So, yesterday saw the release of the first results from the Survey of Adult Skills, a product of the OECD’s Programme for International Assessment of Adult Competencies. This survey is meant to examine how adults from different countries fare on a set of tests measuring cognitive and workplace skills, such as literacy, numeracy, and ICT skills; perhaps somewhat controversially, some of the OECD’s own employees are referring to it as a “ranking” (though, honestly, that does them a grave disservice). Additionally, Statistics Canada did a seriously massive oversample, which allows us to make comparisons not only between provinces and territories (to my knowledge, this is the first time anyone’s gone to the trouble of getting representative data in Nunavut), but also between immigrants and non-immigrants, and aboriginals and mainstream Canadians.

Fun, huh? So much fun it’s going to take me the rest of the week to walk you through all the goodies in here. Let’s begin.

Most of the media coverage is going to be on the “horse-race” aspects of the survey – who came top, across the entire population – so that’s a good place to start. The answer is: Japan for literacy and numeracy, Sweden for ICT skills. Canada is middle of the pack on numeracy and literacy, and slightly above average on ICT. These Canadian results also hold even when we narrow the age-range down to 16-24 year-olds, which is more than passing strange, since these are the same youth who’ve been getting such fantastic PISA scores for the last few years. Most national PIAAC and PISA scores correlate pretty well, so why the difference for Canada? Differences in sampling, maybe? It’s a mystery which deserves to be resolved quickly.

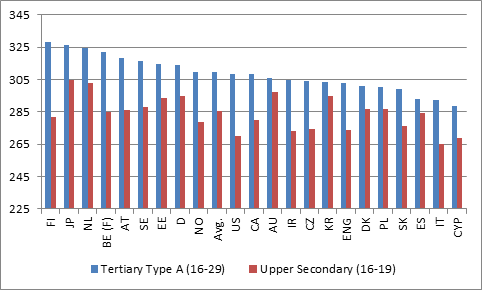

But here’s the stuff that grabbed my attention: national literacy scores among young graduates, by level of education. The scores for secondary school graduates are for 16-19 year-olds only; the scores for university graduates are for 16-29 year olds. Note that scores are out of 500, with 7 points being equivalent (allegedly) to one extra year of schooling.

Figure 1: PIAAC scores by Country and Level of Education

Eyeball that carefully. Japanese high school graduates (red bars) have higher literacy levels than university graduates (blue bars) in England, Denmark, Poland, Italy, and Spain. Think about that. If you were a university rector in one of those countries, what do you think you’d be saying to your higher education minister right about now?

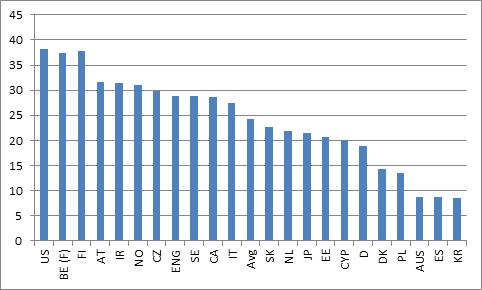

Another way to look at this data is to look at “value added” by higher education systems by looking at the differences between scores for recent university or college (technically, tertiary non-university, always a tricky category) graduates, and those for secondary graduates. Figure 2 shows the differentials for universities:

Figure 2: Difference in PIAAC Scores Between University (Tertiary A) and High School Graduates

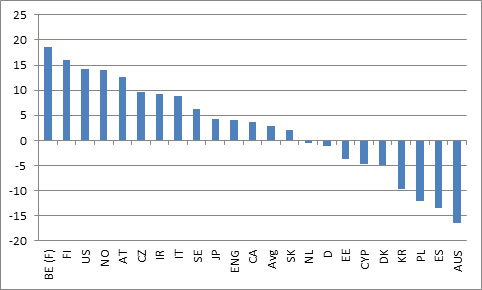

And figure 3 shows them for tertiary non-universities (Tertiary B):

Figure 3: Difference in PIAAC Scores Between “Tertiary Non-University (Tertiary B) and High School Graduates

There’s an awful lot one could say about all this. But for me it boils down to: 1) the fact that so many countries’ Tertiary B value-adds are negative is a bit scary; 2) The Americans, Finns, and Belgians (the Flemish ones, anyway) all have really good value-add results across their whole tertiary systems; 3) the Australians and Koreans appear to have absolutely god-awful value-add results across their whole tertiary systems; and, 4) Canada is just… middle-of-the-pack. Not bad, but probably not where we should be, given how much higher-than-average our expenditures on higher education are.

More tomorrow.

14 Responses

Do the blue bars in Figure 1 (16- to 19-year-old high school grads) include current university and college students?

I would assume so.

Value add? Isn’t there a large selection effect going on there?

I don’t know about “large”, but presumably there will be selection effects, yes.

Perhaps the university value added is not that great…maybe the most literate kids simply choose to attend university.

This is almost certainly true, which makes you think that in fact in some countries the value-add might be very close to zero.

The US and Canada value added may look better because we draw strong high school students from around the world.

Yes, but they don;t always stay. If they don’t stay, they;re not in the sample.

Interesting stuff. It makes me wonder what specific competencies were measured, and by what means. No time to read the report right now, but maybe you could mention this. Assessing literacy across multiple languages seems especially complex; are we sure the results are commensurate? Are other readings of the data and comparisons across countries and cultures supported when that factor is considered?

Hi Ryan. I;m not an expert so I would surely mess up the description here. Pages 60 to 90 (IIRC) in the report give you a sense of the kinds of questions asked ans skills measured. As for linguistic equality, that;s an excellent question. Not being a psychometrician I have absolutely no idea how they do it, but it;s not something new – various international tests including PISA have been coming up with these equivalencies for a couple of decades and I think by now they;re getting pretty good at it (let’s hope, anyway).

I don’t think we can say that the Tertiary B value-adds are negative from this data — many Tertiary-B attendees are a subsample of the high school grads, likely scoring lower than average in high school. Then in Tertiary B many would not be studying to improve some of the skills tested in Tertiary B, but learning other skills (cooking, pipefitting, caretaking, haircutting, etc.) — apples and oranges?

Hi Cynthia. yes, clearly, something of that nature is going on – but I’m a bit skeptical that’s the whole story. It’s rare that students *much* below the average end up in tertiary B. And they still should be progressing somewhat in skills from year to year (OECD estimates one year of schooling = 7 points on their scale). So to me it;s still surprising that anyone is negative. Shouldn’t be happening.