A couple of years ago in a blog post I noted a tendency among western academics to assume that the Western view of the university was the only possible one, and specifically that universities which existed in illiberal or autocratic settings were not “real” universities. At the time, I said:

There are other university traditions, not all of which require liberal democracy to flourish: Lord knows the continual ascent of Tsinghua, National University of Singapore and others in international rankings is evidence of that (of course, we’ve known that about the lack of a relationship between liberalism and Science for years – even sixty years ago, the Soviets were showing us how hard sciences could flourish even under totalitarian conditions). And so, when I hear people say, quite obviously with the best of intentions, that “academic freedom is a universal value in higher education” and ask that institutions be judged accordingly, I have to ask myself: is it that westerners want to impose their institutional values on others? Or is it rather that deep down, they do not believe that universities in illiberal countries are universities at all?

So, this debate has now started again thanks to University World News, which has recently been giving quite a lot of space to something called the Academic Freedom Index (AFI). The AFI was originally developed by a group of political scientists at the Varieties of Democracy (V-DEM) Institute at the University of Gothenburg. It was an interesting attempt to try to quantify academic freedom based on a set of indicators which covered i) freedom to research and teach, ii) freedom of academic exchange and dissemination, iii) institutional autonomy, iv) campus integrity (meaning, very roughly, freedom from the presence of security forces) and v) freedom of academic and cultural expression, which is kind of an overlap with i) and ii) but whatever. As is common practice among scholars in the “measuring various aspects of democracy business”, the V-DEM crew then proceeded to provide 2,000 or so local “experts” around the world (how they are identified and recruited is unclear) a codebook explaining what each of these indicators is meant to represent and ask them to rate the countries in which they live and work.

In addition to these expert-coded indicators, two “de jure” indicators were added: whether academic freedom is guaranteed under the national constitution and whether a jurisdiction has signed onto the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights without reservation or not. This suggests a continental European view of how rights come into existence and are protected; Canada would get nil points for academic freedom in the constitution, for instance, because by and large we have chosen to use collective bargaining as a tool instead. An over-reliance on de jure measurement can lead to absurdities if you take it too far. A 2017 article in Policy Reviews in Higher Education entitled “Measuring academic freedom in Europe: a criterion-referenced approach”, for instance, used such a methodology to arrive at the frankly absurd conclusion that Croatia enjoyed the highest level of academic freedom in Europe, Estonia the lowest and that universities in Hungary are freer than they are in the UK (yes, really). However, because the de jure stuff is not too prominent in the V-DEM work, it does not really produce any silly results.

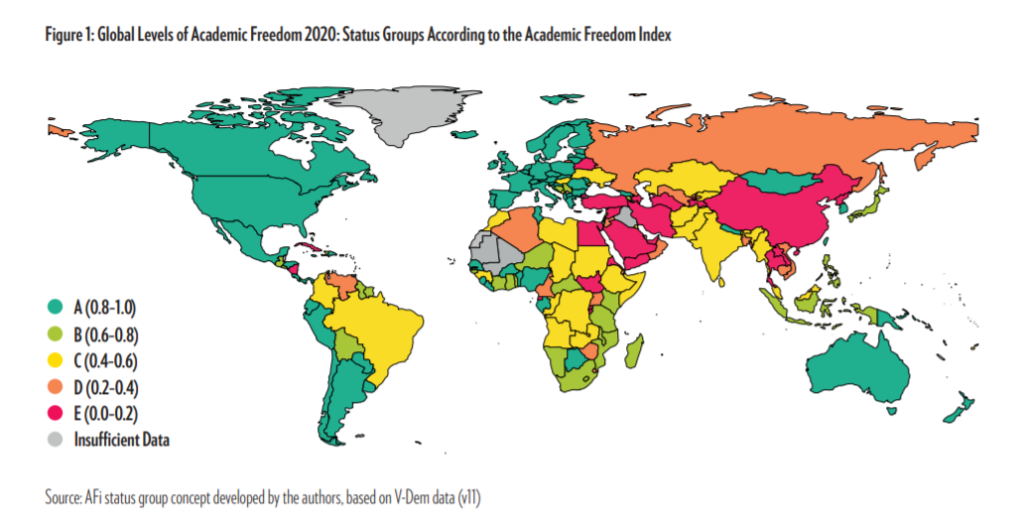

The V-DEM group published a follow-up report last month, in collaboration with the Global Public Policy Institute and the Scholars at Risk Network, showing how their methodology could quantify shifts in academic freedom in countries which shifting towards illiberalism (e.g. Poland, Turkey). They also published a list of scores of all nations, which I reproduce below. Basically, the OECD minus Japan and Hungary all get top marks. If you compare this to more general cross-national measures of freedom (such as those published annually by Freedom House), Latin America and India look a little bit worse than they usually do, Russia and East Africa looks a little better than they usually do (Mozambique absurdly so), and God knows what the folks coding Papua New Guinea and Mongolia were thinking. But overall, the message is clear: whether academic freedom is something which is universally desired, in practice, it is mostly confined to rich countries.

Of course, once you can quantify something, it’s only a matter of time before someone tries to apply it as a ranking. The authors themselves suggested as much in a UWN article last month, claiming that global university rankings are “complicit” in the erosion of academic freedom by not including it in their calculations. Then last week, Carsten Holz, of the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, went a step further in another UWN article by multiplying institutional scores from the Times Higher Ranking by national scores from the V-DEM project and – voila! – suddenly Chinese universities fall to the bottom of the ranking.

I get where Holz is coming from. As a western social scientist teaching in Hong Kong, it would be impossible not to be distressed by the changes currently taking place in the territory and what they will undoubtedly do to the academic environment at his institution and this article is a way of expressing a preference for one kind of academic environment over another. And what’s the harm in trying to deploy these kinds of arguments to protect your university?

Possibly nothing. But imagine for a moment that you are a scientist in China or Singapore or the Middle East or India and think how this kind of argument might appear to you. I would argue that says “only universities in the West can be ‘proper’ universities.” Whatever achievements universities in our countries produce – and many of them now do world-class science in many fields – they will never be allowed to claim co-equivalence with Western universities because of their country’s legal regimes. In fact, let me go a bit further: what this argument looks like is “just as universities from these countries are getting good at this kind of science, just as they start to rise in those rankings, jealous Westerners change the rules to favour a culturally-biased understanding of higher education so their institutions can stay at the top”. And sure, one could argue that academic freedom is a universal right not a western construct and so this isn’t really Westerners imposing their values on others – but that’s something someone with a colonialist mindset would say, isn’t it?

I could go on at quite some length about this, but I won’t. My point is simply this: one can argue for academic freedom whilst at the same time i) acknowledging that current academic norms in North America and Europe have never been universal and even in our own geographic contexts are barely a century old, and ii) avoid the insulting implication that over half the world lacks “proper” universities. Surely this is possible.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

I should think that we could square this circle rather easily by simply acknowledging that “world-class science” can be produced in many institutions that are not universities. We shouldn’t consider a Soviet research village, Xerox PARC, the Edison labs, Google or NASA to be universities, but we do respect their science.

In any case, invoking academic freedom like this seems a necessary exercise as part of the effort to define universities in any manner beyond the nominalist (i.e., a university is anything called that), or the empirical (a university is anything that looks like other universities). The real problem is that for decades we, in the west, have (with certain honourable exceptions) not developed a real definition of what constitutes a real university, as opposed to something just called that. Hence all the stupid rankings we have now, based on outputs or inputs, rather than on a real commitment to the life of the mind. And this rather shallow evasion of self-definition has led to a rendering of our societies more shallow, less critical, and less literate. It’s why the administrators of Laurentian think they can get by without a physics or philosophy department, or very many languages, and still bear the name of a university without shame.

Finally, I would note that while specific definitions of academic freedom do have a relatively recent history, the idea of pursuing knowledge as an end in itself really is as old as the university, at least if we’re to take “university” as an invocation of the western tradition of universities. The AAUP developed its definitions in responses to threats to an important principle, one which antedates the AAUP definition. Medieval universities received certain rights, often from competing jurisdictions, and were therefore independent. Moreover, they were not reducible to an instrumental role, for either the state or the church: Frederick II’s attempt to create a university under state power to produce courtiers for himself failed outright, despite the heavy-handed support of a bona fide tyrant. The bishops of Paris issued approximately sixteen lists of theses that were condemned. Had the medieval University of Paris simply been a priest-school, its faculty would never have developed heretical thoughts. While specific statements of academic freedom are fairly new, an institution that would not even wish to constitute a safe (some would say “privileged”) place for the life of the mind, simply isn’t a university at all.

(Sorry to go on so long; the things I do to avoid marking!)