I haven’t taken a good look at faculty salary data in about three years, so it seems about time to catch up on what’s going on out there. Let’s jump right in.

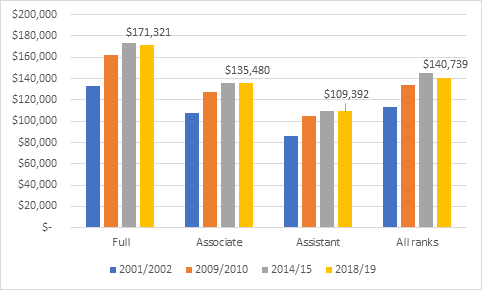

Here’s the big headline: for the first time in about two decades, average faculty salaries are declining in real terms, albeit from quite high levels. Among full professors and the faculty as a whole, the drop in inflation-adjusted salaries is about 3% since 2014-15; for associates and assistant professors the drop is less than 1%.

Figure 1: Average Professorial Salaries by Rank, Canada, Selected Years, 2001-02 to 2018-19

There appear to be a couple of things going on here. The first is that generally, faculty associations have accepted smaller pay increases over the past few years. The second is that the aging of the professoriate, particularly at the full professor level, seems to have slowed considerably or even stopped. So, the constant aging of the professoriate which started following the end of mandatory retirement has more or less ended because the age at which profs retire seems to have stabilized. This stabilization has occurred at an older age, but the mere fact that it has stabilized will reduce the tendency towards ever-increasing salaries. And third– and here’s the really counter-intuitive bit – the proportion of staff who are employed at a level below associate professor is actually increasing. That is to say, there is a fair bit of new hiring happening at lower ranks and this is bringing down average salaries.

This is frankly welcome news, because it suggests a more manageable path for institutional finances at a time when public funding is stagnating. It means that a more sustainable future is possible without having to rely on ever-increasing numbers of international students. It is, broadly, a Good Thing.

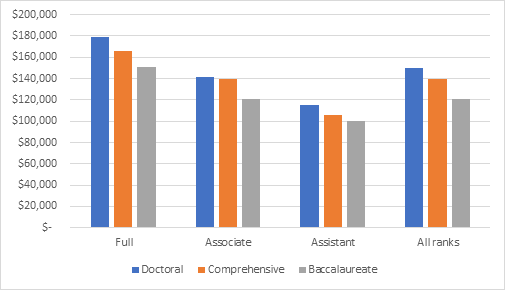

Of course, salaries are not equally distributed across institutions. For the following comparison I have divided institutions into three categories: “Doctoral” universities, Comprehensives, and Baccalaureate-level. I keep these definitions pretty close to the Maclean’s definitions, though I remove Sherbrooke from the top category, and include Waterloo, Guelph, Victoria and Simon Fraser. Figure 2 shows that professors at doctoral universities have about an 8% pay advantage over professors at comprehensive institutions and around 20% over those at baccalaureate institutions.

Figure 2: Average Professorial Salaries by Rank and Institution Type, Canada, 2018-19

(In fact, there’s a lot of variance within these categories, but that will have to wait for tomorrow).

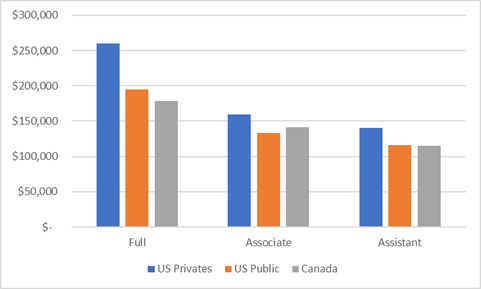

Now to the always-fun comparison with American universities. The American Association of University Professors publishes average salaries for Doctoral, Masters and Bachelor’s institutions, which I am going to take to be equivalent to the three categories I listed above (this is going to be a bit wonky – I suspect a few of the institutions I have listed as Baccalaureate in Canada would actually show up in the Master’s category in the US, but there’s no easy way to ensure exact equivalences, so we’ll let it go). I am converting US dollars to Canadian ones at purchasing power parity ($1.20 in 2018, according to Statscan), and for American doctoral institutions only I am giving a slight upward nudge in salary to account for salary derived from research grants and “summer salary” (details back here if you want to see how I am doing it.)

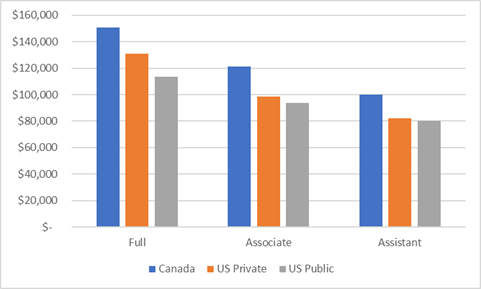

Figures 3, 4 and 5 show salary comparisons by type of institution and rank across US Publics, US Privates and Canada. Broadly speaking, they show two very different stories. The first is that at Doctoral institutions, which employ a much larger fraction of the faculty in Canada than in the US, Canadian professors trail at the highest levels, with the gap between Canadian universities and American privates as large as 44% at the full professor level (US doctoral university salary grids rise more steeply with rank than ours do). This isn’t necessarily a reason to feel sorry for anyone in Canada – I mean, come on, $178,000 is a pretty good wage, and on the whole our salaries line up with American public research universities – but it does show what Canadian institutions are up against when they compete for the very top research talent.

Figure 3: Average Salary by Rank, Doctoral Universities, Canada vs. US, 2018-19

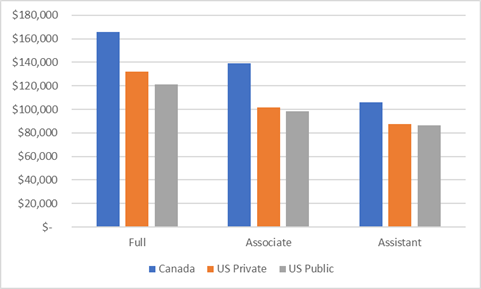

When it comes to Master’s and Baccalaureate institutions, we get a different picture. Here, Canadian institutions lead by a margin of anywhere from 25-40% against equivalent public US institutions, and from 15-35% over US privates. Partially, this is because US professors at these institutions tend not to be research intensive and therefore get paid over a 9-month period instead of a full year. But it’s also an effect of unionization, which in Canada serves to somewhat level salaries both within and across institutions.

Figure 4: Average Salary by Rank, Comprehensive/Master’s Universities, Canada vs. US, 2018-19

Figure 5: Average Salary by Rank, Baccalaureate Universities, Canada vs. US, 2018-19

So, to recap: Canadian professorial salaries are no longer increasing in real terms, and while salaries here are much better than counterpart American salaries at less research-intensive institutions, research-intensive universities are less competitive and lag badly in comparison to US privates.

Tomorrow, we’ll zoom down to the institutional level and also look at gender gaps in salaries. See you then.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

This strikes me as another example of how the Canadian university system is less stratified than the American system. And this has several advantages: it means that good researchers are more likely to actually teach, for instance, and that admissions doesn’t become so competitive as to incite corruption. It’s the reason that Canadians can get a pretty good degree anywhere, as you’ve noted before.

Canadian universities shouldn’t compete for talent so much as resist the whole star system altogether.

Most US salaries are for 9 months and in Canada are for 12 months. Is there an adjustment for the difference in the number of months paid? Many faculty in science and engineering in R1 universities find funding to add 3 months of summer salary making theirs a 12 month salary. This complicates the statistics.