On Wednesday, someone took me to task in the comments section of the blog for part of my analysis on the financial situation of higher education, saying:

“The HE sector has hiked tuition up far faster than inflation citing “Increased teaching costs”. They have been unable or unwilling to provide proper costings for this.”

Is this true? Well, it depends how long a time-frame you choose to use. Let’s look at the data.

To look at “teaching costs”, we need to use data from the Statscan/Canadian Association of University Business Offices Financial Information of Universities and Colleges (FIUC) survey. FIUC divides salary costs into three categories – “academic ranks” (meaning permanent academic staff), “other instruction and research” (meaning mostly sessionals), and “other salaries and wages” (meaning non-academic staff). Unfortunately, it does not break out “benefits” costs in the same way – these are all lumped together in a single category. It also allows you to divide these up by “function” (admin, student services, libraries, etc.)

For this exercise, I will restrict the analysis to expenditures under “Instruction and non-sponsored research”, and include salaries for both permanent and sessional academics. Within this category, these two groups make up about 80% of all salaries, so I’m going to assign 80% of all benefit dollars as well (this is probably an undercount because academic staff tend to have better benefit packages). Together, I will call these “core teaching costs”. I will then going to divide total expenditures on these three areas by the number of “full-time equivalent students”, which, according to Statscan, = FT students + (PT students/3.5)

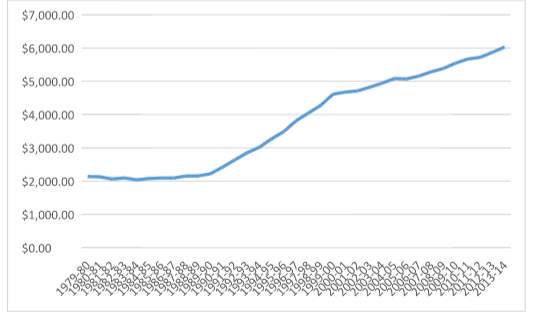

Here’s what that looks like, in $2016, back to 1979-1980.

Figure 1: Core teaching Costs per FTE Student, Canada, 1979-80 to 2013-14, in $2016

So: a major decline in per-student core instructional costs from 1979 to about 2003, of about 20%, followed by a decade of increases – mainly on the benefits side – which saw costs rebound by 17% to bring us up to our highest point since 1980. In other words, the story is pretty mediocre if you look at a really long view, but not bad if you take a lend of a decade or so.

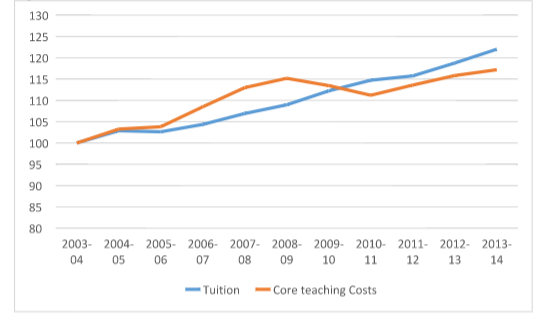

Now, to tuition, which is much simpler to track, using the standard Statscan tuition: average undergraduate fees across all programs.

Figure 2: Average Undergraduate Tuition, Canada, 1979-80 to 2013-14, in 2016

That’s a pretty simple story: flat in real dollars through the 80s’, sharp increases in the 1990s and more moderate ones since then (if one were to include subsidies like grants and tax credits, it would be close to flat since 2000, but let’s not complicate the analysis).

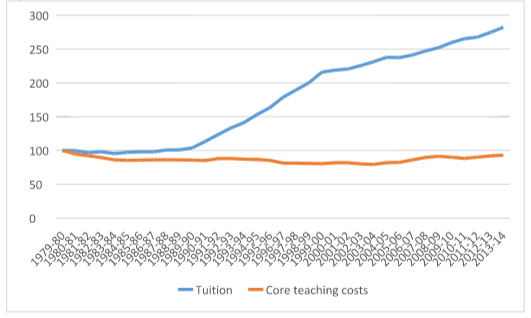

Now let’s compare what’s going on here over a 10 and a 35-year horizon. Figure 3 shoes that if you confine the analysis to the last decade or so, tuition and core instructional costs are rising at similar rates.

Figure 3. Tuition vs. Core Instructional Costs, Canada, 2003-4 to 2013-14, 2003-04 = 100

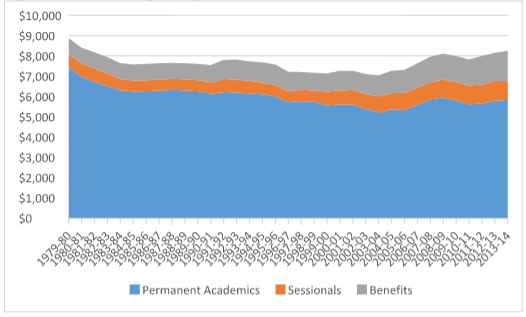

However, if you extend the analysis back to say 1979, you get a completely different picture.

Figure 4. Tuition vs. Core Instructional Costs, Canada, 1979-80 to 2013-14, 1979-80 = 100

Why the difference? Well, mostly because the 1990s were a time of disinvestment, so in part higher tuition fees were replacing government spending, but also because between 1990 and 2005 or so there were some fairly major changes to the way universities spend their money. A lot more money went into IT, student services, scholarships (and, yes, administration), meaning that core instructional costs shrunk as a percentage of total expenditures. So my comments-section interlocutor is certainly right over the long term, less so over the short term.

That said, there is a real question about whether or not those “core teaching costs” are really meaningful over time given the appearance that an increasing portion of staff time is devoted to research rather than teaching. But that’s a debate for another day.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

One other cost that doesn’t seem to get considered is overhead; keeping the lights on and classrooms heated/cooled costs a lot more these days. Things have changed radically since overhead projectors, blackboards, and chalk of 1979-80, and even in the past decade. Today’s classrooms are wired and wireless; and students of today expect modern conveniences and grumble when profs go back to the old blackboards. Students also expect courses to come with online access to notes, readings etc. (i.e. WebCT, Blackboard, Moodle, and other online course management software) and that costs money. All the gadgetry costs money. Then you need all the techs to keep the modern gadgetry going. I’m not saying overhead costs represent the largest chunk in the rise of the costs of teaching, just that it must be factored in.

Now, the debate over whether all that tech has improved student learning outcomes is a different discussion…..