Back in 2022, just after the last provincial election, I wrote a piece looking forward a few years and predicted that the years 2023-25 were going to be chaos for Ontario postsecondary institutions. And I was right, although I can’t claim to have anticipated any of the specifics. Given that we are now going back into an election, I thought I would try to look into a crystal ball and look at what the province’s postsecondary system will look like financially if our glorious premier is re-elected for another four years.

To do this, of course, requires making a few assumptions, not just about what will happen in the future but, given the inevitable Canadian delays in producing data, what’s been happening in the past two years as well. Hard data on the student numbers which drive aggregate tuition income does not exist beyond 2022 because the provincial government is deliberately suppressing data on this subject. Yes, really. Until last year, Ontario had one of the best records in the country when it came to openness on enrolment stats, usually publishing quite detailed data within six months of end of the calendar year. As of today, it has now been twenty-one months since the last update. By complete coincidence, the data that has not been updated covers the exact period where provincial government was asleep at the wheel in terms of oversight of international student intake. Can’t have that data going out before an election, I guess.

Anyways, that means the following projections require a bit more educated guess work than usual. For transparency, here are my assumptions:

- I have based student number projections for 2023-24 and 2024-25 on data I could find from the Ontario Universities Application Centre (OUAC) and from federal open data on student visas issued up to fall 2024.

- I am assuming that international student enrolment will bottom out in 2025-26 and resume 10% annual growth thereafter, and that domestic enrolment will grow 2% per year, in line with projected increases in the 18-21 population. The assumptions on international students might be too generous, in which case all my projections will be too optimistic. Keep that in mind as you read this.

- I am assuming that the provincial government will not add any new funding to the system beyond what was announced in the run-up to the 2024 budget, but that the extra funding announced as a response to the Blue-Ribbon Panel will be maintained past 2027.

- I am assuming the freeze on tuition will be maintained, but a gentle (but below-inflation) rise in average tuition will continue due to students switching from cheaper humanities courses to more expensive STEM ones.

- I am going to focus on the main sources of institutional operating income, which are tuition fees and provincial operating government. I am excluding from this analysis anything to do with income from federal or private non-student sources.

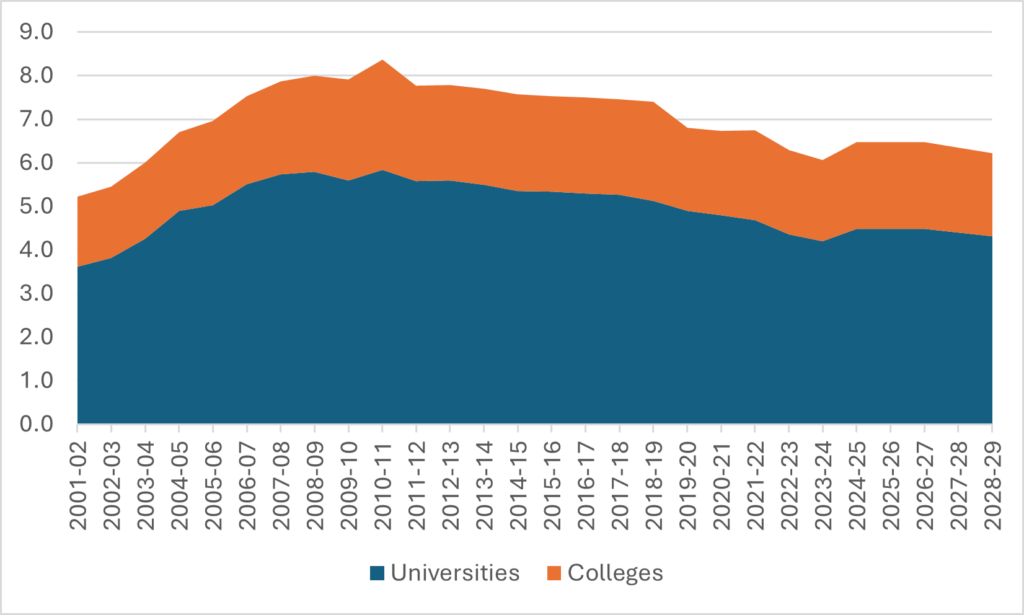

Let’s start with public expenditures on postsecondary education. The problem of falling real public expenditures began well before Ford took power, but this trend has worsened under Ford. Until last year, he consistently allowed inflation to erode funding. The only time he increased institutional funding was in 2024, after the report of the blue-ribbon panel, and even then the three-year package he announced barely allows funding to keep up with inflation. When this new funding evaporates in 2027, the prospects for any new funding are uncertain: I think it is more likely that the government will revert to its previous practice of holding funding constant in nominal dollars but fail to provide any help to offset inflation. Assuming this is true, the path of government funding for Ontario postsecondary institutions will be as shown below in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Ontario Government Transfers to Post-Secondary Education, 2001-02 to 2028-29 (projected) in Billions of $2023

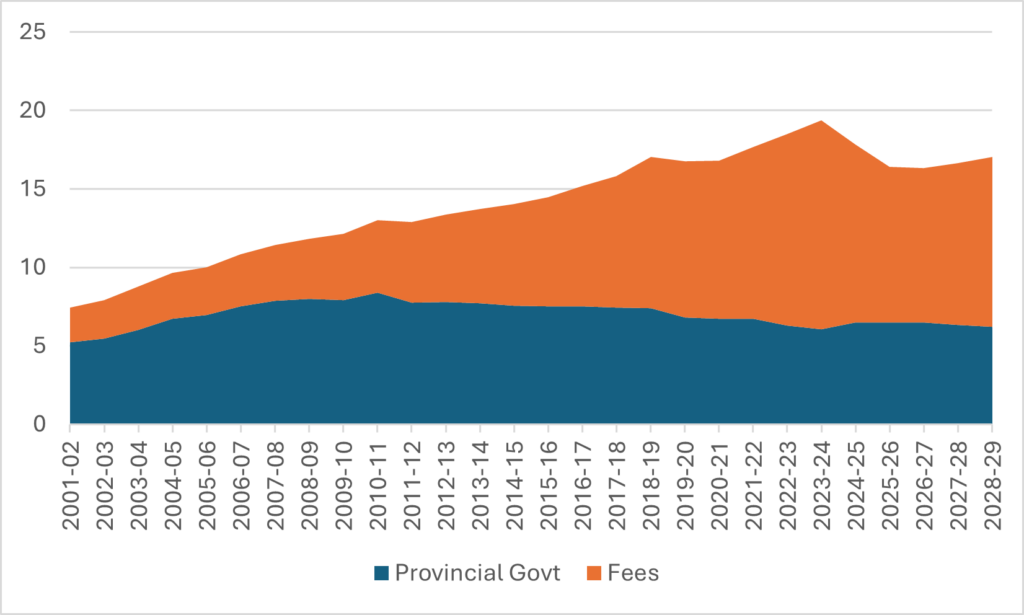

Now of course, public funding only makes up about a third of total funding in Ontario postsecondary education. What happens when you include tuition fees? Well, it looks like the graph below, Figure 2. Again, as you can see, the “take-off” point for the system we have today clearly lies in the McGuinty/ Wynne period, but boy howdy did the Ford team double-down on the model it inherited.

Figure 2: Total Operating Income by Source and Sector, Ontario Public Postsecondary Institutions, 2001-02 to 2028-29 (projected) in Billions of $2023

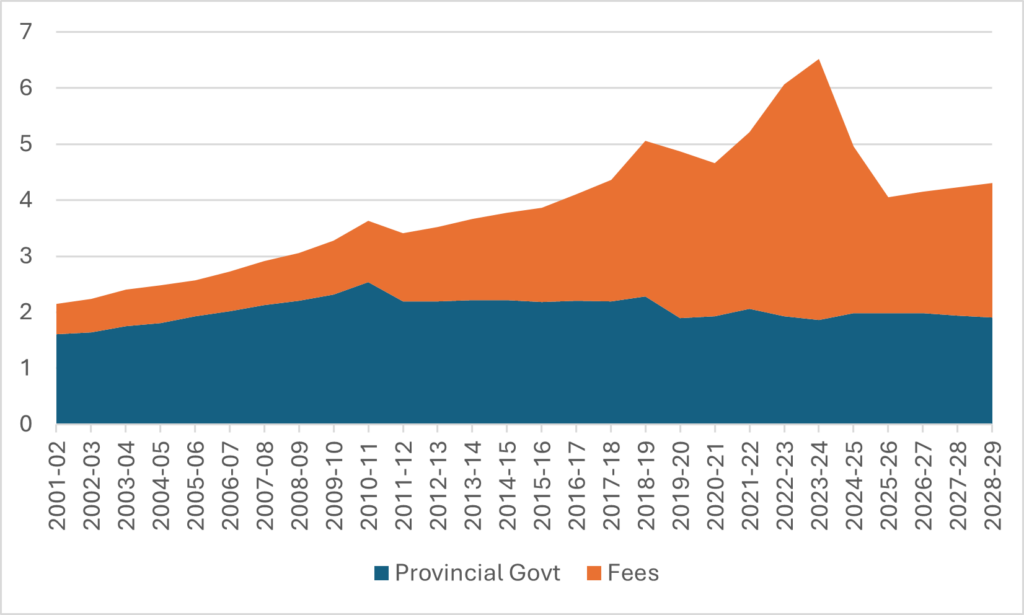

Now, this is one of those cases where it helps to disaggregate what is going on in the system and look separately at what’s going on in the universities and colleges. Let’s start with colleges in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Total Operating Income by Source, Ontario Colleges, 2001-02 to 2028-29 (projected) in Billions of $2023

I’ve been writing about the big fall in college revenues for a few months now, but even I find this graph shocking. Total operating income to the college system is going to crash by about a third between 2023-24 and 2024-25 and then probably will start to recover thereafter. Basically, you should consider the period 2015-2025 as a huge fever dream that is now breaking and sending the system back to exactly where it was a decade ago, minus about 15% of its public funding and a similar drop in the number of students (domestic enrolment really crashed over the past decade).

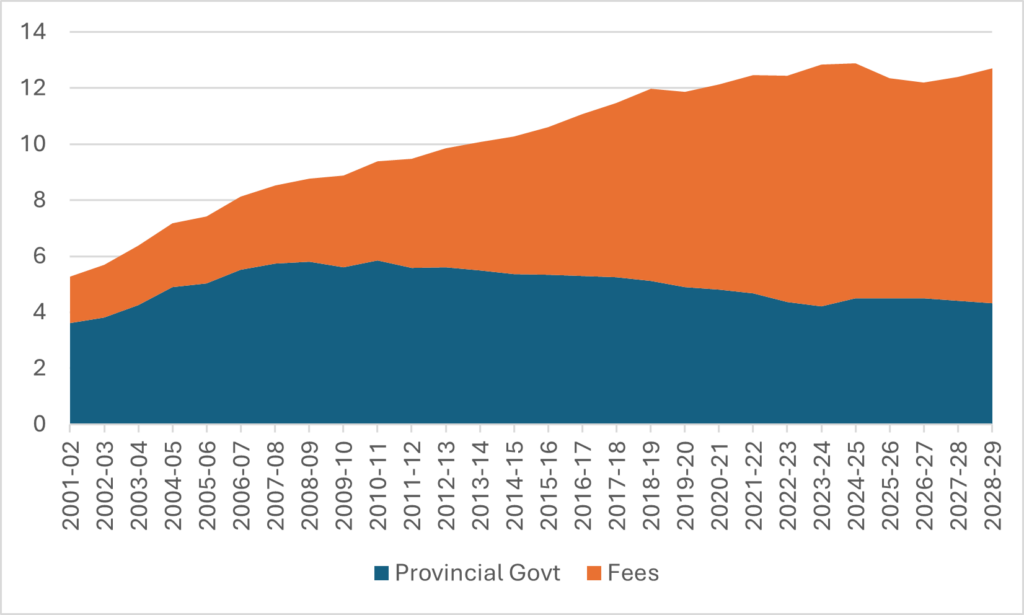

Figure 4 repeats the exercise for universities. This one might seem puzzling for many, because it appears to show very little drop in funding in the 2020s. I mean, yes, there’s a teeny dip in 2024, but absolutely nothing like what we see in the colleges—so why are universities screaming about their untenable financial positions?

Figure 4: Total Operating Income by Source, Ontario Universities, 2001-02 to 2028-29 (projected) in Billions of $2023

Well, the answer is that universities don’t have a revenue challenge so much as a cost challenge. Colleges have an enormous amount of freedom to rearrange or reduce staff. Universities, to put it mildly, do not, partly because of tenure and partly because collective agreements between universities and faculty contain clauses about layoffs and financial exigency which impose very high barriers and costs to any institution that tries to reduce academic headcount. This forces institutions to force as many cuts as possible on non-academic staff and services, but there are limits to how much you can do before students start turning away.

Plus, of course, universities simply got in the habit of getting ever larger. Looke at what happened in the 18 years before the Ford government took power: 17 straight years where the average annual income growth after inflation was 5%. The internal political economy of Ontario universities simply evolved so that growth less than 5% was believed to be “austerity.” Since Ford came to power, annual growth has been effectively zero, even as institutions are dealing with the costs of accommodating the major shift in students from humanities to STEM. The gears inside universities are grinding to a halt and even going in reverse this year and next. And universities are—by design—poorly engineered to deal with a lack of growth.

So, what can be done? Well, in the world we all wished we lived in, this situation would be attracting serious political attention. But it’s not. Ontarians quite like having world-class universities and colleges; they just don’t feel like paying for it. Had the cuts started a few weeks earlier, or had the election been called a few weeks later, the current Program Apocalypse (which seems more than on course to deliver the closure of over 1000 programs across the province) might have become what political animals call “a kitchen-table issue,” that is an issue so important than voters talk about it at the kitchen table. Kids not being able to get into the programs they want to get into because they have been shut due to budget cuts? Yeah, that’s a kitchen table issue. One that might yet have some impact on the election, though probably not a decisive one.

Could institutions do more to make this a kitchen table issue? Yes, they could. At the university level, institutions could be more overt in saying they will no longer be able to support as many spots in expensive, high-demand programs. At the college level, institutions could be more aggressive about closing programs in the skilled trades. So far, they have been very reluctant to do this even though their high cost-per-student should probably lead a lot more of them to be on the chopping block if financial sustainability were a major issue. But institutions are reluctant to do this because it’s hard to play chicken with the government without seeming to play chicken with the general public. And the only way things could get worse for institutions right now is if they lose what’s left of the public sympathy they have. Which is to say: yes, they could be doing more, but it’s easy enough to explain their hesitation in doing so.

Anyways, sorry to readers in the rest of the country for all the Ontario-centricity. If you’d like to know more about how the mess in Ontario—partly due to inept oversight by the Ford team and partly due to an inept response by federal immigration minister Marc Miller—affects the rest of the country (and it does), have a listen to my guest appearance on the Missing Middle podcast last week. Good fun.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post