Let’s discuss how we talk about cutbacks. And let’s talk about the University of Alberta.

U of A has been rather radically affected by the recent cutbacks imposed by the Alberta government. But here’s the weird thing: apparently it’s not enough to say “we’ve had cuts of 7%”in one year”. Instead, people feel the need to enhance that figure in many ways. It’s not just a 7% cut, they say – “we were told by government to budget based on 2% growth, so it’s actually 9%”. Or, “11% over two years”, etc.

If that’s not enough to invoke sympathy, people turn to statements like: “well we have to absorb a 7% cut, but that’s on top of the 18% we’ve already taken in the last four years.” This, apparently, is a quote from the Dean of Science. I have to hope it’s a misquote, because it’s not even vaguely true.

First, although the government grant fell 7%, that doesn’t mean revenue will fall 7%, because the University can always get new revenue – even with a ridiculous and unconscionable tuition fee freeze – by changing their enrolment mix to favour more expensive programs (professional master’s degree) and students (i.e. foreign ones). In fact, according to a planning document which came out last month, the 2013-14 operating budget for faculties is actually 0.2% higher than it was last year (Science did take a 2% hit, but hey, someone’s got to pay for that 6% bump that Medicine received).

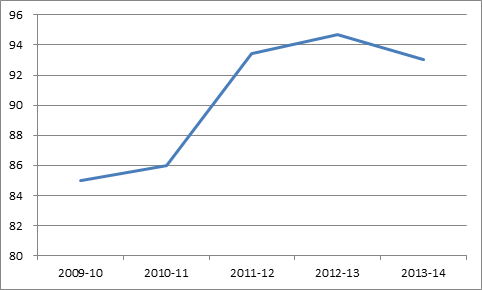

Second, it’s preposterous to say that cuts have been sustained over a four-year period. Here’s the actual budget of the faculty of Science over the past four years:

University of Alberta Science Budget, 2009-10 to 2013-14, in Millions

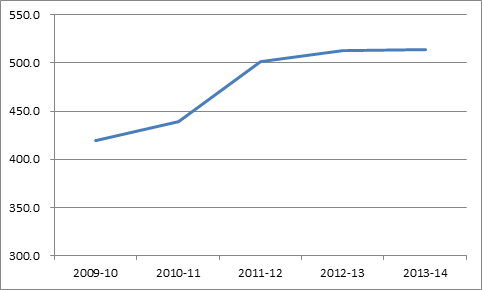

… and for faculty operating budgets in general…

University of Alberta Faculties’ Budget, 2009-10 to 2013-14, in Millions

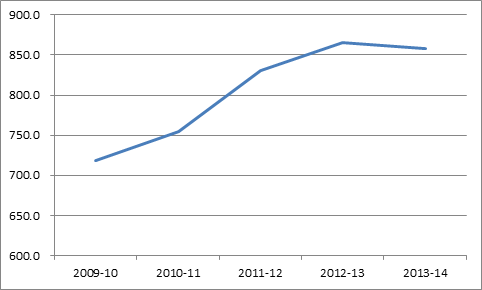

… and total operating budgets…

University of Alberta Operating Budget, 2009-10 to 2013-14, in Millions

The problem, as you can see, isn’t primarily about income. The problem is that when your business is 60% labour costs, and you can’t fire people, and you hardwire-in annual 4% rises in labour costs, there isn’t a lot of flexibility in the system. When revenue growth slows below 4%, cuts – sometimes quite painful ones – do occur… in non-salary areas. Indeed, between 09-10 and 12-13, the Faculty of Science did cut the materials budget by 25%, from 2 million to 1.5 million… but the salary & benefits budget went from 69.2 million to 76 million over that same period. Hmm.

Universities didn’t have to build brittle systems that would shatter if revenue growth fell below 4%. The academic community, through a thousand little decisions, made this bed for itself and now has to lie in it. Yet the dominant narrative is one of universities being passive victims of outsiders’ (i.e. government) actions. A more thoughtful response – one befitting an institution devoted to dispassionate analysis – might be a bit more of an introspective one.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

You had promised earlier that this post would show that the cost of faculty labor was indeed the primary cause of Universities’ difficulties.

I still do not see it. Yes, labor costs account – in all universities – for the whopping % of costs in faculty budgets. Of course!

Faculties are where the core functions of universities are conducted (in my university, they are 90% of faculty budgets). That is where the research and teaching are done. When budgets of faculties are cut, the only thing to cut is indeed labor cost. If their budgets are constant, there still need to be cuts because it is the faculties that bear the brunt of rising labor costs. There you are right.

But faculty budgets are themselves only a part of overall university budgets. The key decisions are made further up, in setting what % goes to faculties (core functions) and what % goes to everything else. Many universities no longer even provide this data to the public (which seems a stunning lack of transparency that I am surprised provincial governments tolerate.)

I am not sure you are wrong, but I – again – fear you jumped to a conclusion too quickly.

I urge you to return to your earlier excellent question: if university incomes are rising faster than the % of total expenditures going to faculty salaries, then where is the money going? If expenditures on faculty are less than one-third of total expenditures, then why is this the only, overwhelming cause of financial difficulties?

A more fine grained study of the evolution of university expenditures is still lacking.

That said, thank you for your work! I only wish for more – (perhaps a bit unreasonably- but these are the questions at the core of a public debate too often driven by facile answers).

Thanks for your comments.

So, what more data could I show you to convince you? If you compare the growth rates in the second and third graphs, you’ll see (well, maybe not “see”, but this is what that data says), that faculties budget increased slightly faster than overall operating budget growth throughout the period (up 22% vs up 19%). So it’s not that funds are being diverted elsewhere (at U of A, at least).

Thanks for the stats, Ryan.

I’m not convinced by the argument that the U of A should address it’s financial shortfall by shifting to expensive programs. Universities have an obligation to students that goes beyond charging the largest amount of dollars in the shortest amount of time. Anyone in biological sciences will tell you that we have a glut of PhDs and postdoctoral fellows facing a very challenging job market. It might help the University to increase the enrolment of foreign students in graduate programs, but it strikes me as unfair to the students. If anything, I think this might be the time to consider a cap on the number of students admitted into graduate programs.

Edan