Good morning. Today sees the publication of The State of Post-Secondary Education in Canada, 2018, our first annual review of Canadian post-secondary education institutions, students, faculty, and finances. You can download the whole thing here, you can wait for me to dribble the whole thing out in blog-sized chunks over the next couple of months only with added sarcasm, or both!

But today what I want to underline is what is effectively the lead story from the report, which has to do with the changing nature of funding in Canadian post-secondary education. Specifically, I want to focus on the decline of government funding and the rise of international student tuition as a form of income. For data availability reasons I am going to restrict this discussion to universities, but rest assured what I describe here is happening to colleges as well, albeit on a smaller scale.

Between 2000 and 2009, universities in Canada had it pretty good. We didn’t think so at the time, of course (when oh when do universities ever think they have sufficient funding?) but government grants and student fee income were both increasing at 6% a year after inflation, as was self-generated income until 2007 (stock market losses over the next couple of years put those gains into reverse). There hasn’t been a decade like that for post secondary education since the 1960s.

But after 2009, things changed. In 2009/10, combined government transfers (i.e.. both federal and provincial) to institutions peaked at $19,350 per FTE student. By 2015/16, thanks to a combination of increasing enrolments and a steady erosion of funding, that had declined by 19% to $15,687. Although funding levels recovered somewhat in 2016/17 thanks mostly to that year’s federal infrastructure outlays, there is no doubt that nearly a decade of real funding cuts have left a hole in institutional finances.

[the_ad id=”12811″]

And yet…if funding has been that bad, shouldn’t we have seen the effects by now? Wouldn’t institutions have cut back rather than raise their expenditures by about four percent every year? And the answer, quite simply, is that although government funding has been falling, students have made up the difference, allowing university spending to continue merrily along on the same growth path.

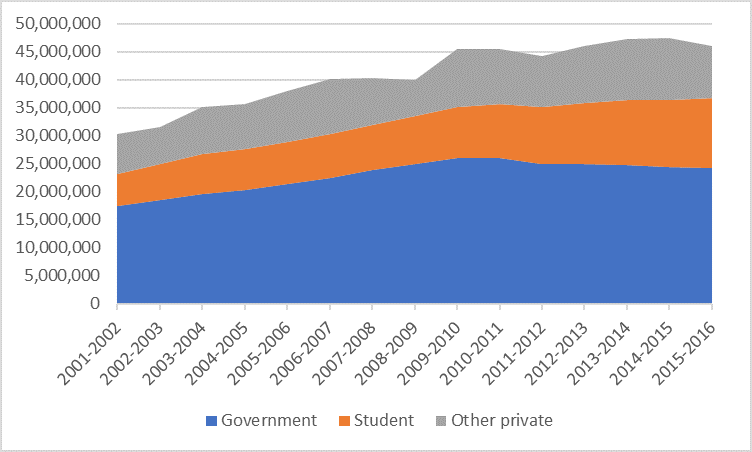

Figure 1: University Income by Source: 1999-2000 to 2016-17, in constant $2016

Now, I know the instant reaction for many on seeing figure 1 will be “those tuition fees, always increasing”. But this isn’t a domestic student tuition issue. Over the past decade, domestic tuition rose an average of 2% per year above inflation, which is exactly the same rate it increased the previous decade. Instead, this is a story of international students, whose numbers almost doubled between 2009-10 and 2016-17, and whose fees rose at 4% every year, to now stand at about $25,000, on average.

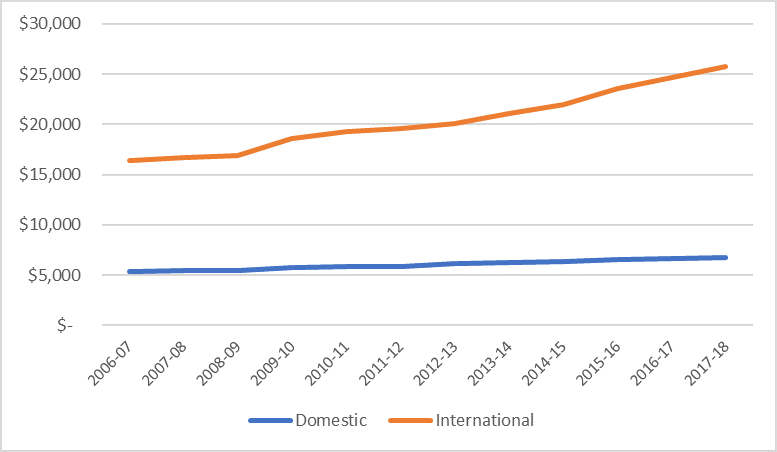

Figure 2: Domestic vs. International Student Tuition, Canadian Universities, 2006-07 to 2017-18, in constant 2018

As figure 2 above shows, over the past decade, international student tuition has grown enormously. The impact of this growth of institutional fee revenues can be seen in figure 3. In 2006, international student fees, then less than $1 billion total, made up 19% of all fees collected at Canadian universities and 4% of total revenues. In 2016-17, this number had risen to $2.75 billion, made up 35% of all fees collected and contributed 9.3% of total revenue. On this current course (and there is no evidence at all that any of these trends are relenting), by 2020 the figures will probably be $4.5 billion, 42% and 12-13% of total revenues. Already some major institutions – including the University of Toronto – are receiving more money from international student tuition fees than they are in operating grants from their provincial governments.

Figure 3: University Tuition Fees by Source in Canada, 2006-07 to 2015-16 in Billions of $2016

The long and short of it is this: between 2009 and 2015, government support to universities fell by roughly $1.6 billion in real terms. In those same years, revenue from international student fees rose by $1.5 billion. Problem solved. Or is it?

There is nothing intrinsically wrong in turning to international students to fill the gap left by flagging government support; certainly, Canada would not be the first country to go down that road. But what we cannot continue to sleepwalk down this road. Making the system more reliant on foreign dollars changes the kind of system we will have. It will be more oriented to the business, engineering and science programs international students want, and less oriented to health, social sciences and the humanities programs that they tend to avoid. It will be more financially volatile and vulnerable to external political shocks, as this summer’s sudden departure of Saudi students from Canadian institutions demonstrates. Given the current demographic trough of young people throughout much of Canada, there is not yet – outside BC anyway – much public concern about international students “taking Canadian students’ places”. But the demographic trough ends soon in most of the country, and domestic student numbers will start to rise again early next decade. What will happen then? How will institutions decide which students to accept? At a system level, it is possible to expand to accommodate everyone, but at prestigious institutions which routinely turn away thousands of domestic students, this could become a hot button issue.

In short, the decline of government funding has been smoothed over by the rise of international students in a manner which to date has been mostly seamless. We should not assume this seamless transition will continue indefinitely. There will be bumps on the road, and the system should prepare for them.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

3 responses to “The State of Canadian Post-Secondary Education, 2018”