If you just gauge public sentiment by twitter, it would seem the that CAQ’s policies on international and out-of-province students announced last Friday have a lot of support. Certainly, someone was quick to put together a few infographics – highly inaccurate ones, to be sure – for use as memes. But usually the arguments were phrased in terms of whatabbouteries: how expensive programs in Ontario were (usually based on cherry-picking the costs at, say, U of T Law and pretending they were the price of the entire sector), or on the relative investments made by Ontario and Quebec in minority language post-secondary education, which is somewhat more salient but pointedly ignores the investments in minority-language primary/secondary schools (where Ontario’s investments are significantly higher than Quebec’s).

The “we-pay-anglophone-institutions-too-much” is the key CAQ rationale for their new clawback on international student tuition fees. I understand Minister Déry described the re-imposition of a headtax on international students as correcting “the mistake” of the 2018 fee deregulation (the mistake being allowing in-demand universities to benefit financially in a way that less in-demand universities could not). Which is true if you think universities need to all have the same resources and individual university hustle in seeking new revenue is meaningless, but frankly that’s a pretty horrifying way to govern a system.

There’s another reason it’s problematic: not all universities have the same cost base. Anglophone universities in Quebec pay their staff on average about 9% more (in 2021-22, it was $146,193 vs. $134,674) than francophone ones do, partly because anglophone universities are more research intensive, but also because they are competing for a much more mobile talent pool in a much larger North American market. This fact is inconvenient, but it’s true.

But when it comes to international students, the rationale being offered by the CAQ is quite different and more dangerous. When differential fees were first introduced in 1996, the rationale was that Quebec taxpayers put in a lot of extra taxes in order keep tuition low, and they didn’t think it was right that people from other provinces could take advantage of this to pay less than they would pay if they stayed home. So, the out-of-province fee was set at the average of fees in the other nine provinces, which has an arguable logic to it (though Quebec ceased to use the other nine provinces as a peg about the time Ontario started reducing its fees and now the fee is about the 115-120% of fees in the other nine provinces).

What CAQ is putting forth as a principal, however, is that no citizen of another province should have any claim on public funding from the province of Quebec, because hey, ils ne sont pas nous, they never stay in the province anyway and screw them. There is a certain, mean, narrow logic here – “our taxes should go to our people”. But – here’s the scary part – what if every other province did that? With this as a rationale, we’re literally only steps away from the American system where every public university has a rate for in-state students, and one which is 200-400% higher for out-of-state students. Quickly, what look like a lot of individual “wins” for public finances start to look like one huge collective loss for students and student choice.

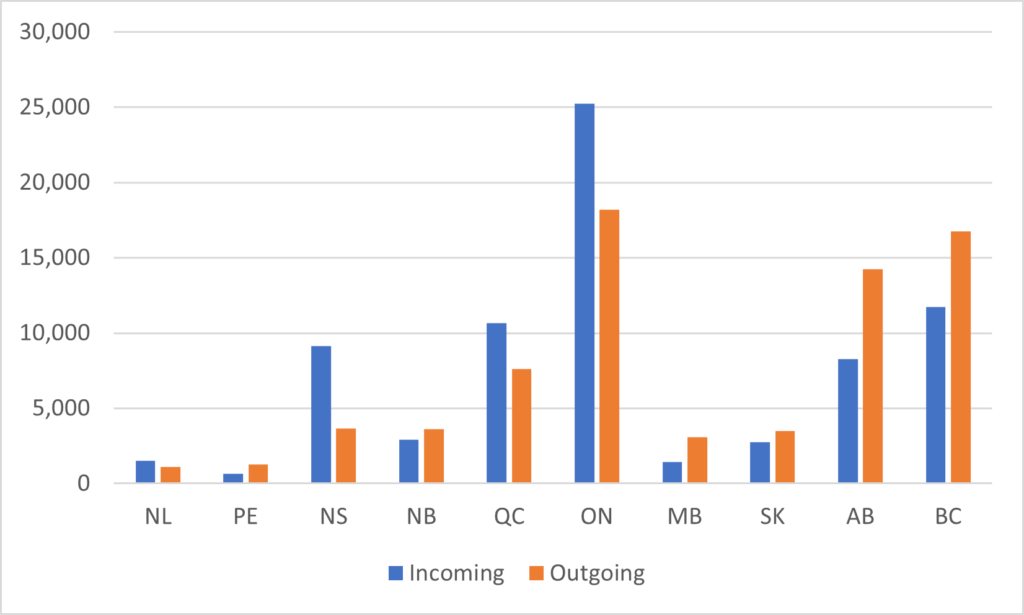

I mean, just for giggles, let’s take Ontario and Quebec. Yes, it’s true that 6,399 Ontario students went to Quebec to study and benefitted from QC taxpayer dollars. But guess what? 6,456 Quebec students went to Ontario and benefitted from ON taxpayer dollars! Now, what if the Ford government said that turnabout is fair play? Suddenly a) all the savings from the QC policy evaporate because QC must educate these students will stay home and consume PSE sector resources the same way the now-departed Ontario students did and b) we have a poorer, weaker nation because it’s so much harder for students to learn in other parts of the country. In other words, most of the economic rationale for the CAQ’s position disappears the instant other provinces decide to apply it as well.

Here’s the thing: once you set the issues of language apart, the financial “challenge” of interprovincial mobility is trivial in size. It’s true that about 8.5% of students in Canada move from one province to another. But the “net” movements – the ones that cause imbalances from financing “others” – is small. In fact, in total across Canada in 2020-21 there are only four provinces which were net importers of students (Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Quebec, and Ontario), and combined, their “net” number of importees is about 16,000 students – 1.5% of the national student body, or 2.2% of the student body in those specific four provinces.

So, let’s do a thought experiment: let’s say the feds meet the provinces halfway and said “we will pay every net importing province a $10,000 bounty for every net student they take in”. That would cost about $160 million per year, of which Quebec would receive about 20% (Nova Scotia would make out like a bandit, taking a little over a third of the pie). That would take care of the “we won’t pay a cent of our taxpayers’ money” argument. Do you think the CAQ would accept this solution?

My guess is no. Because for the CAQ, the money argument is a rationalization, not a rationale. They want fewer Canadian anglophones in Montreal, period (weirdly, the financial incentives they are setting up almost guarantee that these students will be replaced by English-speaking international students). And that’s all this is about.

But what’s pleasing to see is the sheer number of francophone Quebecers who are flat-out saying that the CAQ policy is terrible and short-sided. Both the Conseil du patronat and the Mayor of Montreal have come out publicly and strongly against the policy. Michel C. Auger had a hard-hitting column in La Presse (which has mostly been running pieces critical of the government on this issue). Even Le Devoir ran an op-ed saying the move would weaken Quebec. My own mailbox – which normally fills up with people telling me I have no idea what I am talking about whenever I write about Quebec – has this time been getting a pretty steady stream of emails from francophone university profs telling me how embarrassed they are by this move, how small-time and petty it makes Quebec look.

I don’t know how this story is going to end. But I’m less sure than I was a few days ago that this is a fait accompli. For the first time in a while, it seems like standing up to the CAQ for minority language rights might be a vote-winner (in the Montreal area at least).

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

One thing that I have not seen addressed in this analysis is the ways that this proposal limits the mobility of francophones from outside Quebec. Montreal and Quebec both have a lot going for them as metropolitan areas in which to live, especially as younger Ontarians are being priced out of home ownership. One obvious path for many 18 year olds is to attend U de M or Laval and then remain in the province long-term. Creating such differential tuition fees with New Brunswick or Ontario universities to study in French limits this. For many anglophones, going to Laval and staying in Quebec would be a good option, but this is also precluded and the impacts on interprovincial mobility of younger francophones and bilingual Canadians is not good for a province going forward. There are also the specific implications for the communities on Highway 11, with large francophone populations and the nearest university being UQAT.

I can’t swear to this but I think the proposed increases will only apply to out-of-province Canadian students attending anglophone universities. If I’m wrong, I’m happy to be corrected. If I’m right, it’s even harder to swallow and more difficult to conclude that this is not at least a bit rooted in populism and some degree of animosity towards the anglophone community/ROC.

I’ve been legitimately shocked by just how many people are saying that the new, higher tuition for out-of-province students — reported to be about $17,000 — is still on par with (or even cheaper than) tuition in Ontario and other provinces. That’s very far from being the case!

Why it is not a good public policy to have a similar / comparable university tuition cost for Canadians out of province?

For example, only tuition cost for a year (2 terms) at Dalhousie University for a undergrad law program cost $17,981.00. The same program at Concordia is $8,991.90

Should public policies be evaluated from a horizontal and vertical equity lens?

If so, the current Québec policy on out of province tuition fee need to be re-evaluated.

Couple of things to note here. First, Dal has an actual law school (i.e., it grants actual law degrees), whereas Concordia, AFAIK, has only a ‘legal studies” program: not at all comparable. Second, university funding in Canada is a real dog’s breakfast that makes it hard to compare across provinces: some provinces have block grants (i.e., universities just get a chunk of funding based essentially on historical factors), while others have program funding (i.e., students in different programs are funded differently for a variety of reasons), and Quebec has traditionally had “activity-based” funding, whereby the governments funds each course registration on the basis (supposedly) of the cost of operating the program (in other words, without taking program demand or future graduate earnings into consideration—that’s how high fees for law programs are typically justified). As well, different provinces have different rules about “privatized” (i.e., non-subsidized) programs for which government provides no financial support to universities. Few people object to differential funding for out-of province students in principle, but the debate in Quebec is really about a policy that’s clearly designed to be punitive, whatever rationale the government may want to trot out to justify it.

Concordia does not have a law program, does it?

Except for law, MBA and medicine, the highest tuition fee from ROC is charged by UT, 11K per year. The other ROC universities charge 6-7K per year. ROC charged in Quebec was compared to 6-7K level, but now increased to a doubled 17K.

Nice piece. Where did you find the numbers on the number of OOP students in quebec vs ontario?