As we saw yesterday, while student debt at graduation has been increasing, falling interest rates have meant that monthly student debt payments have made up a smaller share of a graduate’s income in recent years.

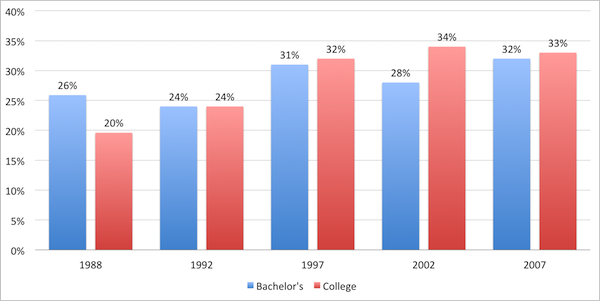

Of course means and medians only tell part of the story. While it may be true that the average borrower was better off in 2007 than in 2002 despite graduating with more debt, the same can’t be said for every borrower. As Figure 1 points out, the proportion of graduates reporting difficulty repaying their loans has hovered around 30% since 1997. It’s worth noting that the federal government expanded interest relief programs in the 1998 budget as part of a series of measures to tackle student debt. Since debt burdens have been declining in recent years, it’s unlikely the situation has worsened.

Figure 1: Percentage of Graduates Reporting Difficulties in Repayment Two Years after Graduating by Type of Degree, 1988 to 2007

Source: Statistics Canada’s National Graduates Survey

A ten-year retrospective on the graduating class of Canada Student Loan borrowers from 1995 offers two important insights. First, graduates who encounter challenges repaying their loans tend to do so soon after finishing school; 90% of defaults occurred within three years of graduation. Second, default (i.e., when students miss three payments or more) tracks graduate income, not indebtedness. While the debt load of students who defaulted was similar to that of students who did not, their income was much lower.

So where should student aid policymakers address their attention? As we’ve seen, rising debt levels can be more than offset by relatively low interest rates. But if interest rates rise, especially quickly, graduates may find themselves in trouble. Enter programs like the federal Repayment Assistance Program, which sets payments on the basis of income (not outstanding debt), capped at 20% of the individual’s family income, and discharges debt after 15 years (10 for those with permanent disabilities).

Unfortunately, borrowers must apply for RAP, meaning they must be aware of it. A 2006 paper looking at the CSLP’s interest relief program found that only 45% of eligible beneficiaries of interest relief took advantage of the program. In particular, borrowers on social assistance and with large families (i.e., those unlikely to have family members who can pay their bills) were relatively unlikely to apply for support.

As my colleagues have noted, the current student aid system works well because interest rates are low. A hike in rates, though perhaps not imminent, could raise the debt burden and cause government expenditure to balloon, upsetting the careful balance that currently exists.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

Is that the % of those graduating reporting difficulty, or the % of those graduating with debt reporting difficulty. As I suggested earlier, I think one thing you haven’t addressed is the proportion of students who access loans.

Jim,

It’s the percentage of borrowers who had government debt remaining after two years reporting difficulty (so those who had completely repaid their loans before they were surveyed are excluded from the denominator). As you can see on page 190 here (http://qspace.library.queensu.ca/bitstream/1974/5780/1/POKVol4_EN.pdf), the proportion of graduates with debt was in the mid-forties in the 1990s and has been in the mid-fifties since 2000.

The Canlearn website has the following definition of default:

Your Canada Student Loan is considered to be in default when you are behind on your payments for nine or more months and collection activities are required. Defaulting on your loan can disqualify you from receiving future student financial assistance or from applying for repayment assistance under the Repayment Assistance Plan.

You say a loan is in default at 3 months but my understanding is that loan would be delinquent but not in default because it is still held by the National Student Loans Service Centre. I didn’t know that delinquent loans were reported to the credit bureau so thanks for that information. Can you find out how many delinquent student loans are reported to the credit bureau annually and if there are any trends?

In reference to the StatsCan paper described above (the ten-year retrospective on student loans), the term default applies to a loan that has been in arreas for three months or longer. It’s worth noting that default is temporary – many borrowers who experience default go on to repay their entire loan.

I suspect getting information on the number of delinquent student loans would be rather difficult, especially if you wanted data over time.