Yesterday, I took a quick trip back to the early part of the decade for a reminder of how bad the “skills shortage” debate of 5-6 years ago was. Today, I want to talk a little bit about how we may be heading into something like an actual skills shortage right now, and what the parameters of that shortage look like.

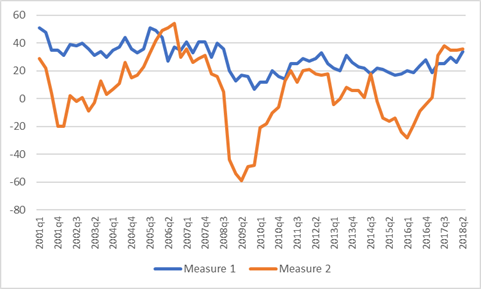

The best place to look for evidence on general skills shortages is the Bank of Canada’s quarterly Business Outlook Survey. This survey asks two questions relevant for identifying skills shortages. The first is: “Does your firm face any shortages of labour that restrict your ability to meet demand?”. The second is: “Compared with 12 months ago, are labour shortages generally more intense, less intense or about the same intensity?” In figure 1 below, I plot positive answers to the first question as “measure 1” of skill shortages, and the net positive answers (that is, positive answers minus negative answers” as “measure 2”. As you can see, both measures are currently sitting in the mid-30s, which has not been the case since the latter half of 2006 when the economy was firing on all cylinders.

Figure 1: Two Measures of Labour Shortages

The Bank of Canada survey does not break down these shortages geographically or by industry or occupation. But Statscan’s quarterly Job Vacancy and Wage Survey – an innovation of the Harper government, and one for which it will never get proper credit – does precisely that. And the picture it shows is…well, not quite what anyone would probably expect.

If one simply looks at the industries with the greatest number of job vacancies, the clear leader is health care and social assistance, followed by retail sales. Utilities (which is a small industry, with only 127,000 workers) has the highest rate of job vacancies at 3.2%, followed by Finance and Insurance at 3%, but their vacancy numbers are dwarfed in numbers by health and retail. If one looks at occupations, however, you get a slightly different story – there it seems clear that the big increases in absolute numbers of job vacancies over the past year are in trades and sales and service, though there is a big proportional increase in finance and natural and applied sciences.

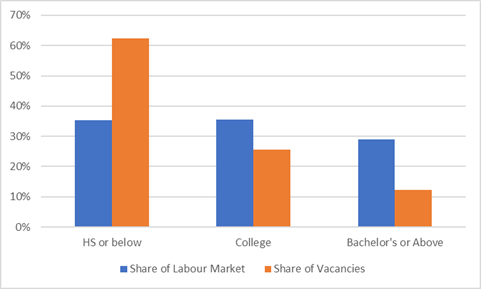

It is also clear from the data that the job vacancies are disproportionately concentrated in jobs with lower levels of education: 61% of vacancies are occurring in jobs with requirements of high school diplomas or lower, even though only 35% of people in the labour market have that level of education. Meanwhile, only 12% of vacancies require a university degree.

Figure 2: Distribution of Labour Market Participants and Job Vacancies, by Highest Level of Education, 2018

Figure 2 shouldn’t be taken as a sign of rampant overeducation–job vacancy numbers are a reflection both of labour market structure and of “churn”, and jobs requiring university education may simply be more stable and turn over less often than jobs requiring low levels of education. But it still suggests that labour markets are somewhat tighter at the bottom end of the educational ladder rather than the top end (which, by the way, makes it an excellent time to raise the minimum wage).

Finally, there is the geographic spread of where the vacancies are. Here, the Job Vacancy and Wage Survey suggests the biggest increases in numbers over the past 12 months have come from Quebec and British Columbia. If you can think of common factors linking those two economies that might lead them to be tighter than the other eight, you’ve got more imagination than I do.

So, broadly, then, what we see is a tightening labour market, but not necessarily a “skills shortage”. To the extent we see higher-level skills in short demand, it is primarily in the health field (as noted yesterday, this is a field with long-term shortages) and secondarily in a few skilled trades areas. The evidence for STEM skills shortages is small to non-existent, which is what one would expect in the face of very large recent increases in enrolment in those fields.

Of course, a lack of data is never going to stop anyone from trying to plead the case of their industry or sector for extra government attention/subsidy. However, thanks to the Job Vacancy and Wage Survey, which was not yet up and running during the last “crisis”, we now have an evidence base for measuring skills shortages than we used to. So, the next round of skills gap talk will be much more rational and enlightened…right?

Tweet this post

Tweet this post