No matter where I go, people ask me “what alternative financial models are there which don’t require us to go all-in on international students?” Not because they have anything against international students, of course: rather, they just find the increasing reliance on this source of fee income as inherently more dangerous/volatile than other sources of income (though I’m not 100% sure that’s actually true).

There are two alternatives, which can be combined in various ways. One I have discussed at length on this blog: the prospect of higher funding from government-controlled sources which is to say, government transfers and domestic tuition fees. I suspect there will be some of that in western Canada in the next decade as population pressures continue rising buton the whole my guess is that post-secondary is not getting any increases in per-student funding any time soon. Health care, child care, and half a dozen other things are all simply further up the funding priority list and in any event politicians seem no longer to believe in economic growth, let alone that universities and colleges are assets to be used in striving for it. And as for tuition increases: in an era where “cost of living”, framed as a consumer issue rather than a labour issue, is the #1 voter concern, you can forget major increases.

The second alternative is simply to spend less.

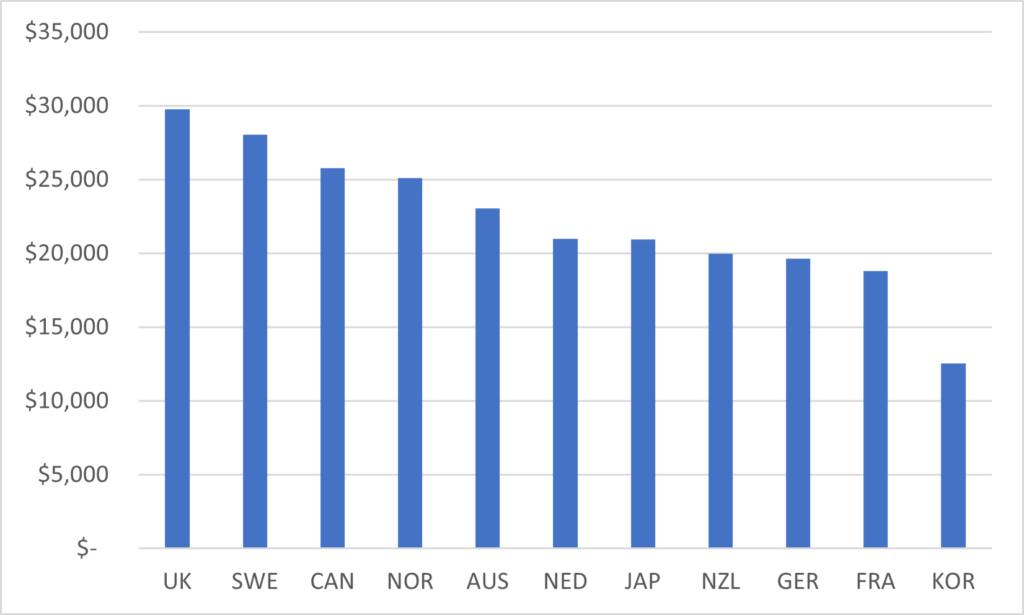

Figure 1 uses OECD data from 2019 to compare per-student total university expenditures by country. On the whole, Canada looks pretty good against most countries against whom we normally compare ourselves (I have left US data out because it’s impenetrable, but my guess would be that we’re close to even with them if we look just at public universities, and way behind them if we include their privates). We can’t really claim that our institutions are especially lean or hard done-by in international terms: clearly, there are ways to deliver degree-level education for less than we currently do.

Figure 1: Total University Expenditures Per-Student, in 2019 USD at PPP, Selected OECD Countries

(My apologies to all folks in the colleges, I’m not going to graph the OECD data for your sector because it’s not really apples-to-apples – mainly for reasons I outlined back here – but if anything Canada looks better against this group of comparators).

If you want an example of what is possible in terms of reducing costs, look at the University of Alberta, which bore a disproportionate burden of the recent cuts to funding in the rest of the Alberta. In total $171 million was shaved off the main provincial grant between 2019 and 2022, a cut of about 25%. Part of U of A’s response has been to seek new revenue sources, including international students, but it also managed to cut expenditures by $120 million last year, mainly by reducing services previously provided at the faculty level and replacing them with services which are grouped in three “colleges” that are sort of super-faculties organized to mirror the tri-councils. Those cuts were painful – several hundred positions were eliminated though there were no layoffs for academics – but the university did manage to reduce its salary expenditures by about $70 million over two years.

Now, one might contend that this is easy enough for Alberta to do, since they started out a standard deviation or more above the national average for funding and all this does is bring them to where everyone else already was, and there would be some truth to that. Making cuts of similar magnitude in Ontario would probably be an order of difficulty higher. It would almost certainly require undoing some significant trends in student affairs, reducing faculty-level provision and the more expensive bits of mental health provision. It would mean more outsourcing of services, particularly IT, and a reduction of staff in administration. It would mean reducing services at the departmental level which may in turn lead to mergers (especially in humanities, which tends to give departmental status to some niche specialties rather than folding them into larger disciplinary units). And above all it would mean being a lot more ruthless about enforcing minimum class sizes at the undergraduate level (small classes being the true black holes in university budgets). That might, eventually, lead to program closures where it becomes clear that too many classes in a program can’t be held due to minimum class-size rules.

(Some of the work of reducing real costs is already being done by allowing inflation to eat away at wages. That’s not good for employees, but it does make institutions a bit more viable).

I think at large institutions – universities anyway (I believe the large Ontario colleges are all pretty good about the minimum class-size rule) – this approach could work. But it will be very hard to make work at smaller institutions, which simply don’t have as much duplication to eliminate to begin with. In those institutions, I think it’s more likely that making ends meet without international students means wholesale faculty closures and/or real wage declines (which will make recruitment that much more difficult). And as for institutions in the North, where per-student costs are 3x or 4x the national average precisely because it’s impossible to put together revenue-generating class sizes, attempting this kind of thing will only produce carnage.

To be clear, this path isn’t one I advocate. But absent a major change in government funding, this path is the only one available if one rules out more international student income. To repeat something I said back in August, all the net increase in Canadian PSE institutions’ real income for the last decade has come from international students. Tout. 100%. The whole she-bang. If new domestic sources of income are forbidden to institutions, they can ride the international student money tiger, or they can restructure to reduce costs. There is no third way.

Personally, I think institutions would be wise to follow recruit students and cut costs simultaneously rather than betting the farm on one or the other. But I also think it’s easy to see why so many take the path of least resistance and just go the international student route.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Dear Alex,

Great piece and I’m in agreement with MOST of what you’ve outlined. One of the things I’m going to disagree with you on however is the last point about alternatives. There IS in fact another way which combines some of the efforts you’ve detailed. For a start, student retention efforts haven’t been as fully deployed – or embraced – as they could/should be at most postsecondary institutions. Another area of alternative revenue is continuing education and lifelong learning. TMU’s Chang school is probably the best example of this in practice but almost every continuing education / professional learning operation in Canada generates net revenue.

Several externals like Google, Juno College, Lighthouse Labs, are continuing to aggressively push into the adult learning market which, post pandemic, has seen its largest participation jumps in decades.

All to say, there is a ‘3rd’ way which can/does provide a solid source of alternative revenue to its institutions.

All the best,

Frank

Thanx for this.

I understand that politically fee increases = cost of living increases, but with well designed student loans fee increases = cost of living increases only for those with reasonable incomes and so should not be a big policy concern. But I also understand that politically cost of living increases is a problem even for those with reasonable incomes.

Additional cost cutting measures adopted by the harder pressed Australian universities are increasing the number of teaching-intensive academics with Australia’s weak form of tenure, increasing the number of teaching-intensive academics on renewable fixed term contracts, and increasing contingent academics.

Good piece Alex,

the second alternative only gets more daunting if we start breaking down, say for example, faculty costs.

When mandatory retirement was abolished in 2000s, Canadian post secondary faculty over the age of 65, jumped to about 11% of total faculty, from a rate near 1%. (about 70% of those are male).

This more senior cohort has more seniority and more time in the business. Meaning they are paid much more than the more jr. Associate or Assistant professors.

This cohort will most likely only continue to grow in university professor totals. Meaning more money to less total professors. As well as potential for losing more Associate and Assistant profs because they grow tired of waiting in the wings.

Pointing back to Alternative 1. An endless market of literally billions – India and China alone, then add in rest of Southern Asian countries. Smaller post-sec will most likely never wean themselves off tuitions that are 3-5x domestic. That is, until geopolitical factors force them to. (e.g. Saudi Arabia in 2018).

I’ll agree with Frank here, there could be ways of increasing revenue without necessarily increasing cost, this requires a good understanding of the underlying costs of teaching on a subject-by-subject basis as well as when, where and how it’s taught. We did some analysis with the University of Melbourne Center for the Study of Higher Education on what are some of the key drivers of teaching costs https://melbourne-cshe.unimelb.edu.au/research/research-projects/policy-and-management-in-higher-education/cost-of-delivery-of-teaching – no surprise class size is a major factor, the trick here is knowing what is the “right” size when it comes to break-even as well as quality of teaching/learning. Having visibility into the details of individual subjects can also highlight subjects that may be delivered at multiple different locations over multiple different times that may be able to be consolidated.

The other major factor with respect to university cost is the large cost of research. Research is greatly subsidized by teaching, and research is something that is very important and for the greater good, so should be a high priority for Governments, but I won’t hold my breath waiting for increased research funding. If Governments would fully fund research, then this could allow institutions to reduce tuition and still generate good surpluses for universities! I would think it would be a win-win-win – students, institution and society!