Good morning all. Today, the CD Howe Institute is releasing a paper I wrote on Performance-Based Financing (PBF) called Funding for Results in Higher Education. It’s a quick tour through the various ways that performance-based financing works around the world—in France, Germany, Scandinavia, as well as the United States—as well as some analysis of what we know of the PBF scheme that Ontario is theoretically implementing over the next couple of years. (NB: The Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities have, since this policy was announced, got a new Minister, Deputy Minister, and Chief of Staff, so who knows how well it will all play out). Please give the paper, available here, a read; I think it will help everyone get a better handle on what works and what doesn’t in performance-based funding. My thanks to CD Howe for releasing it.

I wanted to take this opportunity to talk about two “late-breaking” developments concerning the Ontario PBF file (aka stuff I did not find out about until after the final draft was in). The first has to do specifically with the proposal to measure students’ general skills and competencies as part of the PBF. I have described this before as being an idea which is interesting in theory, but uncertain in practice. In the UK, the Office for Students has been looking at different ways to try to measure “learning gain”—that is, to measure how much it is students learn over the course of their degrees. The work they did was impressive: a dozen different experiments at different institutions, which provided a wealth of perspective and knowledge, followed by a summary report. Would that any Canadian government with ideas about education were this thorough.

There is a lot of very interesting data in this report, but for Ontario’s purposes, the main finding of importance is on page 30. Based on analysis of attempts to measure learning gain using the CLA+ (which is a variant of the instrument likely to be used in Ontario), the report concluded that, “standardised tests […] have not proven to be robust and effective measures of learning gain due to challenges of student engagement, differential scores across socio-demographic characteristics, subject differences and use of data”. Also, with respect to the proposal to measure only generic skills rather than knowledge/competencies related to a specific discipline, the report says that, “contextual factors such as subject-level differences, institutional type and student characteristics differences impact the transferability of measures of learning gain. These differences should be considered when designing and selecting learning gain measures, and when analysing and presenting findings, and mediating effects need to be considered.”

In other words, measuring skills/learning gain, and attributing said gain to a program or institution, is still something of a moonshot. Not that it absolutely can’t be done, but the state of the art doesn’t yet seem to be up to the task—particularly not if funding is attached to the outcomes. Ontario might worthily keep up the effort to try to study and measure these things but putting it into the funding formula at this point seems unwise.

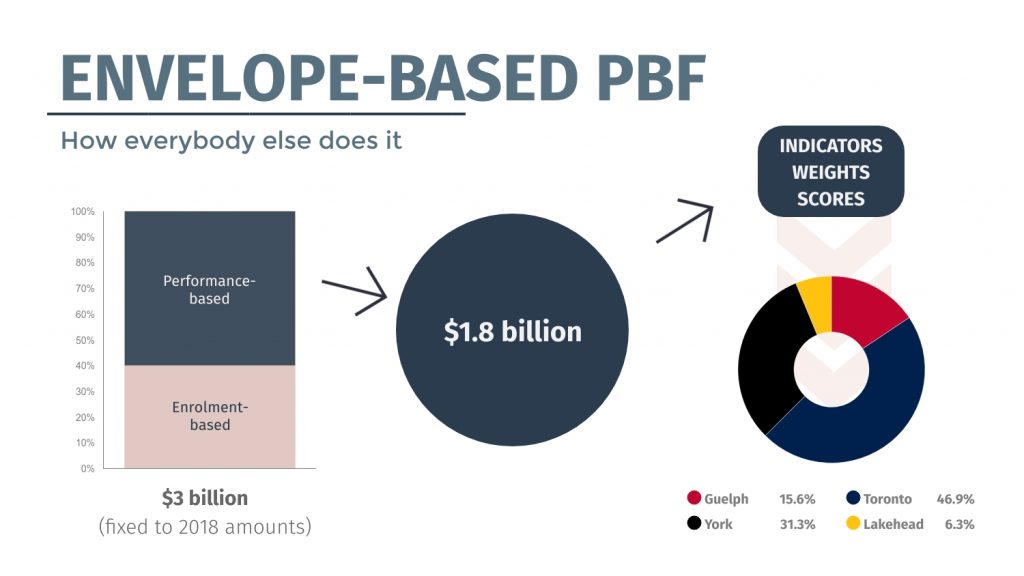

The second piece of news has to do with the design of the PBF system. In the spring I noted that most PBF systems worked on an “envelope” system. That is, the government carves out a portion of the grant to act as a performance “envelope”, and then based on institutional results, this envelope is divvied up amongst the institutions as shown below (which is a simplified model with hypothetical divisions).

(Will big institutions “win” in this scenario? Of course they will, just as they “win” now when an enrolment-based envelope gets divvied up based on weighted enrolment numbers. The competition is just based on outputs rather than inputs. This is entirely appropriate. Everyone breathe.)

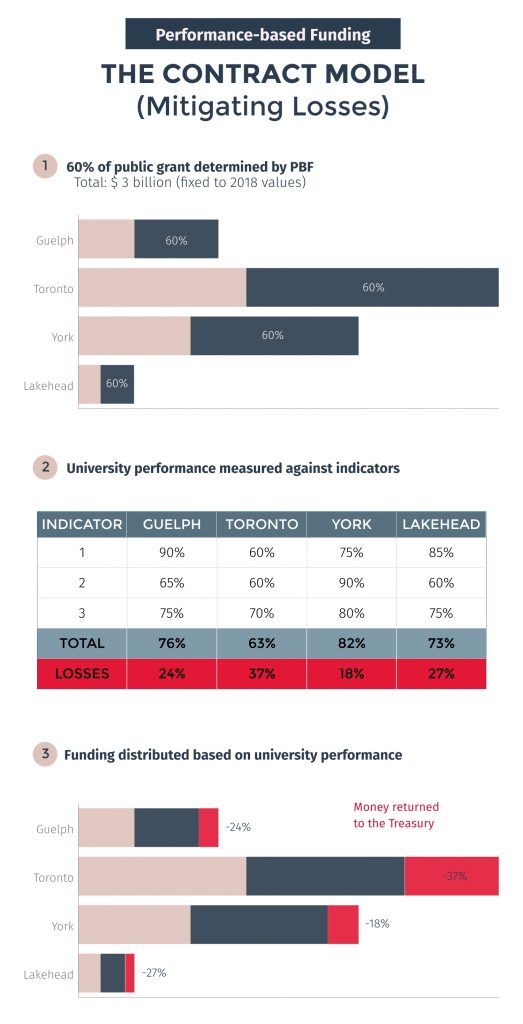

Now, as rumoured/feared in the spring, the Ministry appears to have been working all summer on a different kind of PBF, one which as far as I know has only ever been contemplated in North Macedonia. This is what I have dubbed a “contract” system of PBF, and it works a little differently. Basically, instead of one big envelope worth 60%, each individual institution is going to get 60% carved off its existing enrolment-weighted grant. It can win back this grant one indicator at a time. The institution and the government will negotiate the weight of each indicator – that is, how much of the 60% the institution can win back based on each indicator.

Now, you ask: how will the government know how much to give each institution based on each indicator? Well, as I have been given to understand (I apologize for the imprecision here, but since the government refuses to actually make policy in plain sight, one has to operate on leaks and rumours), the idea is that the government will set a target for each indicator. If you meet or exceed the target, you get 100% of the money available for that indicator. If you don’t, you get something less than 100% BUT—and this is the crucial bit—you can never get more than 100%. That is, institutions have to hit all ten targets to keep their current allocation. Doing extra-well in one does not make up for an undershot anywhere else. In other words, under present conditions where the total sectoral grant is frozen, there is no way for institutions to win under this system; there are only ways to lose less. To my knowledge, this would make Ontario’s PBF system the only one in the world that is all stick, no carrot.

The astute among you will have noted the obvious opportunity to game this system; namely, the setting of targets. Say your current graduation rate is 82%: what target will the government set for you on the graduation metric in order to get to keep your funding for that indicator? If it’s set very tightly to current numbers (say, 81%), there’s a very good chance that institutions will on occasion miss the target and hence lose money, and the money will go back to the Treasury. This option, in which PBF is really a set of disguised budget cuts, is what you might call “painful” PBF.

Alternatively, the targets could be set very loosely (say, 70% in the same circumstance), in which case almost everyone is going to hit their 100% target all the time. This is what I call “pointless” PBF. In theory, 60% of the money will be “based on” performance, but in the actual event, almost no money will really be at risk, and everyone will carry on with frozen funding levels based not on performance but on whatever their 2018/19 levels of enrolment-weighted funding were. And you can bet your bottom dollar this is what every institution will be lobbying for over the next few months.

It is not theoretically impossible to come up with versions of PBF which are neither painful nor pointless. But in the absence of any funding increases (which this government’s fiscal plan makes basically impossible before 2022), it is impossible if one insists on a contract system. The government should ditch this idea and move to an envelope system instead.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post