I’ve been asked a few times for more details on the funding effects of the CAQ’s policies on Quebec Anglo institutions. Unfortunately, it’s a bit difficult to do because neither Bishop’s nor Concordia publish quite enough data to make it possible to do most of the relevant calculations. As a result, what I will be doing today is to flesh out how I see all this playing out for McGill. Some of it will apply at a high level to other anglo institutions, some of it won’t.

(Before I start: I’ll leave an open invitation to anyone at McGill who wants to correct me on my math or assumptions here. I think I’ve got this right at a high level of generality, but I am very aware of the limitations of this analysis. Feel free to correct me and I’ll print the correction in an upcoming blog.)

To begin: most of the talk about the CAQ proposals has focused on tuition fees. And with respect to the claw back on foreign tuition fees, that’s fine, there’s not much to understand beyond the simple claw back. But with respect to the financial effects of disappearing out-of-province students, the tuition fee thing is of almost no consequence at an institutional level. What really matters is how declining out-of-province student numbers affect provincialsubsidies based on enrolment. It’s worth taking a bit of a detour into provincial funding to get a better sense of how changes in domestic enrolment translate into funding.

At a really high level of generality: Quebec spends about 63% of its $4 billion university budget on “weighted enrolments”, another 15% or so on non-weighted enrolments, 10% for “batiments et terrains” (which presumably has some connections with student size), and the other 12% or so on a wide range of targeted initiatives, including subsidies for size/mission/distance from big cities plus targeted dollars for specific programs or initiatives. The weighted FTE calculation – worth $3995 per unit – is designated for “teaching” and each non-weighted student ($2,468 each), is technically for “support for teaching and research”. McGill‘s share of all this for 2023-24 was $451 million. It would be $75 million or so higher, but the government claws back money for various reasons, mainly but not exclusively because of all the tuition it collects from out-of-province students (see my notes on “montants forfaitaires” back here, and for more on the funding formula overall see here).

For additional financial context: If you just look at the operating budget, this amount from the provincial government is augmented by $389 million in tuition (including the montants forfaitaires), plus another $84 million, mainly due to the sale of goods and services. In 2021-22, this all equaled $875 million; this year it’s probably slightly north of $900 million. And this all excludes research income (about $700 million all told, about a third of which is health research performed at the McGill University Health Centre), plus endowment income, donations, special purpose funds, and income from ancillary enterprises, which in 2021-22 comes to about another $300 million. Total budget, roughly $1.8 billion, per the CAUBO/FIUC survey of institutional finances.

So, now, question 1. What are McGill’s gross losses likely to be in 2024-25? This one is relatively simple: the university will lose about $12,000 for every international student it enrolls (that is the increase between the previous montant forfaitaire and the new one; currently the university enrolls around 11,000 international students) and it will lose about $17,000 for every out-of-province domestic student (currently about 7,500 of these) they do not enrol. That is, about $3,000 in tuition and about $13,000 in various forms of enrolment-based funding from government. So total losses will equal

($12,000 * 11,000) + ($16,000 * (7,500 – X))

Where X equals total Canadian enrolment (all ten provinces) in 2024-25.

Now, you can add in whatever numbers you want to make this work, but my guess is that domestic students will tick down by about 8% or so (it would be more, but I suspect that for next year the number of Quebec students will increase to offset the drop in out-of-province numbers). So, run those numbers and what you end up with is:

($12,000 * 11,000) + ($16,000 * (7500-6900)) = $141.6 million

On to question 2. What, if anything, offsets those losses for 2024-25? The obvious offsets come from two sources. The first is an increased number of international students. My guess would be that next year will probably see a net increase of about 500 students; at $27,000 in net income per student (tuition is $44K, the total provincial claw back is $17K), that’s $13.5 million. The second source is from the provincial government itself, which theoretically is going to be re-distributing the income that comes in from the international student claw back. As far as I know, the exact mechanism by which this redistribution will occur is not known. What we do know, though, is that McGill makes up about 20.5% of Quebec’s international students but just 14.3% of total students. If money gets returned to the institution at roughly (14.3/20.5 = 70%) of the level at which it is “taxed”, then the university can probably expect something like $92.5 million in return. Obviously, there is a pretty wide band of uncertainty on that number but put it altogether and that’s about $106 million.

Question 3: So what is the expected hit for 2024-25? If the static hit is $142M but the offsets will be $106 million, then the one-year it will be in the range of $35-6 million, or between 4-5% of operating income, or maybe 2% of total income. Keep in mind there is a big error band here because we simply don’t know how these large montants forfaitaires will be recycled. McGill seems to be expecting a net impact about twice this size: the likeliest reason for the discrepancy is that they have access to more information than I do about how the provincial government will recycle the claw back. But if that’s the case, it’s worth highlighting how much the government can still do to mitigate the impacts of this measure.

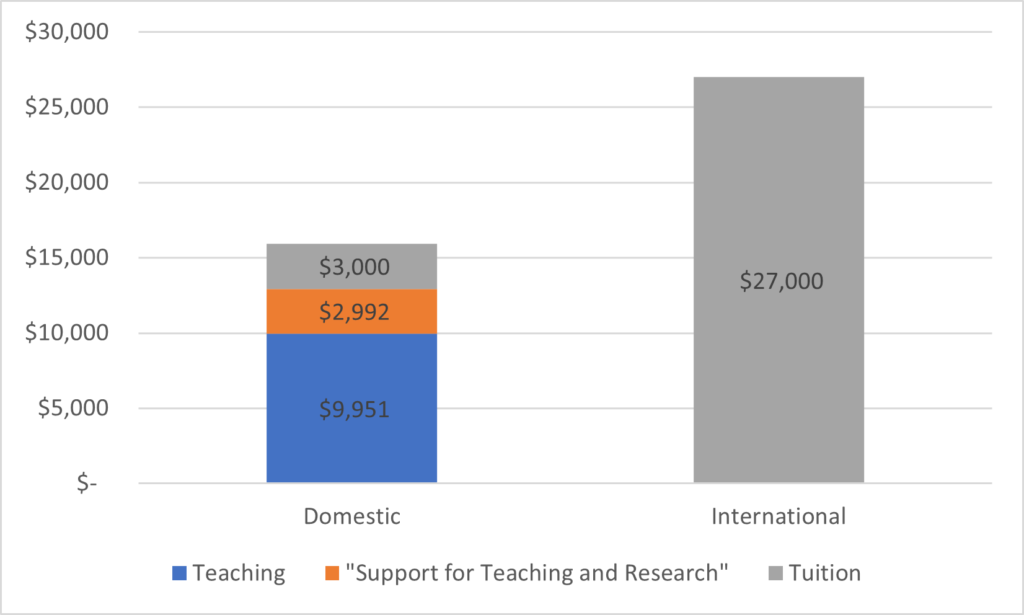

Question 4: What are the expected longer-term financial impacts? The one-year effectsassume very little ability to react to the policy changes. However, over the medium term, McGill will have substantial freedom to alter its student intake in response to its new financial situation and its implicit incentives. For a moment, forget all the stuff about how the government recycles the money for international students and just focus on the actual income per student that McGill will receive, as in figure 1.

Figure 1: McGill’s Net Average Income from Undergraduate and Professional Master’s Students, by Source

Quite simply, even if the Quebec government doesn’t recycle *any* money to McGill for international students, McGill makes about $11,000 in gross revenue every time it switches from a domestic student to an international one. Net revenue? Hard to say. International students cost a bit more to acquire and support, so call it $7,000 per head. But if, over time, McGill loses half its out-of-province student body among undergraduates and professional master’s students (call it 3500 students or so) and replaces each of them with an international student, then McGill actually comes out ahead by about $25 million/year.

And now on to Question 5, the one everyone keeps asking me: couldn’t McGill avoid all this by going private and what would it cost to do so? To which the answer I think is more about politics than economics. I mean, yes, in theory, raise another $450M in revenue per year (what’s another 10K international students, really?) and you could walk away from the provincial operating subsidy. But if McGill remains in Quebec, if the provincial government wants to harm the institution, it’s going to harm the institution. And the CAQ very clearly wants to kneecap McGill. So, while in theory McGill could leave Quebec to become a private institution in another province, it would mean leaving behind much of what makes McGill McGill, not the least of which would be its relationship with the University Hospital Centre, without which its medical program would be pretty much unthinkable.

In short, I am not sure the real story here in the end will be a financial one. It’s easy enough to come up with a scenario where McGill comes out ahead of where it is today, albeit not as far ahead as it would be if the rules had not changed. But for this to happen, it would need to move international enrolments up to about 40% or more of the total, while watching domestic out-of-province enrolments drop substantially. And my bet is that this is a scenario that, given a choice, McGill would forego significant amounts of revenue to avoid. Plus, of course, it does absolutely nothing to reduce the number of English-speaking temporary residents in Quebec. Instead, it just changes where these students come from. Meaning it’s a lose-lose situation: literally no one is getting what they want. It’s an astonishing case of ineptness from the CAQ.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Thanks for your post, it is good to see a look at the numbers in detail. I’m a McGill professor. Although I don’t know details of the funding, I can provide a few more pieces of on-the-ground information for context:

– Behind the scenes, the university is already imposing cuts in anticipation of this policy. My understanding is that all current faculty searches at the university have been paused, i.e. even if the university has approved a faculty hire in particular area, no offers will go out until further notice (I’m sure they will make some exceptions). The James McGill professor and William Dawson scholar programs, which are the research chair programs the university uses to recruit and retain top faculty, have been cancelled this year. This will result in McGill losing faculty, so higher teaching/administrative loads and less time for research for those who remain. This means less research funding coming in, which also hurts McGill’s budget: McGill receives a sizeable chunk of funding in the form of overhead on research grants.

– While the university could always admit more students to make up the budget deficit, there simply isn’t space to do that. McGill already increased student enrolment by 40% over the last 20 years for budgetary reasons (to make up for Quebec’s chronic underfunding of universities). Every classroom is packed full from 8:30am – 5:30pm, there just isn’t space to add more students.

– Students still want to come to McGill, and McGill has lots of room to admit students while still maintaining high standards. But international tuition in many programs is already 60k/year, so I don’t think there is too much room to increase it. So while there is some flexibility I don’t think there is too much.

– My colleagues at francophone universities do not like this policy either, first because they think it will reduce the academic strength of Quebec overall, and second because they view this as part of the governments general reluctance to adequately fund universities. They would much prefer the government to fund francophone universities directly rather than using anglophone universities as a piggy bank. The leadership of most of the francophone universities in Quebec have been in touch with the government protesting this policy. One exception to this is UQAM, probably because they view Concordia as their main competitor.

– Most people believe that long term the government wants the anglophone universities to shrink. And the government has lots of ways, direct and indirect, to accomplish this. You just have to look at the situation at the English CEGEPs over the last few years, where the government has instituted enrolment caps and made it much more difficult for francophones to attend English CEGEPs. Many people look at this and see McGill’s future.

– I agree completely that this is more an issue of politics than of budget numbers. At the end of the day, the government wants to reduce the size of the anglophone community in Quebec. If they really want to do this by shrinking McGill/Concordia, realistically there isn’t much the universities can do to prevent this.

– I think the government views out-of-province students as much more threatening than international students, because international students have to go through the immigration progress if they want to stay, and the Quebec government has complete control over immigration (and has already made it significantly more difficult for international students). Moreover, and this is important: out-of-province students who choose to stay in Montreal have the right to send their children to English school, so are viewed by the government as contributing to the long-term growth of the anglophone community.

Anecdotally, I have several friends who are anglophone Canadians who came to McGill from out-of-province and then decided to settle down in Montreal. They are all bilingual professionals in their 30s and 40s who work either partly or entirely in French, and who chose to send their kids to French schools (at least for primary school). They are all furious about this, because the government is sending a clear message that no matter what they do they will never be considered “French enough” to be welcomed by Quebec, just because they continue to speak English at home.

Thanks again for your writings on this.

Thanks for your post, it is good to see a look at the numbers in detail. I’m a McGill professor. Although I don’t know details of the funding, I can provide a few more pieces of on-the-ground information for context:

– Behind the scenes, the university is already imposing cuts in anticipation of this policy. My understanding is that all current faculty searches at the university have been paused, i.e. even if the university has approved a faculty hire in particular area, no offers will go out until further notice (I’m sure they will make some exceptions). The James McGill professor and William Dawson scholar programs, which are the research chair programs the university uses to recruit and retain top faculty, have been cancelled this year. This will result in McGill losing faculty, so higher teaching/administrative loads and less time for research for those who remain. This means less research funding coming in, which also hurts McGill’s budget: McGill receives a sizeable chunk of funding in the form of overhead on research grants.

– While the university could always admit more students to make up the budget deficit, there simply isn’t space to do that. McGill already increased student enrolment by 40% over the last 20 years for budgetary reasons (to make up for Quebec’s chronic underfunding of universities). Every classroom is packed full from 8:30am – 5:30pm, there just isn’t space to add more students.

– Students still want to come to McGill, and McGill has lots of room to admit students while still maintaining high standards. But international tuition in many programs is already 60k/year, so I don’t think there is too much room to increase it. So while there is some flexibility I don’t think there is too much.

– My colleagues at francophone universities do not like this policy either, first because they think it will reduce the academic strength of Quebec overall, and second because they view this as part of the governments general reluctance to adequately fund universities. They would much prefer the government to fund francophone universities directly rather than using anglophone universities as a piggy bank. The leadership of most of the francophone universities in Quebec have been in touch with the government protesting this policy. One exception to this is UQAM, probably because they view Concordia as their main competitor.

– Most people believe that long term the government wants the anglophone universities to shrink. And the government has lots of ways, direct and indirect, to accomplish this. You just have to look at the situation at the English CEGEPs over the last few years, where the government has instituted enrolment caps and made it much more difficult for francophones to attend English CEGEPs. Many people look at this and see McGill’s future.

– I agree completely that this is more an issue of politics than of budget numbers. At the end of the day, the government wants to reduce the size of the anglophone community in Quebec. If they really want to do this by shrinking McGill/Concordia, realistically there isn’t much the universities can do to prevent this.

– I think the government views out-of-province students as much more threatening than international students, because international students have to go through the immigration progress if they want to stay, and the Quebec government has complete control over immigration (and has already made it significantly more difficult for international students). Moreover, and this is important: out-of-province students who choose to stay in Montreal have the right to send their children to English school, so are viewed by the government as contributing to the long-term growth of the anglophone community.

Anecdotally, I have several friends who are anglophone Canadians who came to McGill from out-of-province and then decided to settle down in Montreal. They are all bilingual professionals in their 30s and 40s who work either partly or entirely in French, and who chose to send their kids to French schools (at least for primary school). They are all furious about this, because the government is sending a clear message that no matter what they do they will never be considered “French enough” to be welcomed by Quebec, just because they continue to speak English at home.

Thanks again for your writings on this.

(The formatting got screwed up the last time I posted this, maybe this is better)