Most of what we know about the Laurentian affair suggests that it is sui generis, but some people insist on turning it into an exemplar of broader trend: not so much a “who’s next” as a “there but for the grace of God go all of us” (or, as a recent podcast had it: is Laurentian the “canary in the nickel mine”?). Basically, this argument suggests that Laurentian is not really at fault, but rather a victim of “the Ontario funding model.” It’s a notion prevalent among those who want to claim underfunding is a problem (it is, but not in the way people think), and super-prevalent among those who want to blame the current Conservative government for pretty much every ill under the sun.

But is it true? Let’s find out.

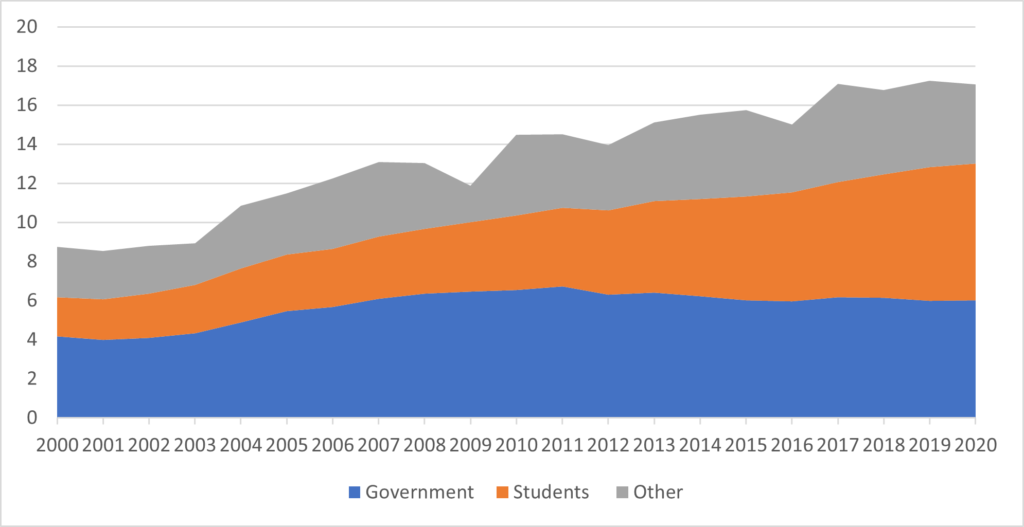

First, let’s look at what’s happened to university financing in Ontario. Figure 1 is a 20-year history of university income sources. Three facts pop out here. The first is that total institutional income nearly doubled between 2003 and 2019. You’d think this fact might get mentioned when we talk about “austerity” and “underfunding”, but whatever. The second is that government support has been tailing off for over a decade. The third is that income from students is more important than it was 20 years ago, and that is thanks in no small measure to the expansion of international student enrolment.

Figure 1: Institutional Income by Source, Ontario Universities, 2000-2020, in billions of constant $2020.

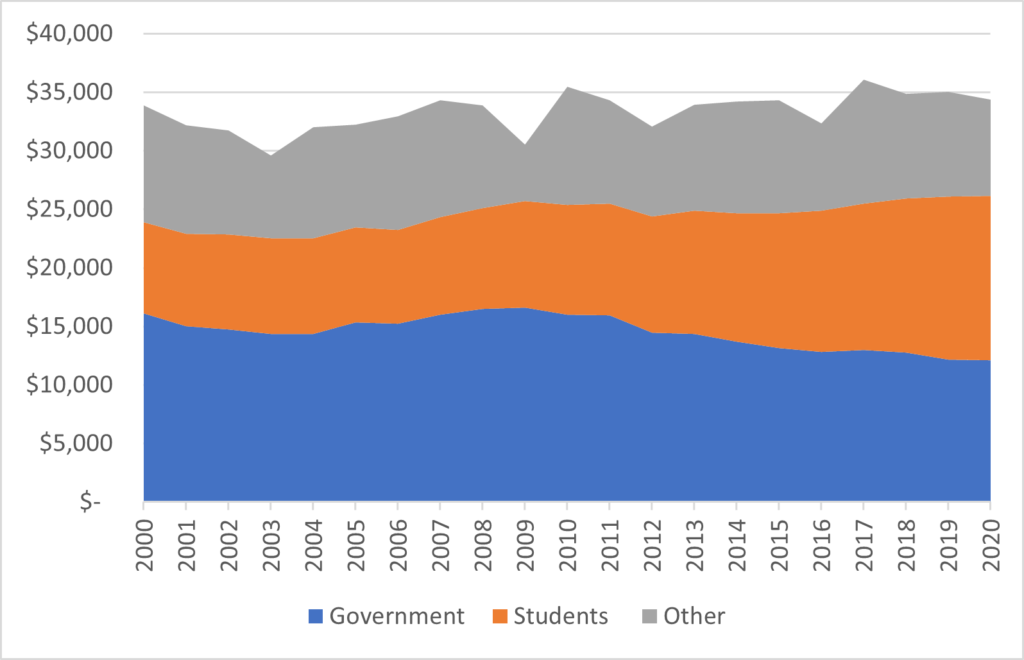

Of course, part of what this big run-up in funding has paid for is a massive expansion of places. Total full-time equivalent enrolment is up 92% over 2000. You’d think we might mention this whenever we talk about accessibility, but whatever. Figure 2 puts all those income figures in per-student terms. There are two main takeaways. First, unlike most systems that double in size over such a short space of time, there have been effectively no economies of scale achieved: total $ per student has stayed roughly constant over twenty years. And second, it’s apparent how student fees (again, mainly international students since about 2013) have replaced public funding since 2009.

Figure 2: Per-student Institutional Income by Source, Ontario Universities, 2000-2020, in constant $2020.

So the “Ontario model”, if one can call it that, is one where governments – primarily Liberal but also Conservative – have realized that foreign tuition fees substitute for domestic tax dollars as a way to keep public universities afloat. And so far, on aggregate, it works.

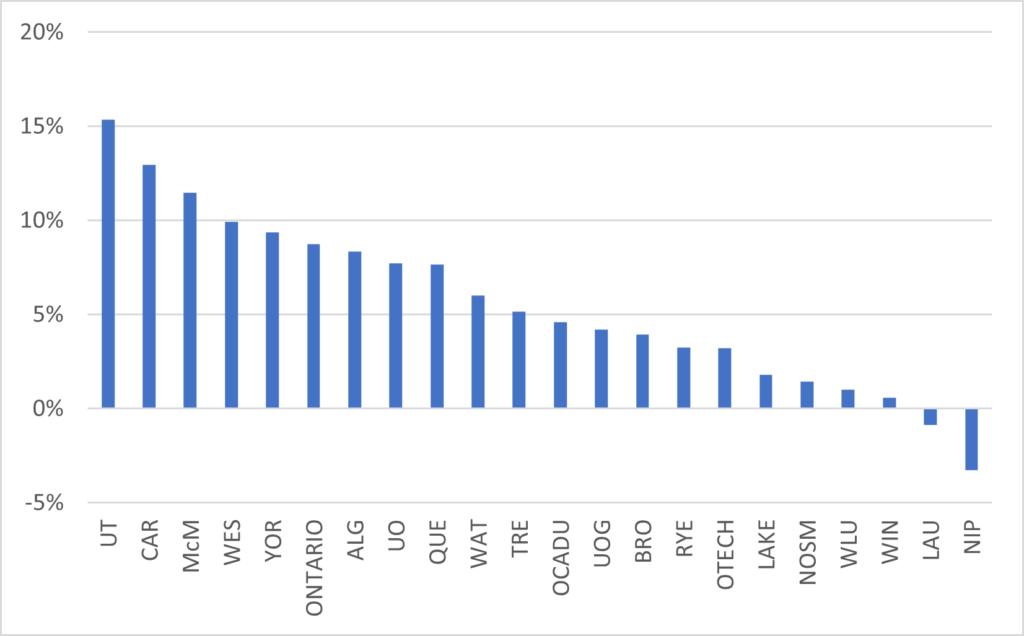

The question is whether it can be made to work for all institutions. By and large, it does. Figure 3 shows the average net surplus of all Ontario universities for the last three years. Collectively, revenues have exceeded expenses by almost 9%, or roughly 3.6 billion dollars. True, about 1.4 billion or 40% of that comes just from the University of Toronto (hey U of T pals: use some of that to pay your grad students more, it’s a worthwhile investment). But even excluding U of T, province wide the surplus averages 7% and only two institutions – Nipissing and Laurentian, lost money over the period 2017-18 to 2019-20 (OCAD U would have been in the loss column as well had it not sold one of its properties on Richmond Street).

Figure 3: Aggregate net surplus/deficit, Ontario Universities as a Percentage of Total Expenditures, 2017-18 to 2019-20

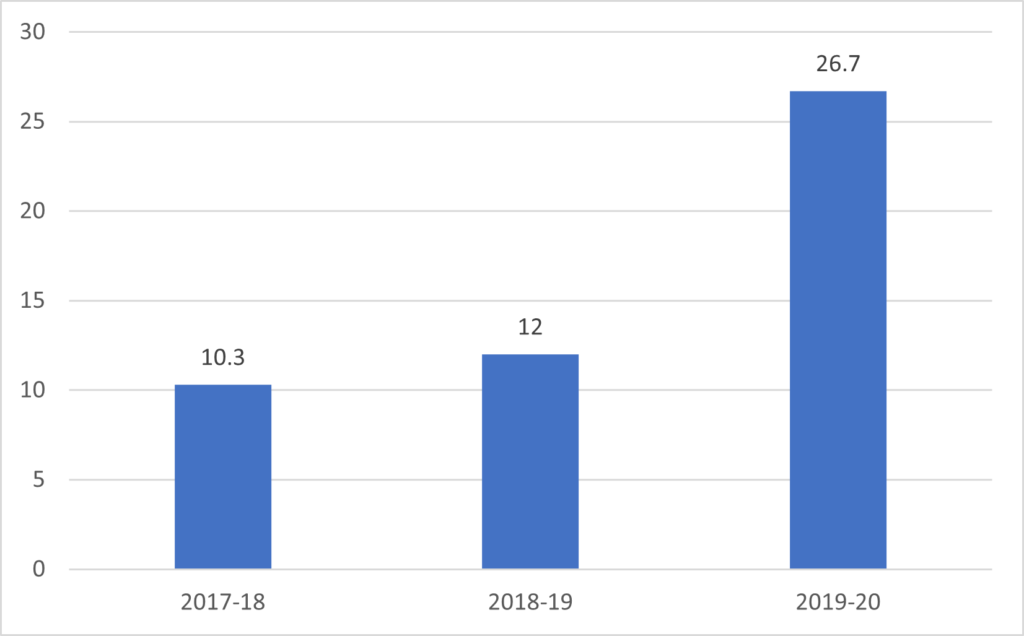

It mostly works: it just doesn’t for Nipissing and Laurentian. The problems of these two campuses sometimes leads to suggestions that the issue is recruiting students into northern campuses. But you can’t entirely blame “northern-ness” because Algoma and Lakehead are both doing just fine. Figure 4 shows Algoma’s revenue from student fees. Clearly, somebody has figured out how to get international students in the door.

Figure 4: Algoma Student Fee Revenue, 2017-18 to 2019-20, in Millions

Now you might say, but doesn’t Algoma have a campus in Brampton, and might that not be where the students go instead of Sault Ste. Marie? It is possible, but I can’t find any data which would prove this one way or the other. Even if it is true, Nipissing also has a GTA presence and there’s nothing preventing Laurentian from doing the same.

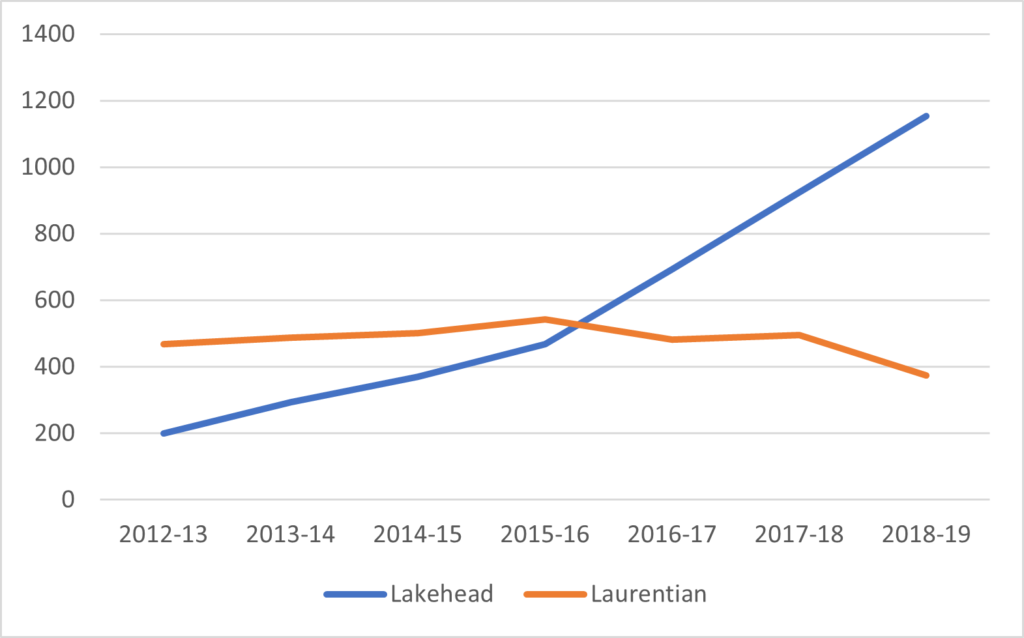

Figure 5 compares the performance of Thunder Bay’s Lakehead and Sudbury’s Laurentian in terms of enrolling international students. It should speak for itself.

Figure 5: International student enrolment, Lakehead vs. Laurentian, 2012-13 to 2018-19

I suppose you could say that the sector is systemically vulnerable to a loss of international students, but as far as anyone can tell that hasn’t happened yet, even with the pandemic (data isn’t available across the sector yet and probably won’t be until Fall 2022 because this is not a serious country when it comes to data), but Toronto, York and Ottawa are all reporting increases in international students for 2020-21, so I suspect that system-wide the model is stable, at least until Xi Jinping goes full neo-Maoist autarchy and cuts off the supply of students from the People’s Republic.

Ontario does have a distinct financing model. Of course, in that peculiarly passive-aggressive Canadian way, it has never been explicitly presented as an actual model; rather it is a set of rules of internalized by insiders but never explained to the public. The problem from a macro perspective is not that the system is untenable – in fact most universities are doing fine – but that at least one university – Laurentian – never really got the message.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

I’m trying to sort out Ontario’s double cohort in your first graph. I see the sharp increase in the “other” category, but the student and government categories seem more smooth, whereas I would have expected a lot more funding entering the system. Was the increase in the first year students not sufficiently large to impact the overall funding contributions? I also don’t see a significant drop after the cohort was done. Got any insights?

The drop in foreign student enrollment in 2017-18 at Lautrentian may have been Saudi student withdrawal. At the time I was working at the school and it was a cause of major concern.

Trump’s immigration policy may account for the spike in international students in Canads. This number may flstten as US immigration policy opens up under Biden.

Laurentian and Nippissing may indeed have problems. But this hardly accounts for why the Council of Ontario Universities has claimed that Ontario universities are facing a $1 billion in Covid-19 related costs and revenue shortfalls.

But the failure of the student debt/make international student model can already be clearly seen in Australia and the United States. In both countries – with similar levels of public underfunding – layoffs over the past year account for appr. 13 percent of the total PSE sector. In Australia, this has led to 17,000 layoffs, in the US more than 650,000.

Similarly, it is clear that Covid-19 has not only affected Ontario. BC universities and colleges are running $180 million dollar deficits; NB more than $10 million. In both Ontario and NB, universities have requested emergency stabilization funding.

No European university system – that I know of – faces such problems, and none have thought it wise to start gutting their universities in the midst of a pandemic and facing a global climate crisis.

From a macro-perspective, I would say it is pretty clear that there are major problems with Canada’s funding system and a major public overhaul is required.