So, now that China has 30 million students and a half-dozen “world class universities”, where to next?

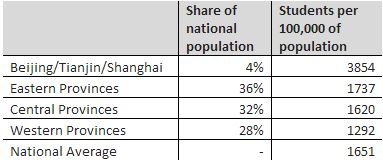

Well, the first thing to note is that the system hasn’t finished growing. While the major metropolitan areas of the north and centre have PSE attendance rates that approach those in Canada, outside of those very small areas, the average is less than half that. Even in fairly prosperous coastal provinces like Zhejiang and Guangdong, participation rates are less than half of what they are in the rich metropolitan zones. Now, some of the growth in participation rates will be taken care of via demography. China’s 20-24 age cohort will shrink in size by about a third between 2011 and 2016 thanks to the One Child Law (demographically, think of China as just a really big Cape Breton), so participation rates will rise significantly even if China does no more than stay steady in terms of enrolments. But it’s still a safe bet that in most of the country, we can expect more universities to open, and existing second-tier institutions will need to be expanded.

Participation rates by Region, 2008

So with demand for education set to rise, and the country still struggling to absorb all the graduates from the past few years, I suspect the bigger issue going forward for China is going to be quality. China’s worked out how to expand its system. What it hasn’t done quite yet is worked out how to spread excellence beyond its top research schools (the Chinese equivalent of the Ivy League is the C-9: Peking, Tsinghua, Fudan, Zhejiang, Nanjing, Harbin Tech, University of Science and Technology of China, and the Jiao Tongs at Shanghai and Xi’an).

And even at these schools, some of the excellence is only skin deep: they might be able to butt into world league tables based on publication counts, by doing things like requiring all graduate students at 985 universities to get two publications in Thomson ISI-indexed journals (seriously… can you imagine doing that here? The system would totally collapse), but those articles’ citation counts are much lower than at large western universities, indicating that the rest of the scientific world doesn’t think they’re up to much. But changing that means changing academic cultures – some of which have become sclerotic and corrupt (this stinging editorial in Science magazine [link is to an ungated copy] by two Chinese academics who had returned home from academic careers in the US, Shi Yigong and Rao Yi, is one of many pieces of evidence that could be cited here). As we know here in North America, there is very little that is harder than changing academic cultures. If China works out how to fix that problem, then there’s genuinely no reason it won’t lead the world at pretty much everything. But I have my doubts.

The outlook in China then is pretty simple – mostly continuations of recent trends, with a greater emphasis on quality and employability. And until they get that sorted out, there will continue to be opportunities for western institutions seeking to poach those who can’t get into 985 universities.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post