After publishing yesterday’s piece, in which I updated a 5-year-old data analysis on spending on academic vs. non-academic salaries, I got a burst of unwarranted optimism and decided to try to do the same thing with another five year-old analysis on the same topic using institutional data – or at least institutional data from the dozen or so institutions who bother to publish this stuff. Sounds simple, right? I mean, if they published data before, they must publish it now, right? How tough could this be?

Last time out, I got reasonably long-period data sets on actual employee numbers – both academic staff and Administrative and Support (A&S) staff from twelve universities (UBC, SFU, Calgary, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, York, Toronto, Western, Waterloo, Carleton and MUN). Quebec institutions are a write-off, since none of them publish anything on staff numbers. Dal publishes nothing in this area, and UNB at the time had its numbers under lock and key. Queen’s does this irritating thing where they publish hard numbers on a “quick facts” page but don’t archive anything and use of the Wayback machine yields a spotty data set. But other than that, most of the big Ontario and Western institutions had decent data.

And I have some sad news, friends. If anything, Canadian universities are getting worse at publishing data about staff. UBC now puts its data behind a firewall, while the University of Saskatchewan – which used to have flat out the most detailed staff statistics in the country – has password-protected this data. So, to my friends at both institutions: you’re great, I love you, but the secrecy thing is juvenile, and you need to stop.

On the plus side, UNB has removed its passwords and now publishes all its data (yay!). And genuine love to all the folks at York and Carleton who run simply the best institutional data websites in the country. You are my peeps. Everyone should be like you.

Anyways, the upshot of all of this is that I can’t completely update the work of five years ago in the sense of adding five years to the existing data sets. What I can do, sort of, is show you what’s going in the most recent data. And so, in this exercise, I am just going to show the change since 2010 in both academic and non-academic staff (about half of all institutions can report data for 2019, most of the rest for 2017). It’s percentage points only, because different institutions have different ways of producing staff counts (headcounts? FTs? FTEs? It gets complicated) and different ways of showing coverage; in particular, for non-academic staff there seems to be quite a difference between those who include all staff or just those paid out of the operating grant. There’s also variation in how academic hospital staff are counted. So, I am not going to get into total numbers because I don’t think they are meaningful. But percentage increases are useful.

Some notes about the data:

- Take Western with a huge grain of salt since they only publish data on their A&S staff who work in faculties. As far as I can tell, they publish no campus-wide data that includes central admin. Also, a hundred demerits to Western’s institutional research shop for making people click on a dozen or so faculty links in order to aggregate data into something like a meaningful campus-wide number.

- I’ve manipulated the data gently at Calgary and McMaster to deal with the fact that data definitions seem to have changed halfway through. Details on request.

- The base year for UNB is 2011 rather than 2010.

Ok, enough preliminaries. After machete-ing our way through the jungle of institutional research datasets, what do we find?

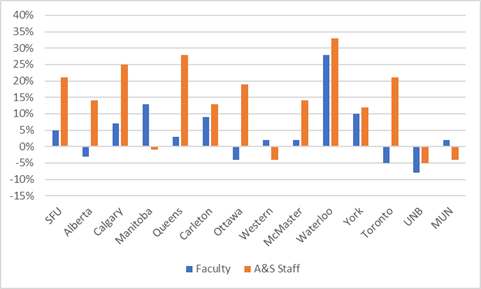

Figure 1: Percentage Growth in Academic vs. A&S Staff numbers, Self-Selected Institutions Who, Can You Imagine It, Actually Publish Staffing Data, 2010 to most recent year available

Ok, this is going to take some explaining. Across the 14 institutions where I was able to obtain data, the average increase in academic staff numbers is plus 4%. The average increase in A&S staff numbers is 13%. And at some institutions – notably, Queen’s, Toronto, Ottawa, SFU and Alberta, the gap in hiring is substantially higher than this. There was variation: at MUN, Western and especially Manitoba, growth in academics hired outpaced growth in A&S positions. But this was decidedly not the norm.

Again, I’ll just note that there are limits in how useful these measures are in comparison to one another because, at least as far as A&S staff are concerned, each institution is including or excluding different things, and that has a significant effect on the relative growth numbers. What you should focus on is that consistently, no matter what numbers you use, growth in A&S staff numbers are higher than for academic staff.

Now that sounds pretty damning: but remember what we learned yesterday, on a higher quality data set: across the country, aggregate pay for the two groups is actually growing at very similar rates. But how do we reconcile that data with what we see above? There are a few possibilities.

- This group is full of outliers, and institutions not in the survey have the reverse hiring pattern, and thus taken together the national picture might be closer to what we saw yesterday (I am skeptical).

- The national rates of pay we saw yesterday look very different at thee fourteen institutions than elsewhere, and so there is no discrepancy (this is a variant of the first argument, but a testable proposition, nonetheless. I might come back to this next week).

- The rates of pay in the two sectors are diverging; even while A&S hiring is increasing, average rates of pay are declining, mainly because new jobs tend to be at lower pay levels (this seems most likely to me)

Bottom line: nationally, spending on university administrators is no more out of control than spending on academic salaries. But at a number of nationally-significant universities, there does seem to be a substantial difference in hiring patterns between academic and non-academic staff. Understanding this would take some more involved institution-by-institution analysis than I’ve been able to put together tonight. (Sorry).

Another interesting blog tomorrow, since today is that blessed day when Statscan bothers to update post-secondary enrolment statistics and ever so briefly its data trails reality by only 28 months instead of 30 months, and our national statistical system trails Nigeria’s by only four months instead of sixteen. I hope you can stand the excitement.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post