There’s a line I hear every once in awhile from profs (mainly, but not exclusively, in the humanities) saying something to the effect of: their job is not to prepare students for the world of work; rather, they want to prepare students’ minds to be critical thinkers or better citizens, or something like that. Actually, it’s usually phrased less delicately, like: “I’m not preparing kids to be cannon fodder for the knowledge economy”; “I don’t give a damn what employers think, I only care about my students”, etc., etc.

Now, this is admirable, in a way. Universities certainly shouldn’t be training people for specific jobs (and to be fair, I don’t think there are that many people arguing this). Even where universities are offering professional education, as a rule they should be training people for diverse careers in a profession, not a particular job.

But in a way, it’s also kind of a silly position to take, for two reasons:

First: It’s not either/or. The insistence that education either has to be “for” the labour market or “for” personal betterment/critical thinking is laughable. For instance, most of the skills that matter for the humanities – the ability to critically appraise documents and arguments, appreciating complex chains of causation, writing clearly and effectively – are also pretty important in the world of work. Surely it is not beyond the wit of universities to design programs fit for multiple purposes. So why is there such a tendency within the academy to strut and preen and claim that never the two shall be one?

Second: If you really do want to put the student first, then employability skills need to be front and centre. Getting better jobs is really why students are there – and that’s been the case for a very long time.

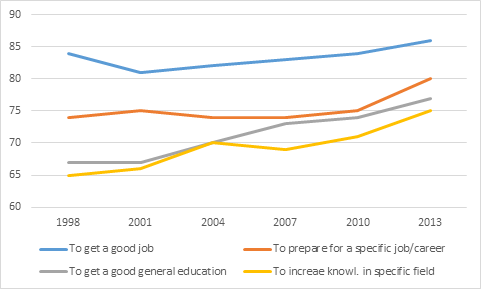

Every three years, since 1998, the Canadian Undergraduate Survey Consortium (CUSC) has been asking freshman why they decided to attend university. The top two answers have always been “to get a better job” or “to train for a specific job or career”. The next two answers have always been “to get a good general education” and “to gain knowledge in a certain field” (See? Students don’t think it’s either/or). The humanities aren’t exempt from this: 76% of students in these fields say “getting a good job” is “very important” to them.

Figure 1: Importance of Various Factors in First-Year Canadian Students’ Decision to Attend University, 1998-2013 (Percentage Indicating Each Factor is “Very Important”)

Now, if you actually drill down to what the single most important factor is, the results are even starker. In 2013, fully 68% picked “getting a good job” or “preparing for a career” as the most important reason to attend university; only 16% picked “increasing knowledge in a specific field” or “getting a good general education”. That’s not new, either: in 2001 it was 65% and 16%, respectively.

So while it’s legitimate to want to ignore the views of employers (especially in an era when employers are getting simultaneously pushier about wanting job-ready graduates, and stingier with the training dollars), it’s not legitimate to say that higher education shouldn’t be concerned with employability and the labour market.

It’s not for the companies – it’s for the students. It’s what they want. It’s what they think they’re paying for. It’s what they deserve.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

They certainly don’t deserve to be kept ignorant of everything that doesn’t lead them to a better job, so we must continue to stress the full human development provided by a true education. This is especially important in the face of an entire society apparently bent on reducing education to job training, of which your 68% of students are representatives.

The reason that the choice between education and training is not either/or, is that the goals of a liberal education — critical thinking, creativity, high level literacy — can’t be approached directly. Rather than taking a course in something called “Critical Thinking 101” or (worse) “Critical Thinking for Business Majors” students learn to be critical thinkers by being made to think critically about (say) Tolstoy’s War and Peace or Byzantine art. They’ll learn a high level of literacy trying to express their views on such demanding subjects in structured essays. And they’ll certainly succeed better than those who took some kind of memo-writing workshop.

To make the link from the course material to the needs of the workplace is, in fact, to fail both. Only by maintaining the integrity of education in the face of calls for its ruin by training do we form critical minds, nurture citizenship, expand imaginations, and, yes, improve employability.

Agree completely you can;t approach the goals directly. But one does, I think, need to approach the assessment of progress towards those goals directly – something we’re not very good at right now.

And while I agree essays are useful for developing critical thinking, I think you’ll find the inability to be concise is a major problem on the whole employability thing. Mixing essay assignments with more concise forms of writing would be useful, too (I remember a friend doing quite a good “Memo to the Emperor” on strategic options following the Opium War, for instance).

Assessment is another matter, perhaps for another post. A good essay is fairly concise — in style, if not in length — but you’re right that this isn’t always what students are taught. It strikes me as a good example, however, of what we agree on: if students aren’t free to explore, they won’t uncover the sort of clear thesis that they can express in a neat argument. If we start by telling them to be concise, we’ll end up with a lot of shallow readings and obvious claims.