The phenomenon the article refers to could easily be explained by the factors mentioned in the article, or by these factors, or a product of each.