Tracing Laurentian’s Path Part 2: External Shocks

Broadly speaking, four external shocks contributed to Laurentian’s downfall. First, the Barrie Campus and the costs associated with that experiment; second, the loss of 140 Saudi students in the summer of 2018 following the Canada-Saudi Twitter spat; third, the province’s decision to cut tuition by 10% in early 2019; and fourth, COVID. I’ll add a fifth which was technically not a financial shock but certainly a waste of money. Let’s go through each of these.

The Barrie Campus

Laurentian opened operations in Barrie in 2002 and gradually expanded the number of programs offered there. The government put a moratorium on new programs in 2010, basically as a way of stopping Laurentian from setting up a de facto second campus by stealth. The university did make made a big pitch to create a full stand-alone campus, underlining the point that at the time it was the largest community in Canada which lacked a campus of its own. When the Wynne government turned down Laurentian’s request for financial support for expansion to a full campus in 2015, Laurentian pulled the plug on the campus, which then housed 500-600 students.

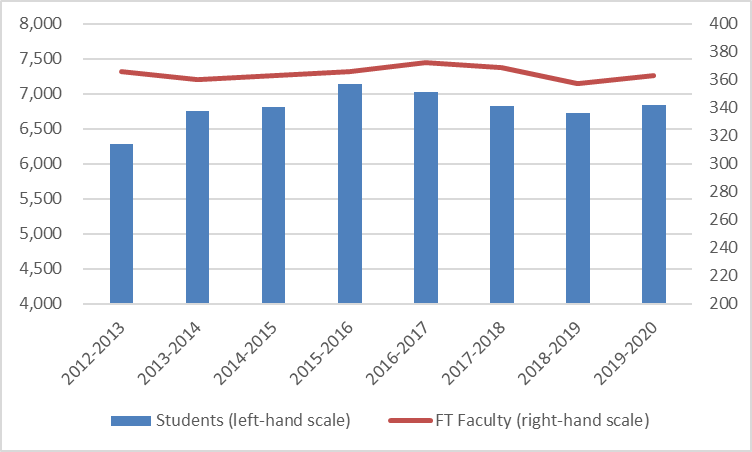

There is no hard data available – publicly at any rate – on how much the Barrie operations cost, or how many people actually worked there, so it’s hard to work out what kind of financial loss this represented. One line of argument is that leaving Barrie cost money because the institution lost students but had to keep the tenured staff it had hired to work there. But with such small numbers, it seems unlikely the campus was working at break-even anyway, so maybe this move saved money. In any case over the long run the ratio between total students and total staff is largely unchanged (see Figure 1 below), so I call this one a wash.

Figure 1: Student Enrolment and FT Faculty, 2012-13 to 2019-20

The Saudi Situation

One of Laurentian’s key weaknesses in the run-up to 2021 was its chronic inability to attract international students. Bluntly, the Ontario system of funding higher education system incentivizes taking international students and Laurentian was an institution that never seemed to get the message.

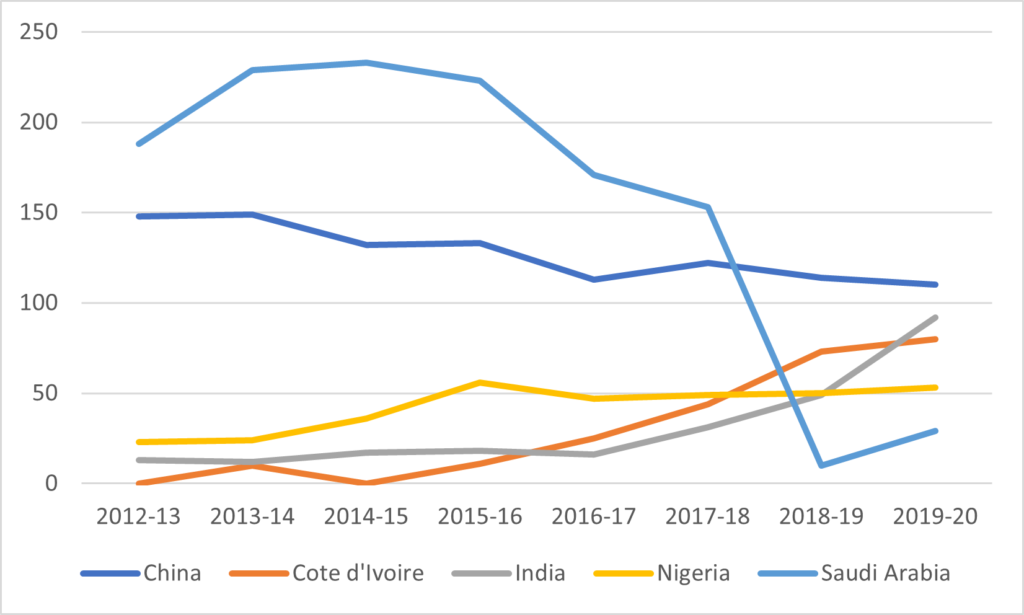

That aside, one of the curious things about Laurentian was that unlike other institutions, it was not over-reliant on China or India. Instead, it was reliant on Saudi Arabia, which was a capricious place on which to depend on international students, as a few Canadian universities could have told you prior to 2018. Back in 2014, when the Saudis began putting controls on the King Abdullah Scholarships, the Saudis essentially blocked their students from attending any Atlantic universities other than Dalhousie. This was a big blow for Cape Breton University in particular, which at the time had something like 40% of its international students coming from the Kingdom (they bounced back by going big on India). Figure 2 shows the effect of the Saudi decision.

Figure 2: Top Five International Source Countries for International Students, Laurentian University, 2012-13 to 2019-20

How big the Saudi effect was depends on your counterfactual. At a minimum, with tuition fees running between $25-$36,000 depending on the program, a loss of 140 students means something like a $4 million one-time-hit for the 2018-19 budget (which, on its own, would have turned that year’s deficit into a balanced budget). Arguably, it had no multi-year effect because total international student numbers rebounded to 2017-18 levels in 2019-20. On the other hand, one could claim that this was a permanent $4 million reduction in income because that extra 130 students who arrived in 2019-20 might have arrived even if the Saudis had stayed (I have my doubts, but it’s possible), in which case the damage is $4M per year, or anything up to $12M across the 18-19, 19-20 and 20-21 fiscals.

The 10% Tuition Reduction

In January 2019, the Ontario government decided to paper over a roughly $1 billion cut in student financial assistance by declaring a 10% reduction in domestic tuition fees for 2019-20, and a two-year freeze thereafter (in theory, this freeze ends in Fall 2022, although I have a feeling that’s unlikely in a pre-election year). As I observed, this measure was always going to hurt institutions with mostly domestic students more than it hurt institutions with a lot of international students. In Laurentian’s case, it was about a $4 million hit from a static baseline (the school took in roughly $55 million/year, of which, very roughly $40 million came from domestic students). In practice, Laurentian only saw a loss of about $2.35 million in tuition revenue in 2019-20, because revenue from international students ticked up a bit (see above) – and of course the university did receive $5.5 million in one-time compensation money from the government’s Northern Tuition Sustainability Fund (a hastily-conceived sop to northern institutions put together once it was pointed out to then-Finance Minister Vic Fedeli that his own hometown university of Nipissing would be among the worst-hit by the tuition policy). Taking all this into consideration, under the reasonable counterfactual where Laurentian increased fees by 3% in both 2019-20 and 2020-21, Laurentian probably did not suffer an income reduction during 2019-20 but faced a $5.4 million loss in 2020-21.

COVID

Laurentian was the first public university in Canada to close its campus in reaction to COVID. On March 11th, 2021, after the first case was noticed on campus (it was related to a mining convention in Ontario, which was one of the country’s earliest major spreader events), the institution decided to move to teaching at a distance.

Almost immediately, the consequences of this decision came into view. According to Laurentian’s 2019-20 financial report, the impact of this decision for March alone was about $5.9 million. Most of this had to do with the collapse in equity values in March 2020, which apparently forced the institution to pay for scholarships out of operating grants instead of the suddenly-depleted endowment funding and the sudden loss of revenue from residents. (The scholarship payment doesn’t make a lot of sense to me because presumably the scholarships had already been awarded prior to COVID hitting, but who knows).

That Fifth Thing

I told you there would be a fifth piece, and it’s this. Remember the $6-million lab the university built for its new VP Research, the one paid for entirely with “internal borrowing” (i.e., in effect by either a line of credit or cannibalizing short-term revenue)? Well, that VP Research, Rui Wang, left suddenly and somewhat mysteriously in order to take what was almost certainly a less important job at York University (deputy provost, Markham Campus, though he has since been promoted to Dean of Science). Since his departure, that lab has essentially been left inactive. $6 million down the drain. I am not sure where, if anywhere, that fault can be laid in this matter, but it is just another among many hits that the institution took in the years leading up to 2020.

Add It All Together

So, here’s the most conservative spin on the math up to March 31st, 2020. Assume the Barrie campus decision was a wash (it probably wasn’t, but we have no data, so let’s put the figure at zero). The 2018-19 year saw the University take a $4 million hit from the loss of Saudi students. The 2019-20 year saw the university take another $5.9 million hit from COVID. And the 2020-21 year was shaping up disastrously: another few million from COVID, and a $5.4 million hit from the domestic tuition cut. Take just those three things, and the 2018-2019 budget would have been balanced, the 2019-20 would have ended in an $3 million surplus, and the 2020-21 budget would probably have been in the black as well. At the end of the 19-20 fiscal, the combined value of the institution’s line of credit, the aggregate net deficit and the “internal borrowing” was about $45 million: without these shocks, they would have been just $35 million: not safe by any means, but heading in the right direction.

In sum: Laurentian was overleveraged and vulnerable in mid-2018. At the same time, it was on a path to de-leveraging. The extent to which Laurentian’s Board and management can be seen as culpable for what happened next really comes down to whether you view the subsequent events as genuinely have coming from “out of the blue.” My view is that i) COVID was a genuine black swan; ii) the timing of the loss of Saudi income was unforeseeable, but it was a volatile enough income source that it should have been hedged against and iii) though tuition cuts were a surprise, the idea that a budget-slashing Ford government would inflict pain on universities and colleges in 2019 absolutely was not: everyone in the sector – and I mean literally everyone – knew that some sort of cut was coming from the moment that government won an election in June 2018. That one just doesn’t wash.

And so, the university began hurtling towards insolvency. More tomorrow.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

What’s the collapse in scholarship equity values in March 2020? Any chance you could give us a short explainer?