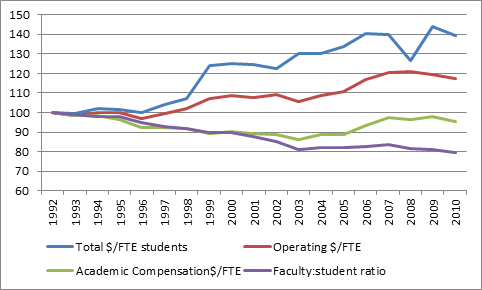

We’ve covered a lot of ground in the last few days. Back on Tuesday, we asked the question why faculty-student ratios could fall by 20% over two decades when per-student income had jumped by 40% over the same period. The best way to sum up the answer is with the following graph:

Changes in Total and Operating Income per Student, Academic Salary Mass, and Student-Teacher Ratios, Indexed to 1992

The top line is total income per FTE student. That rose 40% between 1992 and 2010, most of it in a few glorious years in the late 1990s. The next line is operating income per student, which only rose 20% per student over the same period. That’s still good, of course, but it does mean that other parts of the university were receiving money at a faster rate than the operating budget was.

Now let’s look at academic compensation. Despite an increase in the operating budget, total academic compensation (i.e., salaries + benefits) fell. All of that fall happened prior to about 2002 – since then, the two have moved more or less in tandem. What that means is that a lot of money within operating budgets was being moved into other areas. As we saw on Wednesday and Thursday, the big “culprits” were scholarships, utilities, and, to a lesser extent, central administration.

Finally, there’s the faculty:student ratio, which fell more or less in lockstep with academic salary mass until 2001. After that, individual faculty salaries began to rise. Thus, even as total academic salaries stabilized, that amount bought ever fewer professors, because their real salaries were rising.

And that’s basically the story. Billions of dollars went into the academy in the last twenty years, coming from students, government, and other sources. But a disproportionate amount of that money went into non-operating areas (such as research). And a disproportionate amount of operating money went into areas other than academic salaries. And average faculty wages rose substantially in real terms.

That, ladies and gentlemen, is how faculty:student ratios can fall by 20% while income per student rises 40%. And it’s worth underlining here: virtually all of this has to do with changing priorities within the academy, not changes in government policy. It was universities who urged the new focus on research. It was universities which made the decision to favour other spending categories over academic salaries. It was the academic community as a whole which decided to pay more money to fewer professors, rather than keep salaries stable and hire more staff. No one made the academy do this. It’s a self-inflicted wound.

We have met the enemy, and he is us.

6 Responses

Hi Alex

I think you are right that the universities made choices that led to this situation. But you are letting the governments off the hook. Certainly in Ontario (and I believe elsewhere) the government has put a big push on graduate education which requires expansion of the research activities and also requires more faculty per student. This, of course, is unrelated to administrative bloat which is a different issue.

I thought this was an excellent thought-provoking series.I am still not clear about the distorting impact of research dollars, a huge shift from the 90s onwards for many universities. If you put these dollars in with general government support, I would have to say that the government was pushing an agenda, not just the universities, in which case the “enemy” is a bit more complicated than just “us”, though we happily received the gift … and asked for more. But this series really was good. Thank you.

I would question to a ggreat extent your assertion that we asked for the greater focus on research, or at least that the impetus for that didn’t come from government. Probably the major shift in the way funding flows from government that occurred in this period was the cut back to transfers from the feds to the provinces in the 90’s and the backfilling with additional money for students and for research, all part of a federal desire to funnel money more directly to universities and get some credit for it. My reading at least from where I am is that the change in where money was available from prompted a change in administration’s focus and faculty reacted by saying you want more research? Cut our teaching and give us more credit for doing the research.

1) The argument on offer misapprehends the nature of the university labour pool. The issue here is that investment in scholarships for graduate students IS an investment into the labour pool of FT professorial staff. In most disciplines, graduate students are cheap, well-trained labour that make contributions to the research ecology that are not in proportion to their level of compensation. This issue has been high-lighted by a number of research organizations in the US, as I know you are aware.

2) Shouldn’t the drop in salary mass be expected? The percentage rate of compensation increase (while being so significant as to remain undisclosed in some quarters, as you point out) is outstripped by the percentage increase in overall revenues. Of course, salary mass is going to decline! But, the issue is exacerbated when more students are taught by contract lecturers rather than well-compensated profs since every contract lecturer erodes the professorial salary mass. For that matter, the ratio between PROFS and students may have shifted as dramatically as described, but the ration between INSTRUCTORS and students probably did not.

3) The posts prevaricate on the matter of administrative salaries. At times the post wants to diminish the “bogey” of administrative salaries, while at others the post wants to acknowledge that administrative salaries have increased substantially but don’t tell the full story. Administrative salaries at universities have increased enormously by the very metrics adopted in these posts. The metrics don’t tell the full story since reported compensation often excludes benefits like housing, car allowances, etc. A typical car allowance could probably get two or three contract lecturers into a classroom. How about a simple Management Expense Ratio for universities?

My apologies. I should have added that the argument and analysis is much appreciated and very interesting. Please excuse my terseness.