A few weeks ago, the economist Armine Yalnizyan penned a really good piece for The Star. It examined epoch-defining shift in “developed” economies from a world in which labour is plentiful and capital is in short supply, to one in which capital is plentiful and the competition is for labour. This will have profound effects on higher education, which I don’t think many in the sector have absorbed.

The upshot is this: we are going into a period where labour markets are going to be permanently tighter, right across the board. This isn’t about any “Great Resignation.” The Great Resignation is basically nonsense – there’s no Canadian data to suggest it is happening and even in the US, the data suggest that it is almost entirely confined to people in low-wage jobs. It’s a meaningless buzzword being pushed by the major consultant set for reasons which I am sure make sense to them, but the rest of us can safely ignore.

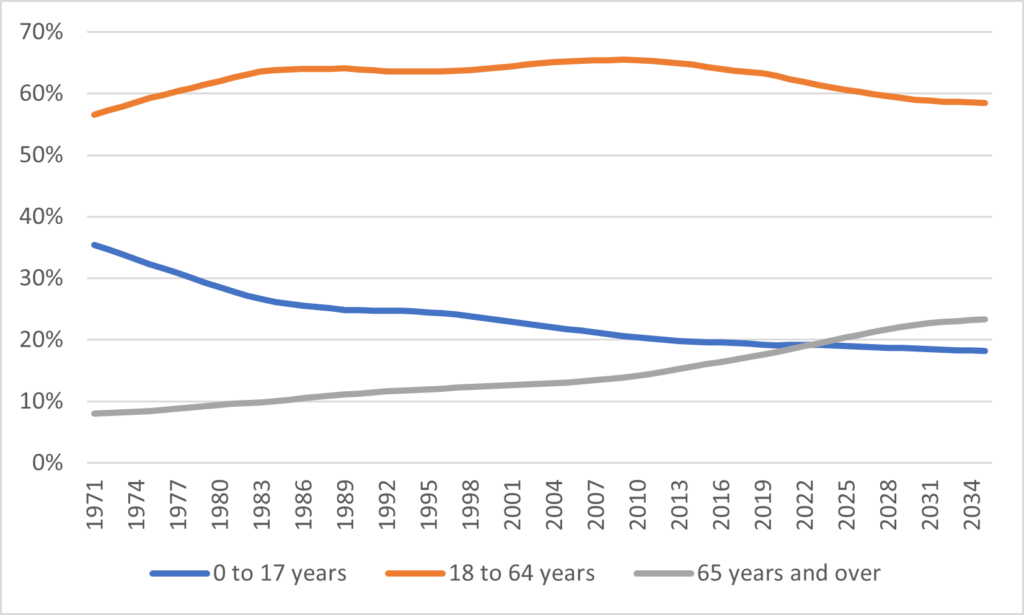

No, it’s simple demographics. The overall population continues to increase, which means aggregate demand is increasing, while at the same, the proportion of the population which is of working age is declining. That proportion was 64-65% from the early 1980s until 2018. It is currently falling, and quickly. This year it is just over 62%, heading to 60% by 2026 and bottoming out around 58% in the mid-2030s. This is basically a reversal of the demographic dividend that occurred when the baby boomers entered the labour market. Wages will increase, probably across the board, but growth will also probably slow.

Figure 1: Age Composition of Canadians, 1971-2035

Now, when wages rise, some in higher education will no doubt be quick to see a rise in graduate incomes and make various claims that “look, see, university/college pays”. They might even start to make arguments for tuition rises to match the increases in salaries. But this would be a mistake. The private value of higher education is related to the difference between university/college graduate incomes and high school graduate incomes. In a tight labour market, if all wages are rising, that difference probably isn’t expanding. In fact, it may even be shrinking.

Why might that be? Well, because one of the main things that happens in a labour shortage is employers don’t have the luxury of demanding lots of additional qualifications for a job. That includes educational qualifications: some jobs which “require” master’s degrees may start to open up to bachelor’s graduate, and so forth. That would tend to lead to faster wage growth at lower levels of education.

And that in turn would have some important impacts on the demand for higher education. According to standard human capital theory, a rise in the price of high-school educated labour has the same dampening effect on demand for higher education as a rise in tuition. And we have some fairly clear empirical evidence that this is the case, at least for men. Just go back about ten years to boom-time Alberta and see what skyrocketing wages for unskilled or semi-skilled labour did for post-secondary participation rates. When you can make $25/hour stacking boxes, why crack the books?

Even where people choose to attend post-secondary education, the effect of higher opportunity costs is going to affect the kinds of educational opportunities people are seeking. Students will be looking for shorter-times to completion, thus perhaps reversing the long drift from 3-year to 4-year degrees. They will be more likely to want programs which don’t require long commutes, thus perhaps increasing demand for online and hybrid learning. They will want shorter master’s degree or perhaps even disaggregated ones made up of micro-credentials. PhDs? You had better believe those will need to get shorter (if European universities can get students through doctorates in three years, why can’t we?)

I want to be clear about this: I am not saying all degrees will be shorter in a world of labour scarcity. I am saying that demand for shorter credentials will grow. Some institutions will choose to meet that new demand, while others will try to stick to their current markets and offerings. It’s not an all-or-nothing thing.

What I am saying, though, is that student demand is going to shift, and that shift will be towards degrees and programs that have smaller impacts on students’ earning opportunities. Smart institutions will bear this in mind when strategizing.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

“[I]f European universities can get students through doctorates in three years, why can’t we?”

In North American terms, the French Bac, three GCE A-levels, and German Abiturs don’t correspond to twelve years of study (like the OSSD)—they correspond to thirteen years of study (like the DEC) and are routinely and correctly treated as such by QC universities. Follow that up with total specialisation at the Bologna bachelor’s and master’s level—nominally 3+2 years, but that’s a theoretical ideal, and everyone in Europe knows it—and you get a future doctorand who’s already completed all the graduate-level coursework they’ll ever need.

BTW, *four* years instead of three is increasingly becoming the norm at elite European PhD programs, at least in STEM.

Given your thesis that students will want shorter stays in post-secondary, I would think this would pose a threat to co-op programs which are experiencing such rapid growth right now. Students perceive that co-op is a fast track to a career that pays well. If they don’t need co-op to get the same result… Other experiential programs that use the summers for the work experiences and don’t require extra time, may benefit.