If you pay attention to UK higher education, you will know that yesterday the long-awaited Augar Report (technically, the Post-18 Review of Education and Funding: Independent Panel Report, but its usually named after its chair, Philip Augar). It’s a big study – over 200 fairly densely-argued pages – and since I’ve spent the entire day in meetings in Washington DC I haven’t had the time to peruse the document closely and my commentary is based to a considerable degree on secondary analysis (I am particularly indebted to the talented tribe of warrior policy nerds at WonkHE who have done a tremendous job on this).

The report covers a lot of topics, but the two most important are the perennial topic of tuition fees/students aid and the question of how to treat higher education (universities, basically) and further education (colleges, basically) more consistently and holistically. The second topic is probably the more important, but since tuition is central the policy discourse (in England as elsewhere), it’s the former that has been pushing all the headlines in the UK, so we’ll deal with that one first.

What you may have seen over the past day or so is a headline that says the report recommends cutting the “headline” tuition fee from £9,250 to £7,500. Superficially, this sounds like good news for students, but not if you actually understand the UK system. If you’ll allow me a quick digression here: the UK does not currently have tuition fees in the sense that anyone outside England understands them. When a student enrols, the government issues a voucher to an institution equivalent to what that institution, for reasons that are not entirely clear, calls a “fee”. After a student graduates, the student is subject to a graduate tax of 9% on income over £25,000 (about C$42,000), by which means the government tries to recoup the tuition fee. Students are then required to pay this until they have paid back i) whatever “fees” they have accrued plus ii) any student loans they may have taken plus iii) interest, or until 30 years have elapsed, whichever comes first. (Students – or usually their parents – do have the option of pre-paying fees and avoiding the interest but they forego the possibility of forgiveness 35 years out, so most don’t pre-pay). And while this policy has only been in place since 2012 and we don’t know for certain how much will be repaid, the best estimates right now are that he vast majority of students will not pay back in full and that as much as half the value of the fees and loans will never be recovered.

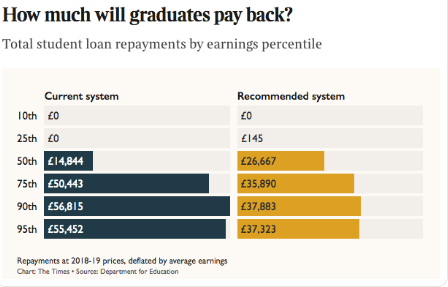

So – when someone says tuition fees in England will go down, what this means is the fraction of students who already pay off their loans – that is, the most successful – will pay less. Most students will not see a big change and many will see none at all, but universities will take it in the neck because they lose those pounds. Now technically, this isn’t quite what Augar did. He suggested the reduction in fees partly for reasons of access (which I think are pretty spurious: the number of students who are dissuaded from study at £9250 but not dissuaded at £7500 is infinitesimal), and partly because he wanted to give the government more control over which programs are going to be offered at universities. This he suggests doing by replacing universities’ lost revenue with an increased base grant – but on an aggregate, sector-wide basis (in the region of £3 billion, I think) rather than an individual student basis, and with a strong tilt towards expensive, STEM-programs and away from social science, humanities and – especially – creative arts programs (because God forbid we trust institutions to cross-subsidize internally on their own). The problem is that the UK is in the middle of a public spending review and literally no one believes that this recommendation will make it through the Treasury’s budgeting process: so the tuition/voucher cut will sail through but the grant increase will not and hence the true net effect of all this will likely resemble what happened in Ontario earlier this year when tuition fees were cut by 10%). Augar also suggested a clutch of other changes to student assistance which matter to students, if not to institutions. The first is the restoration of maintenance grants (eliminated in 2012) to help poorer students, which is an unmitigated plus. The other, slightly weirder set of changes, is to increase the loan repayment period to 40 years (thus giving more time to squeeze money from lower-income graduates) while at the same time capping the total repayment including interest at 1.2 times the amount borrowed which decreases the amountpaid by at least some of the top-income borrowers. The Times crunched the numbers and found that the main losers were median-income graduates while the main winners were top-income ones:

Now, as I said, Augar wasn’t all about fees and aid. Maybe the most interesting (and hopefully the most consequential) part of the report looked at the question of the types of skills being produced in the British economy. To both cut a long story short and simplify a bit, the report implied pretty strongly (and to my mind correctly) that the country as a whole was over-investing in universities and underinvesting in colleges, and recommended some increases in college funding as a step in that direction, along with making a raft of proposals to improve apprenticeships.

But maybe the most revolutionary thing about this report – and it is an excellent report, obviously based on meticulous research, a welcome change from the previous “big report” in UK higher ed (2010’s Browne Report) – was its mandate. The idea that all education for over-18s should be governed by a single overarching policy is more or less new in the UK, which has been resolute in keeping universities separate from the rest. There are various problems with some of the recommendations, and no doubt the implementation will fall some way short of ideal (recall that this is an advisory report rather than a government report and the UK government in all its current omnishambular glory may implement all, some or none of it).

Overall, though, it’s the kind of report any country or province should wish to have on a complex policy topic: both thoughtful and thorough. Give it a read and think how many provinces here in Canada could benefit from something of similar quality.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post