Basically, Canadian higher education programs can be divided into two types. First, are programs that must be accredited, and where graduates’ ability to work in their field is tied to accreditation (e.g. Law, Medicine, Engineering). These programs start with desired outcomes, and work backwards to make sure that graduates have the skills required to meet professional certification. Second, there are the Arts and Sciences, which more closely resemble a free-for-all, in which curriculum is driven at least as much by faculty research interests as by any sense of ensuring students graduate with a coherent body of knowledge and skills.

(Yes, yes, there are in-between cases, like business, where accreditation occurs but is not tied to professional practice, and so isn’t quite as rigorous on the outcomes side. Leave these aside for the moment.)

It wasn’t always this way. Back before World War II, Arts and Science degrees had much more standardized curricula. They weren’t by any means designed according to 21st Century learning outcomes-lingo, but a lot of thought did go into what specific body of knowledge Arts students would master. It was only in the 1950s and 1960s that the smorgasbord approach to arts education became standard (a story which is entertainingly told by Louis Menand in his book, The Marketplace of Ideas).

But it doesn’t need to remain this way. There’s actually a lot that Arts can learn from some of the regulated professions, in particular from medicine where Canadian curriculum is considered one of the world’s best.

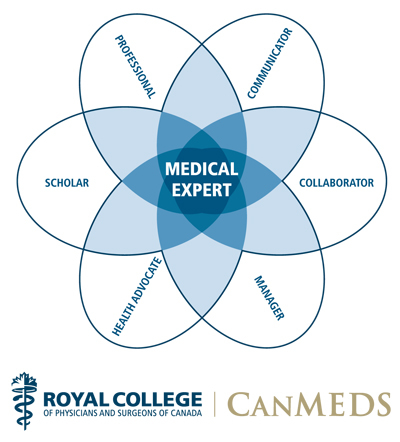

Take a look, if you will, at something called CanMEDS. It’s a curriculum framework that applies to the residency training of all the medical specialties under the auspices of the Royal College of Physicians. The College started by working out what kind of people they wanted doctors to be. What they decided was that, in addition to being a medical expert, it was important for doctors to play six other roles – that of: i) communicators, ii) collaborators, iii) professionals, iv) managers, v) health care advocates, and vi) scholars. All medical residency training since 2005 has incorporated not just training to those ends, but also frequent assessment activities as well. And it’s so well-regarded internationally that countries like the Netherlands (no slouches in professional education) have adopted it wholesale for their own medical training.

Now, there’s absolutely no reason one couldn’t structure an Arts curriculum the same way. The expected role graduates should play wouldn’t be the same, obviously (though keeping subject matter expert, communicator, and collaborator seem like no-brainers to me). Then you’d work to build-in activities and assessment for all of these intended roles/outcomes in every single course. And if you couldn’t do that (it would likely be difficult in larger classes), you’d find ways to create new mandatory modules that develop and assess more specific competencies.

There’s no really good reason – other than inertia and intransigence – why it couldn’t work. And the upside would be enormous. Students who graduated from such a program would have actual tangible evidence of skills and competencies, as opposed to all the “we’re-not-sure-how-but-boy-

Who’s first?

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Alex, I think you are right to point to the history of the liberal arts degree to create some context for “okay now what.” Many people don’t acknowledge that the “old” liberal arts model was also very elitist — it was much easier to have a more standardized curricula given 1) the homogeneity of the student population (white guys with money) and the low-stakes of the whole thing (liberal arts as “finishing school” rather than for vocation).

Points AGAINST greater standardization: if we are indeed serving and representing a much more diverse population, a more diverse curricular offering would seem appropriate. It’s also important for the advancement and evolution of scholarship in the humanities. And hopefully there’s no need to defend academic freedom and the value of good, critical, independent thinking and communication?

Points FOR greater standardization: much as many of us educators cling to the ideal of education “for it’s own sake,” vocational aims, for better or for worse, seem to rule most students’ interests. A degree that doesn’t “pay off” in the labour market seems a luxury few students and their families can afford. Further, the “smorgasbord” you mention is probably confusing for students and employers alike — driven more by competition and “niche marketing” of courses, programs and institutions than by what’s best for students.

It’s a complex question. Fundamentally, it seems to me we need to consider what a liberal arts degree is all about. The private “returns on investment” (I cringe to use the term) seem tenuous for general arts and sciences degrees. But there are important public benefits. And if they are indeed deemed public benefits, we gotta figure out how to pay for them, and who ought to learn what for what reasons. I accept there are certain vocational realities accompanying contemporary post-secondary education, but there are other important values and outcomes that can’t be sacrificed just to get the degrees articulating with the labour market.

Great post.

I would agree, by the way. I don;t think the outcomes you have to pick need necessarily be ones that are LM-friendly. My point is simply “pick some outcomes and design your curricula to focus on them”.

I can see a sort of Scylla and Charybdis problem here. If you make the requirement old-fashioned — say, like a great books curriculum — then half the faculty will shrink from it as Eurocentric. On the other hand, if you make the requirement abstract (say, with “breadth goals”, “communication ability-forming” or whatever) then it’s probably administration-driven and may end up meaning nothing at all.

Thanks for your interest in our CanMEDS framework. We designed as a way to reconsider medical education. It seems to have resonated with others, as it is now used in more than 26 countries and for 14 professions. This is the first time I have heard it used as a way of considering a liberal arts education.