Lost in all the back-to-school period excitement was the release of Ontario college enrollment data for 2018-19. The recency of this Ontario data is fantastic, especially given that Statscan is two full years behind (the best data available on students nationally right now is 2016-17, because Ottawa fundamentally does not care about student data). These are well worth a look because there are some wild things in there, especially if we look at students by “source,” which is a weird mixture of identity and geography.

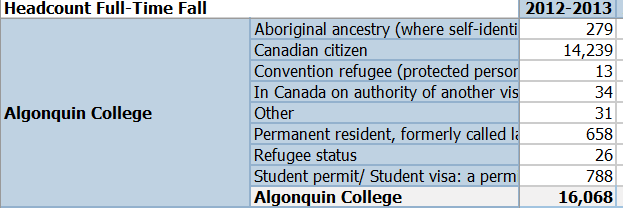

Ontario colleges ask some perplexing questions about identity. For instance, this is the way Algonquin College does it (picked because they are first alphabetically, not because they are an outlier):

Figure 1: How Ontario Colleges *Actually* Describe Their Student Body

Got that? “Aboriginal ancestry” and “Canadian citizens” are mutually exclusive categories. Oy. Also: ancestry? Who asks an ancestry question? Surely what matters is identity. Deeply weird. Colleges of Ontario (or Government of Ontario, if you’re the one responsible), please do better.

Anyways, if you add up all the institutional lines for aboriginal ancestry/identity/ whatever, what you see is a deeply disturbing picture; namely, that the numbers of self-identified aboriginal students have fallen by 24% of over the past three years.

Figure 2: Number of Self-identified Aboriginal Students in Ontario, 2012-13 to 2018-19

What explains this? One possibility is that it is a knock-on effect from the passage of the Ontario Child Care Modernization Act in 2014. With the breathtaking cynicism that only a government in its fourth term can muster, this act contained a Schedule which modified the Training Colleges and Universities Act in such a way as to allow the provincial government to seize more or less any piece of data on students it felt like, including self-disclosures on ethnic identity, gender, sexuality, etc. At the time, many people suggested this would reduce self-disclosures, but these claims were ignored, in the spirit of the screw you, we can do what we want attitude that prevailed in the late Wynne years. I cannot, obviously, prove a connection, but the coincidence in timing is at least suggestive.

There is even more interesting stuff on the international side. Figure 3 shows headcount enrolments in Ontario Colleges, counting visa students as “international” and everyone else as “domestic”. Basically, domestic enrolments are rock-steady over the past six years, while international enrolments have increased four-fold, with most of that change happening in the last two years.

Figure 3: Domestic vs. International Enrolment at Ontario Colleges: 2012-13 to 2018-19

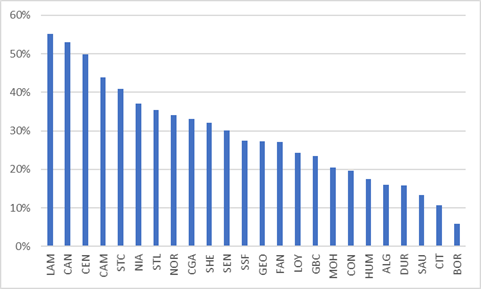

In addition to the 72,300 international students, there are 8-9,000 students whose origin is listed as “unknown” and are a variety of hints in the database that suggest these students – concentrated in six specific institutions – are mostly international students. If we include these students in the international total, we find that the system is now 29.9% international students. As Figure 4 shows, not only do 18 out of 24 institutions have student bodies which are more than 20% international but there are three -Lambton, Canadore, and Centennial – where the percentage is over 50%.

Figure 4: International Students as a Percentage of Total, by College

Now you may well be asking yourself: Lambton? Canadore? In Sarnia and North Bay? What’s going on? Shouldn’t we have noticed if the proportion of international students suddenly rose by a factor of 8x or 10x? Well, yes. But these enrolment increases aren’t happening in Sarnia or North Bay. They are happening in Toronto. As I noted back here, a number of non-GTA colleges (Cambrian, Canadore, Lambton, Northern, St. Clair and St. Lawrence) have opened up “partnership agreements” with private vocational colleges in the GTA. Under these agreements, international students pay these non-GTA colleges, who then assign the students to GTA based private colleges. The private colleges then receive a per-student fee for providing a curriculum designed by the public college. The private college’s fee is lower that the tuition fee the student paid, and the public college pockets the difference.

In 2017, David Trick – then a consultant, now interim head of the Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario – wrote a report on these colleges that was unusually damning. These partner colleges were described as not serving “an important public purpose and are an inefficient way to provide needed revenue for colleges”, and the partnerships as a whole were seen as posing “risks that are inherently difficult to manage.” Trick recommended closing these programs and providing new funding to smaller colleges. The Wynne government did the first bit, ordering institutions to halt intake after 2018, but not the second bit. It is now 2019, and these colleges are still in operation, which means either institutions are flouting the law, or the Ford government quietly countermanded the Wynne cease-and-desist order (as far as I know there is no public notice to this effect).

Either way, it’s a story that needs follow up.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post