A few months ago I wrote a piece on inter-provincial mobility in Canada in which I a) noted that in absolute terms, Alberta was the country’s largest net-exporter of students and b) this was a big change from 15 years ago when it was one of the larger net-importers. When I pointed this out, I had a number of people on Twitter make assumptions about the deterioration of prospects for young Albertans, particularly after the collapse of the oil industry/arrival of the UCP. Basically, no matter one’s political POV, Alberta’s net-exporter status could be used to tell a politically advantageous story.

The problem is, if you look at the data year-by-year, none of these stories really make much sense.

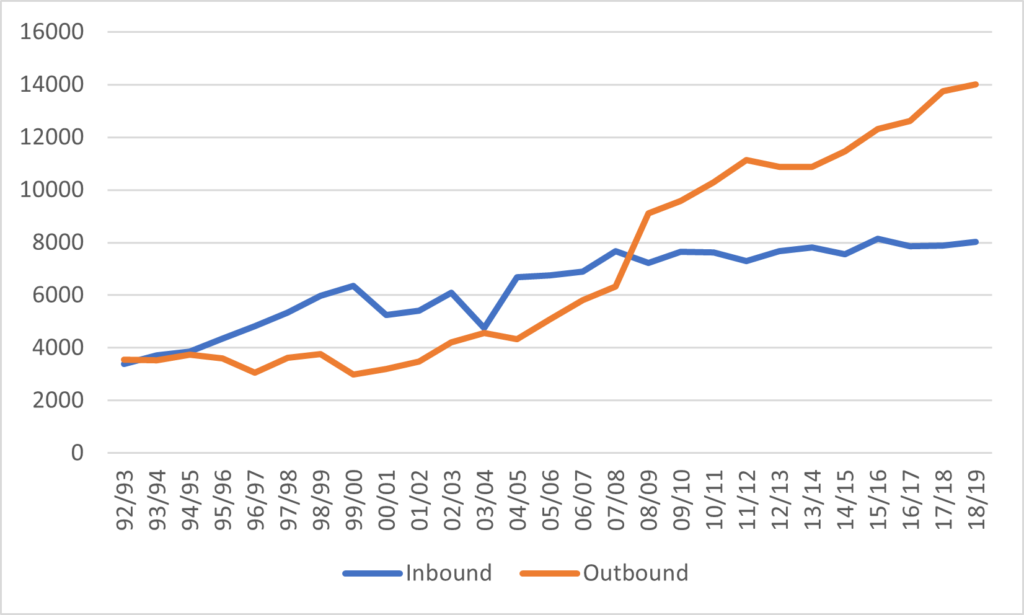

Figure 1 shows the total number of inbound and outbound students to Alberta for every year from 1992-93 to 2019-20. What it shows is the following: in- and outbound students were in rough equilibrium in the early 1990s. Then, during the 1990s, the number of inbound students rose significantly while the outbound numbers remained low. There was then a period from about 2001-02 to 2007-08 when both in and out-bound numbers increased; but after that, inbound numbers stayed constant while out-bound numbers rose by 133%.

Figure 1: Inbound and Outbound students, Alberta, 1992-93 to 2018-19

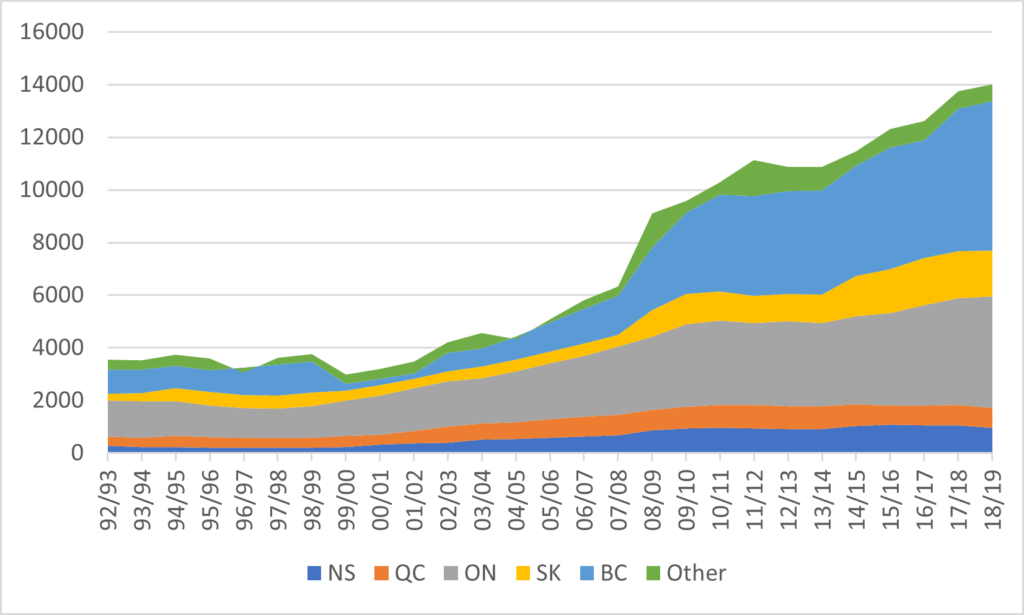

Where did all these students leaving Alberta go? The answer is “pretty much everywhere”, but the largest destinations were Ontario (now taking about 4000 students per year) and British Columbia (over 5000 students per year), but growth in outflows to Quebec and Nova Scotia have increased fourfold and sixfold, albeit from small initial base numbers.

Figure 2: Outbound Alberta Students by Destination Province, 1992-93 to 2018-19

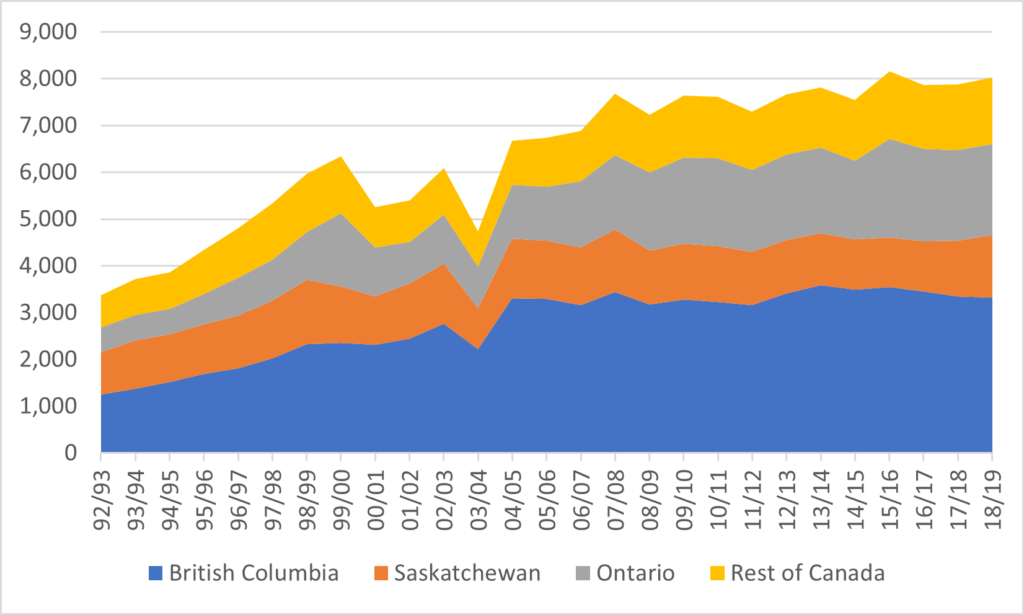

Figure 3 shows inbound students’ province of origin. This has changed very little over time, with British Columbia always being the #1 sending province. Ontario overtook Saskatchewan as the #2 province in the mid-00s, and ever since, Ontario and BC together have accounted for something like 60-65% of all inbound students.

Figure 3: Inbound Alberta Students by Province of Origin

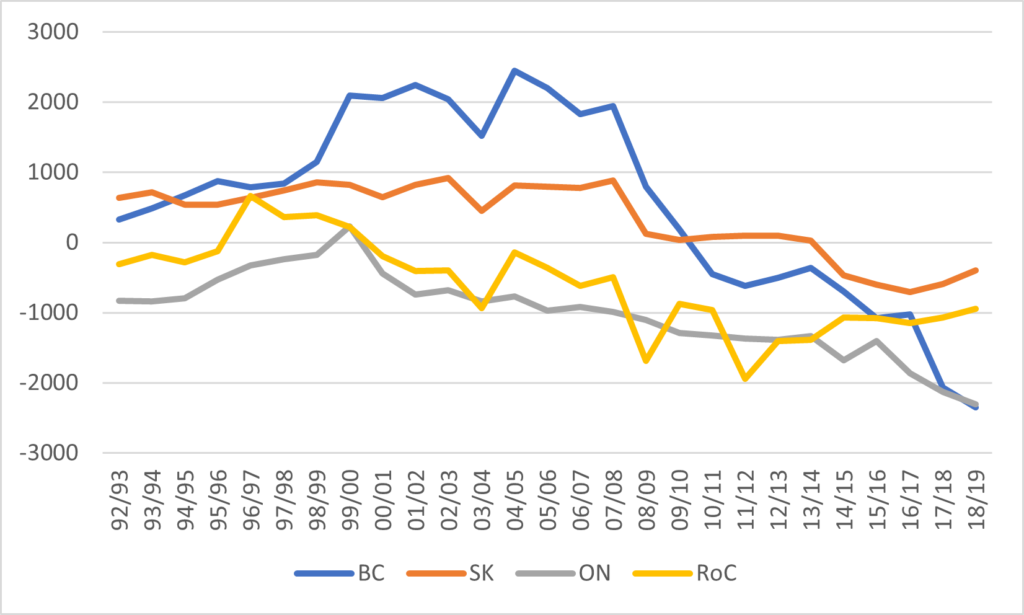

What’s astonishing about some of these numbers is how the bilateral exchanges have changed over time. Alberta has nearly always run a deficit with Ontario, but it used to run very large surpluses with both British Columbia and Saskatchewan. In both cases, these deficits started to fade very quickly after about 2007-08. In British Columbia went from sending 2000+ students (net) to Alberta, to receiving that many. And as for Saskatchewan? Well, for decades it was seen as simply normal that Alberta universities – specifically U of A – would poach the provinces’ best students. But since 2014-15 the flow of students has in fact been moving in the other direction.

Figure 4: Net Balance of Student Flows Between Alberta and Selected Provinces, 1992-93 to 2018-19

Ok, so now how should we interpret all this data?

First: quite obviously, this isn’t a UCP-related phenomenon. I mean, the data doesn’t even get to the point where the UCP took power. It’s possible things have got worse since then – I have no knowledge of this either way.

Second: it isn’t an NDP-related phenomenon, either. Yes, the student deficit increased under the Notley government, but the numbers were rising well before the NDP took power in 2015.

Third: it isn’t related to the drop in oil and gas prices. See above.

Fourth: it isn’t related to any decrease in funding. In fact, weirdly, the big run-up in outbound student coincides almost perfectly with the (Conservative) Stelmach government starting to pour bazillions of dollars into the sector in the mid-2000s, making it – for about a decade anyway – by far the best-funded PSE system (on a per-student basis) in North America.

Fifth: it doesn’t obviously seem to be related to a shortage in the total number of university spaces, either. Alberta’s transition from importer to exporter coincides almost exactly with Mount Royal and MacEwan switching status from college to university.

So, what, then? Well, I don’t have a definitive answer but here’s my guess. Between about 2000 and 2015, the province’s two major universities, Alberta and Calgary, chose to grow their enrolment at rates similar to those seen at similar universities in Ontario and British Columbia. This was very helpful in terms of turning both those institutions into research powerhouses – more $ per student! – but made it difficult for a growing Alberta population to get into the most competitive programs. Given that Alberta was Confederation’s most affluent province for most of this period, a fair number of these students were able to afford the option of eschewing other local institutions and instead headed for UBC or equivalently prestigious universities further east. Meanwhile, though these institutions allowed more non-Albertans through their doors, by and large they chose to prioritize high-paying international students over Canadians from other provinces.

I can’t quite prove that this is what happened – it’s just a story that happens to fit the facts. But I’d be surprised if the real answer is much different than this. Long story short, it’s probably more a story about institutional decision-making than it is about broader provincial politics or economics. And it has nothing, and I mean nothing, to do with the present government.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

I think that your explanation makes a lot of sense from 07/08 to 12/13. Though it needs to be combined with the fact that fairly or not, Ontario and BC universities seem to have a cachet in Alberta that Alberta universities do not have.

The second rise from 13/14 goes along with the drop in oil prices and the damage to the provincial economy. So some of that rise may parallel economic blues and the sense that it might make more sense to study somewhere else where there might be more jobs.

I noticed this trend when I moved to Alberta in 2015. What I figured out is that Alberta, being a net importer of professionals had a different understanding of the purpose of provincial institutions. In BC governments felt that students who studied in BC would stay in BC, and that was a good thing. But Alberta had had decades of well educated people moving there from other places (it was a running joke that no one is actually from Calgary, they just moved there for work), so governments didn’t need a way to retain people through education. It wasn’t even a consideration.

I still think it’s a strange way to see it, but they expect that the students who leave the province for education will come back for work. Since that was true for so long I’m not sure that I can blame them.

The greatest change displayed in Figure 2 is the increase in Albertans going to BC after 2003 and especially after 2008. While factors within Alberta probably contributed, this might also reflect changes within the BC university system.

This would coincide with the transition from Okanagan University College to UBC-Okanagan, the reassignment to Thompson Rivers University, and some other advancements. Especially UBC-O has attracted many Albertans, with about 1/4 as many new undergrads coming from Alberta as from BC, versus about 1/10 as many that head to UBC Vancouver. Scaling up Albertans heading to UBC-O might account for up to one-third of the increase.

(Figures 15 & 16, UBC Enrolment Report 2020/21)

There is a saying that ‘people work in Alberta and play in BC’, and this is supported by highway patterns and recreational properties. For Alberta families who regularly travel to BC for recreation, it may be an easy transition to enroll in universities there.