One thing that long marked Canada out as an oddball amongst nations in higher education policy is the reliance of its student aid systems on something called “loan remission”. A series of recent policy moves has nearly eradicated the use of this policy tool.

Loan remission is pretty simple. Students take out a loan at the start of a year of studies and then before repayment begins some of it gets written off. Sometimes it’s done annually, sometimes it’s done on a per-degree basis – the main thing is that what ends up getting paid back is less than what is loaned. There are a few variations on this theme, mainly based on what the conditions for remission are. A lot of US states use some kind of “workforce-based loan remission” where the loan forgiveness doesn’t kick in for several years and is dependent on someone working in a certain field for a certain period of time. Another variation involves working in a particular place for a particular time – usually doctors and nurses in rural areas, a policy that has been embedded in the Canada Student Financial Assistance Program (CSFAP) since the Harper years. In Germany, anyone who graduates in the top third of their class gets some of their BAFöG loan remitted. But most often, in Canada (and also the Netherlands), it is simply: did you finish your year/degree? Yes? OK, we’ll write-off some of your loans.

The way it tended to work in Canada was simple. You applied to your province for a loan, and between the provinces and the CSFAP (then called the Canada Student Loans Program or CSLP), they would come up with a loan package for you. Maybe they would give you something like $9,000 for the year. If you finished, it would get bought down to a threshold. In Ontario, for many years, that threshold was $7,000 (different provinces had different thresholds, but the idea was the same), so in that case they would write off $2,000. Provided you finished your year of school, there was functionally no difference between getting a $7000 loan and a $2000 grant and getting a $9,000 loan of which $2,000 was forgiven by the provincial government.

Now, this arrangement may sound a bit strange: why deliberately delay the payment of a grant when basically all the literature about grants suggests they really change behaviour if they are delivered at or before the point when students enrol. Why deliberately use money in the least effective possible way?

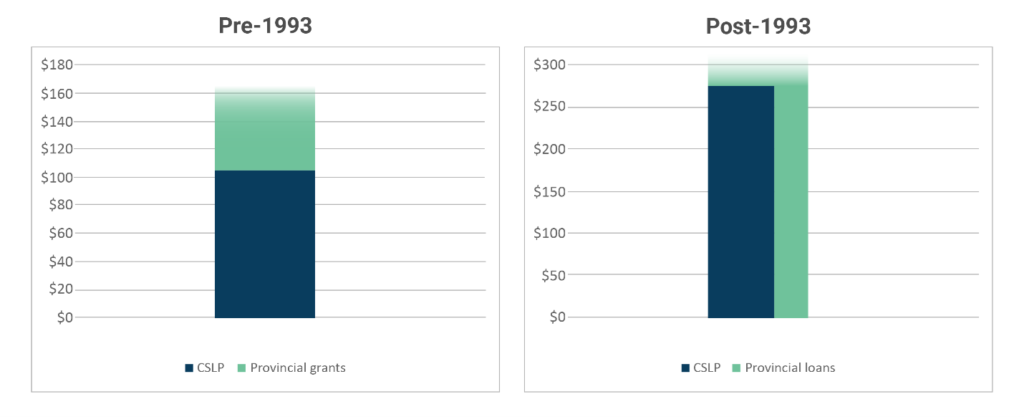

Well, the basic reason is that apart from Alberta, which introduced the first remission program in the 1970s, most provinces introduced loan programs in the 1990s, when the country was falling apart and at least one province was flirting with bankruptcy. But it was also the time when the federal government raised the weekly maximum loan aid to $165, but at the same time decided to meet only 60% of assessed need (see figure 1 below). The implication was that provinces would meet the other 40% (ie $110/week for a total of $275 in aid per week). At the time most provinces were only providing $50 a week, but in grants, and only to a limited number of students, so this federal move put big financial pressure on provinces at a time when they were already very stretched.

Figure 1: Student aid configurations in CSLP-zone pre-and-post 1993 Student Aid Changes, in current $/week

What provinces did, by and large, was to come up with a compromise solution: they would expand their systems to match the new federal program, but a) they would do so with loans instead of grants and b) knowing that this would make student debt shoot up, they introduced remission schemes that would limit debt. But, these schemes usually came with caveats. For instance, in the early years, provinces often made students apply for remission, and made it conditional on finishing a year, both measures which reduced take-up and costs. And, crucially, they would hold off on paying the remission until graduation, a measure which gave them a critical two-or-three year lag between incurring an obligation and paying it. In the depths of the early 90s recession, this lag mattered a lot. Later, various provincial auditors general would tell the student aid agencies to knock it off, make remission automatic and book costs in the year they were incurred, all of which diminished the appeal of remission as a policy instrument. But inertia kicked in and these programs were kept on the books for another couple of decades.

(The attentive among you will have noticed that I keep talking about provincial student aid programs. What about the feds, you ask? Well, with the exception of the aforementioned program for doctors and nurses and a specialized loan remission program for students with severe and permanent disabilities which it had to set up after losing a lawsuit, CSLP/CSFAP never really got into loan remission the way the provinces did. The Millennium Scholarship Foundation – a vector for federal money that existed from 2000 to 2009 – did do so, a bit, but in most years this source never accounted for more than 20% of the national total.)

Figure 2 lets you see how this all played out. At the start of the 1990s, loan remission was non-existent. Later in the 1990s it came to encompass more than half of all non-repayable aid distributed by provinces (though this was in part because Ontario had to pay out several years of remission in a single fiscal year to fall in line with its auditor general’s rules on accrual accounting). At the time, every single province had some kind of loan remission program. Annual disbursements shrunk in the late 1990s but then bounced back mainly because Ontario was so reliant on this as a means of delivering aid. By 2013-14 over $681 million per year (in $2020), or 38% of all non-repayable aid, was being disbursed through remissions.

Figure 2: Non-Repayable Student Aid from Provincial Sources, by type, in millions of $2020

But then, suddenly, everyone kind of fell out of love with the idea. Saskatchewan got rid of its student bursary system, which was a kind of back-end loan write-off. BC shifted its system to a front-end program in 2020-21. And Ontario got rid of remission entirely and shifted to a system of upfront grants when the Wynne government introduced its system of targeted free-tuition in 2016. As a result, in 2020-21, provincial student aid programs only spent $38 million on remission equivalent to only about 2.5% of total non-repayable aid, with nearly half of that coming from just one province, Alberta.

So, its sort of full-circle for remission – from a small, mostly Alberta thing to a small, mostly Alberta thing in about 30 years. But in the interim, for reasons which mostly had to do with i) policy-making in a fiscal emergency and ii) good old fashioned policy inertia, Canadian provinces were surprisingly reliant on a deeply sub-optimal policy instrument. And we should try to remember sub-optimal policies, the better to avoid them in the future.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Hello! I was hoping you could help clarify the following sentence:

“As a result, in 2020-21, provincial student aid programs only spent $38 million on remission equivalent to only about 2.5% of total non-repayable aid, with nearly half of that coming from just one province, Alberta.”

As far as I am aware, Alberta does not have a loan remission program and has relatively (at least I had assumed) few non-repayable grants. The Alberta equivalent to loan remittance I would think would be the Loan Relief Completion Program (LRCP), which was done away with in like 2011-ish (maybe 2012?) in place of a $2000 completion grant, which was also scrapped a few years later.

Maybe I am reading this sentence wrong, but would love to hear more about it. Thanks so much!