As each year passes, it becomes harder to remember what exactly life was like before the internet. How did we communicate? How did we store and retrieve information? (A colleague recently commented on twitter that watching All the President’s Men today feels like an ad for Google because the first hour or so is just people looking through phone books). And, if you were in a specific technical field like higher education, how did you keep track of what was going on around the world? Well, the answer to that last question is “bulletins”. Bulletins were regular new roundups published usually monthly or quarterly. Everyone with news they wanted to share would give snippets to a central source and the central source would send a brochure it out to everyone on the distribution list. On paper.

A couple of years ago, as I was browsing through Amy’s Books in Amherst, NS (a real candidate for Canada’s most amazing used bookstore), I found a number of volumes of the International Association of Universities Bulletin from the 1950s and 1960s. So of course, I had to have them. And they are a treasure trove precisely as a window into what mattered in higher education 60 years ago.

Every issue of the Bulletin is bilingual (about half the articles in English and half in French) divided into nine or ten sections. There were sections on the IAU’s activities, those of UNESCO and those of other international organizations, all of which are boring and skippable. There was a section on “student life” was a collection of new stories about student services with – intriguingly – a lot of stuff about student mental health, which apparently was quite a big thing in the 50s before more or less dropping off the higher education policy agenda for five decades, a section on “university exchanges,” which was really a round-up of new international co-operation efforts, and a “publications” section which reviewed all the important new publications in higher ed from countries around the world (after 1958 the volume became large enough that only some were reviewed and the rest were consigned to a “publications received” list).

A section called “university development” kept everyone abreast of the creation of new universities, the opening of new university buildings, or the acquisition of exciting new equipment (e.g. “The University of Wisconsin has recently installed an electronic calculator, the first of its kind to any university, with a 20,000 digit memory” – 1956); by the 1960s, this section had stopped reporting news from individual institutions and was mainly reporting system-level news (a sign, presumably, of global massification). One of the fascinating recurring questions in this section in this period is the idea of “Television Universities” which were believed to be a way to alleviate the coming demand flood and yet sound awfully familiar to anyone who remembers the MOOC craze of 2011. The February 1960 issue, for instance, contained a story about Airborne Television Instruction in which “courses on video tape given by teachers recruited on a national basis will be televised from an aircraft some 20,000 feet over North-central Indiana. The estimated coverage of this “flying TV station will be an area 300-400 miles in diameter, reaching from Milwaukee to Detroit, Cincinnati and Louisville”

Another section called “current questions” reproduced speeches from higher education leaders around the globe. These, again, are dull, but the patterns of the subjects tackled are intriguing. In the late 1950s, there is a lot of concern about massification (how are we going to be able to afford to educate all these baby boomers?), the “two cultures” (this science stuff is all very well but how are we going to keep teaching classics?), and “higher education in the nuclear age” (which depending on context could mean “how will we train atomic physicists, that stuff is really expensive” or “how are we going to teach young people if they have all been reduced to radioactive cinders with a half-life of 700 million years?”). By the late 1960s, it mostly shifted to think-pieces (mostly in French) about “what do students really want”?

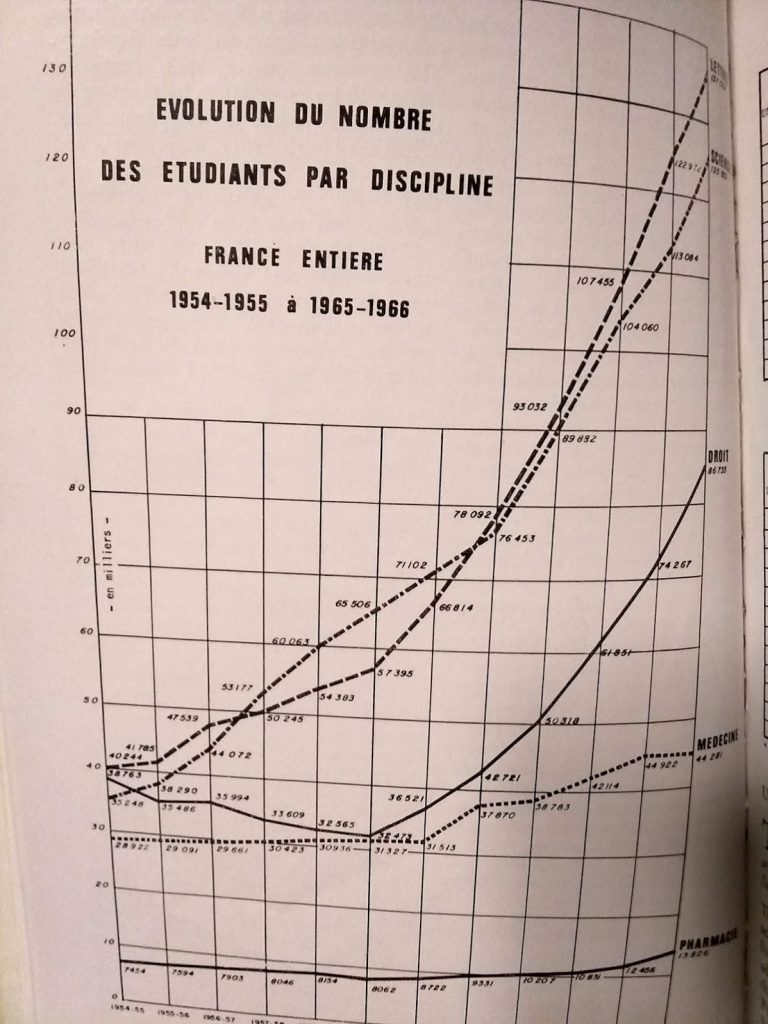

But you all know me: what I am really here for is the statistics. And the statistics pages are absolutely phenomenal. Primitive, in some ways, but phenomenal, nonetheless. Remember, it wasn’t until the mid-1960s that people found ways to actually start doing multi-national collections of statistics of education on a comparable basis. So mostly what you get in these pages are one-off reports from various countries about the latest educational statistics from each country. For the most part these are just reports on enrolments: below is one of the more detailed ones from 1968 in France.

And there is all kinds of stuff in there: surveys of professorial salaries from the United States in 1956 (about $5,000 per year in 1955, equivalent to $50,000 today), surveys of bursaries from France, quite excellent data on socio-economic background of students from Italy and Germany from 1955, which to my mind is of higher quality than anything Statscan puts out in our country today (because as I have said before, no one in Canada actually cares about access). Some of the stuff shows levels of transparency which would be unthinkable today, like a broad categorization of university expenditure in the Soviet Union for 1959, which I am fairly sure is unobtainable today for most of the successor republics.

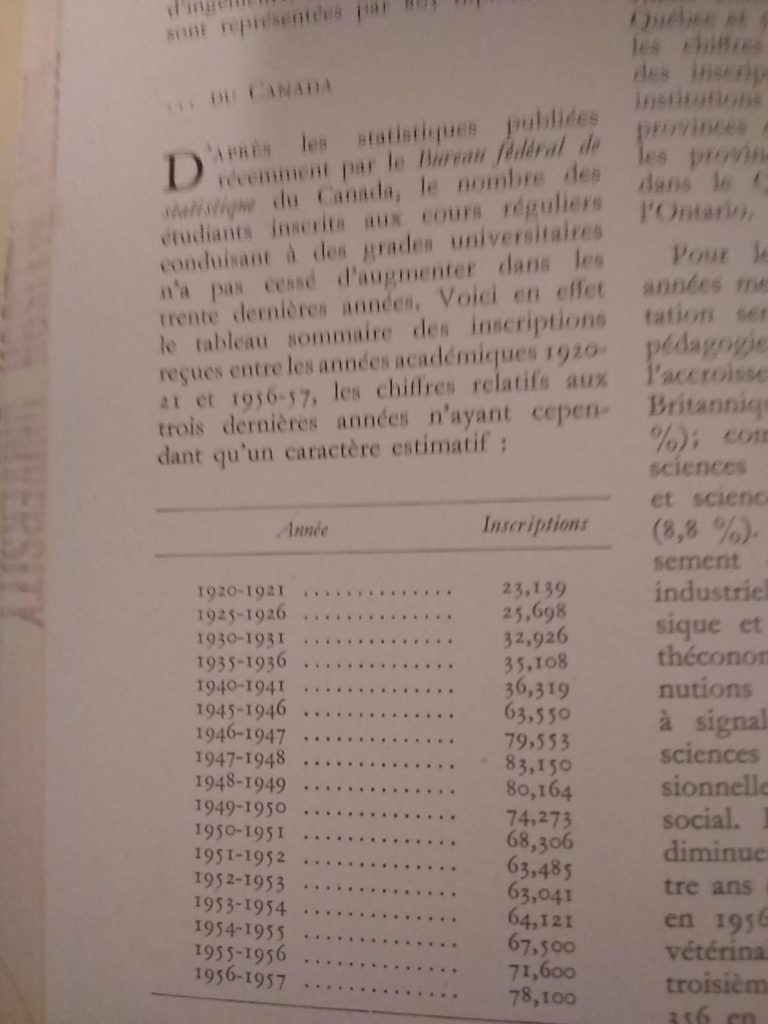

But amidst all these statistical Easter Eggs with all their magic detailed data, there lies the Canadian contribution to international education statistics, which apparently has always been as boring, crap and uninformative as it currently it is.

Have a good weekend.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post