Every year around this time, I do a simple piece summarizing all the provincial budgets. I usually wait until all ten are done – so y’all get the full national picture – but unfortunately that’s not possible this year because neither PEI nor Alberta, both of whom quite recently acquired new administrations, are planning on getting budgets out the door before I break for the summer. So, I figured I may as well get the whole thing – or 8 provinces worth – out sooner rather than later. Sorry for the incompleteness, but it’s out of my hands. I’ll try to do an update in the fall after Alberta’s budget passes.

So let’s start, as we usually do, by looking at government transfers to institutions. Same caveats apply as in previous years: what I am doing here is calculating between what was budgeted last year and budgeted this year. This is about changes in government intentions as expressed in budget documents and not government actions in terms of real spending (for instance, the fact that the student assistance program in Ontario overspent its target budget last year by about 25% does not show up at all in these calculations). All figures are adjusted for the consumer price index and expressed in January 2019 terms.

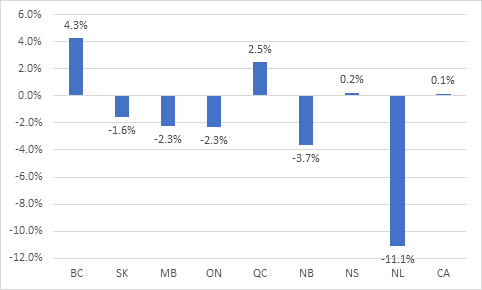

Ready? Here’s the change in government transfers to institutions.

Figure 1: Change in Budgeted Transfers to Institutions, by Province, 2019-20 vs 2018-19

In five of the eight provinces where we have budgets so far this year, institutions have seen a real cut in total transfers. In Manitoba and Ontario, these amount to 2.3% because funding was effectively frozen in nominal terms and 2.3% happens to be the inflation rate. The big cut is in Newfoundland, but this is mostly due to a fall in capital expenditures; operating expenditures were much less affected. On the other side of the coin, the BC increase of 4.3% is not in fact as impressive as it looks as a good chunk of that money gets immediately eaten up by the increase in the Employer Health tax. In terms of sheer dollars, the 2.5% increase in Quebec – an increase of over $150 million after inflation – is the most important and from a national perspective wipes out any losses from Ontario. As a result of all that, what we see is that for the country as a whole, the increase in transfers after inflation is…0.1% (and that will probably turn negative after we get the Alberta budget in the fall).

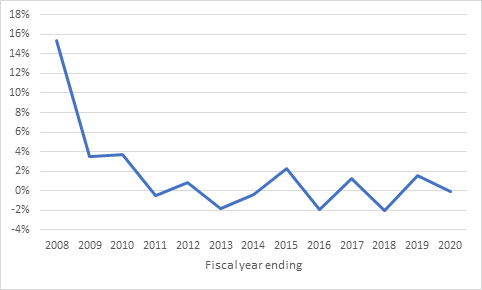

Figure

2 shows the year on changes dating back to the 2007-08 fiscal year (which was

the year the McGuinty government’s increases to budgets in Ontario really

kicked in). From a 15% hike that year, it fell quickly and since 2011 we

have been in a pattern where the annual change bounces between 2% and -2%.

Figure 2: Year-on-year change in Aggregate Provincial Funding, 2007-08 to 2019-20

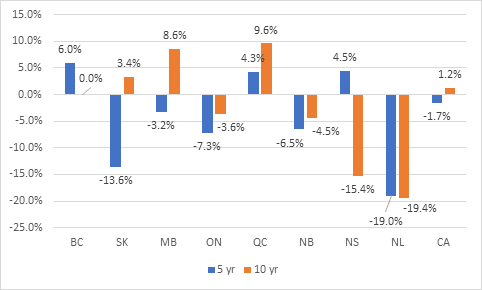

We can also look at the 5 and 10-year picture by province and nationally. It ain’t pretty. Among all provinces, only Quebec can claim that present public expenditures in 2019-20 are higher than they were in both 14-15 and 09-10. And in fact, nationally, we have seen a fall in provincial transfers of 1.7% in real terms.

Figure 3: 5- and 10-year change in Budgeted Transfers to Institutions, by province, to 2019=20

Now, I hate to bring this up yet again but the main thing you should be thinking when looking at these graphs is THREE CHEERS FOR TUITION FEES. If Canadian universities and colleges had had to live exclusively on public money over the last decade, they’d have been screwed. All those years of above inflation raises? The rise in the number of full-time academics? Fuhgeddaboutit. All those higher domestic fees, much higher international fees, and much, much higher international student numbers? That’s what’s keeping the system afloat.

We hit peak public funding about a decade ago. If institutions want more than that, they’re going to need to get it from students or other private sources. If they don’t….well, that’s when the real austerity begins.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Tuition fees might be an ever-more necessary evil, but that shouldn’t tempt us to forget that they remain an evil. Perhaps they’re merely a lesser evil than full reliance on the government of the day.

Speaking of internationalization and the prospect of a shrinking market (June 5th), the marginal financial edge of which many universities are now taking advantage may shrink even if the market holds up. To varying degrees across provinces, domestic student demand for access to higher education has been in a trough. Depending on which projection one relies on, demand will return to pre-trough levels around 2023-2024. When it does, the financial effect of the international market will change. During the trough, the marginal cost of enrolling international students was close to zero; in many colleges and universities they occupied already financed surplus capacity. The marginal financial edge was huge: all revenue and very little, if any, cost. A return to pre-trough levels of domestic demand will soak-up surplus capacity. It is difficult to imagine that any provincial government will tolerate domestic students being “bumped” by international students. In that case, even if the international market holds up, the marginal cost/marginal revenue equation will have changed as accommodating international students will require growth, which in turn will raise marginal costs and shrink the marginal gain as marginal costs approach average costs. It is equally unlikely that provincial governments will fund those costs. This prospect is not so far in the future that colleges and universities that are now counting on international enrolment to balance their budgets should begin now to think strategically about the prospect of places now being filled by international students being filled by domestic students, and the costs of growth needed to maintain current levels of international enrolment. The positive margin might still be there, but it will be smaller.