By Alex Usher and Jonathan Williams

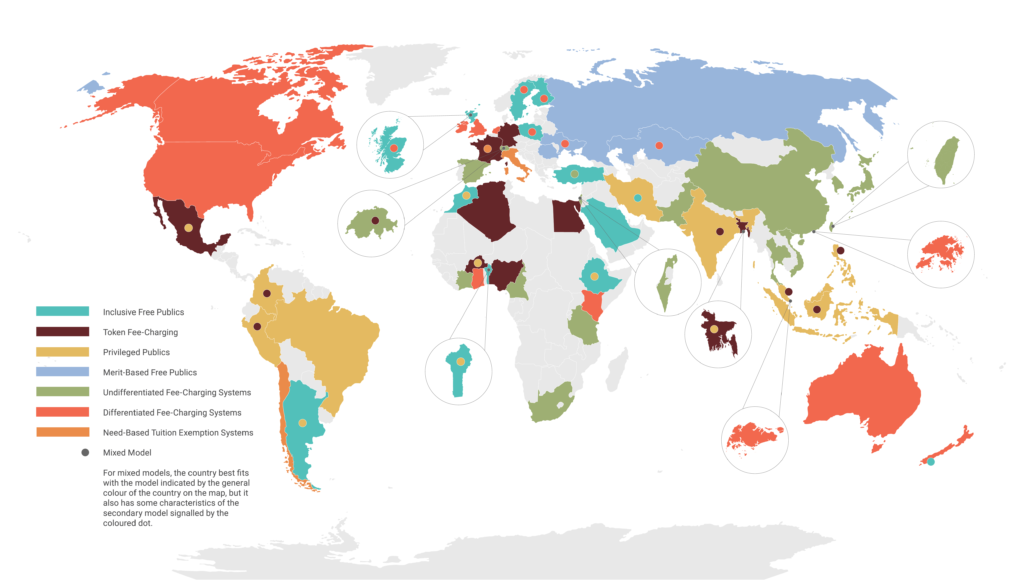

In the global discussion about tuition fees and cost-sharing, the most common – and the most simplistic – way to divide up countries is into countries which are “free tuition” and those which are not. But it’s not actually anywhere near that simple. When it comes to student fees, national systems vary along four axes. First, the gross enrolment/participation rate; second the share of students attending public higher education institutions (worldwide, roughly a third of all students attend private institutions); third, the share of students in public institutions who pay fees; and finally, the fee rates among those paying.

Now, technically, roughly 90% of all students globally pay some kind of fee for schooling; however, in many cases, these fees are quite nominal. Among countries where there is free or nominal tuition in public institutions there are four major types of policy regimes at work.

- Inclusive, free public systems: This is where the public sector educates most students without charging fees, and overall participation rates are high. Sweden is the most obvious example here (though Sweden charges high fees to students from outside the EU)

- Token fee-charging systems: The public sector educates most students while charging only modest fees. France is a pretty good example here.

- Privileged public systems: The public sector charges no or very low fees, but most students attend private HE providers. One sees a fair bit of this in low and middle-income countries; Brazil is probably the archetype.

- Merit-based free public systems: The public sector educates most students and exempts a substantial share of these students from paying fees based on merit adjudicated through university entrance examinations. This is the dominant fee model in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, most notably in Russia.

In other countries, ones where the charging of significant tuition fees is the norm, there are another three types of regimes:

- Undifferentiated fee-charging systems: Students attending the same study program and institution will generally pay the same fee rate (though student aid programs may in some cases offset costs for some students). China is largest country using this kind of system, though fees there can and do vary substantially from one program to another.

- Differentiated fee-charging systems: Here, students attending the same study program and institution may pay different rates based on characteristics such as citizenship. This mainly covers anglosphere countries with large numbers of international students who pay differential fees (also the United States where high out-of-state fees are widely used). In practice, this can look a lot like the merit-based free systems with the two tiers of payment; the difference here is that pretty much everyone is paying at least some fees.

- Need-based tuition exemption systems: Students may be exempt from paying study fees based on need or income. Italy and Chile come closest to this model.

The beautiful map below (I know, it’s a bit small but click on it and it will enlarge), created by the HESA Design Collective, shows how these different regimes are spread around the world. Not all systems correspond entirely to one of these seven descriptions – some have features of a second system, and on the map, those are indicated by dots coloured according corresponding to those used in the legend.

Cool, huh?

Want to read more on tuition fees around the world? HESA’s World Higher Education: Institutions, Students and Funding will be released on March 31. Read all about it.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

This classification considers 1 type of financial aid – fee exemptions – but excludes other types of financial aid such as loans and perhaps also grants. Starting with Australia, many countries have income contingent loan schemes which effectively turn into grants for former students with low incomes. While those loans – effectively grants are only around 25% of total loan amounts in Australia, I think they are around 50% in England (which the post Augar proposals seek to cut) and thus change substantially the nature of England’s fee regime.

I understand this complicates the typology, but is it informative to include 1 type of financial aid but not another?

When the full report comes out you’ll see how we handle this. There is a chapter on fees, and another on aid. Each has a map like this.