All models are wrong, but some models are useful. This phrase, usually attributed to the statistician George Box, is especially apt when it comes to labour market forecasts. There is an obsession among policymakers about “getting better data” and “getting good labour market projections,” which can in turn (to some extent) drive planning for skills training and post-secondary education. And it is definitely a phrase that comes to mind when describing the new, bold labour market projection system described in a new paper entitled Ahead By A Decade: Employment in 2030, and published last week by the Brookfield Institute.

This new paper is – for reasons I’ll describe below – suboptimal in some ways. But it is, at the same time, hugely welcome because it takes some bold new methodological stances and stands in opposition to what (IMHO) is the increasingly stale methodology preferred by the Canadian government. So even though it is methodologically a bit off, the specific ways in which it is off improve our overall view of labour market futures.

To understand this better, we need to take a look at how the “Canadian Occupational Projection System” (COPS), the country’s dominant labour market projection system, actually works. Basically, this system makes labour market projections based on demographics and macro-economics. This approach asks “where is the economy as a whole is going and how will that affect the distribution of jobs”, and then adds in a layer of “what’s the demographic profile of specific occupations” in order to generate projections of the number of people entering and exiting each occupation. From there, you get profiles of jobs likely to expand and contract. This is what COPS does in a nutshell.

This approach kind of works and kind of doesn’t. In a country like Canada, a lot depends on the price of natural resources: project that wrongly and the whole thing is off. And the further in advance you are trying to project the labour market (the industry standard seems to be a decade), the harder it is to get these predictions right. The COPS data from the early 2010s are a mess for precisely this reason. This methodology also has a hard time dealing with public sector employment, because the issue of supply and demand for services is mixed in with a whole set of confounds since government is a monopsonist employer and its spending decisions don’t line up neatly with concepts like supply and demand (e.g. a few years ago when its projections suggested that the profession of “university professor” would be in hot demand because of retirements…oh how we laughed!) (Editor’s note: quietly sobs).

There’s one other big weakness to the COPS approach, which is that it is essentially blind to disruptive change. So, in the US, employment in the videotape and disc rental business dropped by 90% between 2007 and 2016, basically because of Netflix. That kind of technologically-driven change is almost impossible to predict using COPS-like models.

Given all those weaknesses, two cheers for Brookfield trying something new. Primarily, the problem that Brookfield is trying to solve is that last one: working out what kinds of disruptive change might affect the labour market over the next decade. There were basically three inputs to their model:

- Working on their own, in full futurist mode, Brookfield came up with 31 Trends for the Future (outlined in this document from about a year ago).

- Using some pretty cool methodology, they decomposed the skill requirements of 485 major occupations, which allowed them to – among other things – look at skills overlaps between occupations.

- In a series of discussions with labour market experts across the country, they presented the results from i) above, and then asked them what they about the prospects for 45 specific occupations – were the number of jobs in each of these areas going to increase, decrease or what, exactly?

This is where it all starts to get a bit…speculative. The reason Brookfield only asked about 45 specific occupations is because they correctly thought it would be impossible to ask about all 485. So instead, the selected 45 occupations were chosen because of the spread of skills they occupied. In effect, the strategy here was to deduce what experts thought of 485 occupations from their views about 45 by using various statistical techniques called “random forest classifiers”, “probability estimators”, and “sequential forward floating selection”. And then there is a bit of a demographic overlay, as in COPS, to add a dimension of retirements and new hires.

I think the best way to describe this approach is that it is creative: it’s not nonsense, but it is highly susceptible to garbage in-garbage out. Basically, what this model does is to work out which skills experts think will be in demand and work up from that to figure out what jobs will be in demand. There is absolutely no attempt here to work out what the actual macroeconomics of 2030 will look like. So, its accuracy basically depends on how smart you think their expert panel is, and how good their algorithm is at translating expert opinions on a very few occupations to a much larger range of applications.

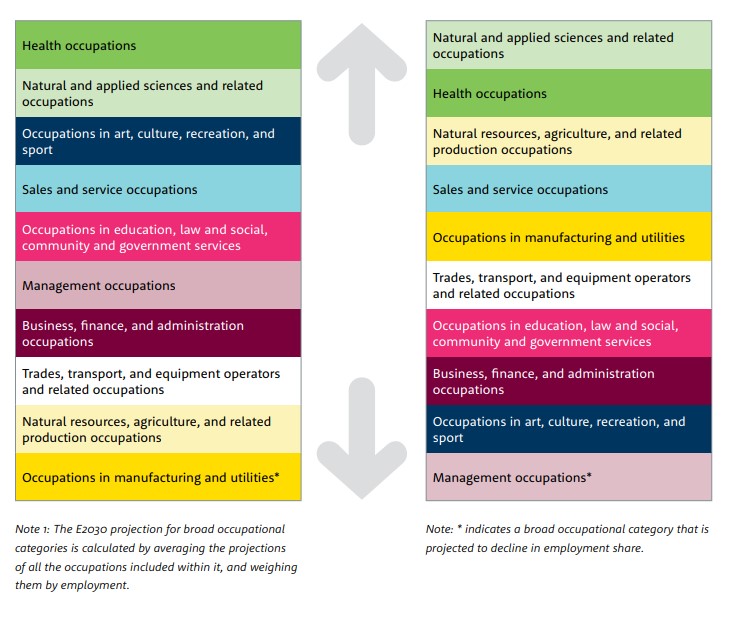

Not surprisingly, the Brookfield projections look somewhat different than the COPS projections. Here’s the helpful summary Brookfield provides (the left is Brookfield, the right is COPS, see pg. 36).

Basically, the Brookfield projection is a whole lot more sympathetic to the view that new jobs are going to require university-level education than the COPS view is. But is this real macroeconomics or is it just the predilections of a relatively small (128 people) group of labour market experts?

The thing to understand here is that COPS and Brookfield are using fundamentally different and, I would argue, equally unreliable methodologies. But – and this is the good thing – they are symmetrically unreliable. That is to say that what Brookfield has done is to complement COPS – be strong in areas in which COPS is weak and – IMHO – be weak in areas which COPS is strong. Ultimately, the truth likely lies somewhere between the two projections.

To be clear, that’s not a knock on Brookfield by any means. They have, at relatively low cost (compared to COPS) put together a good alternate take on the future of work and given us an alternate take on the labour market of 2030, which enriches the debate. When I say they are probably half-right, I do not mean this backhandedly in the least. This is a great alternate lens on the future. And by giving us a second lens, Brookfield has (IMHO) improved our foresight ability enormously.

So, you know, kudos. Even if you should take the end result with a grain of salt.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post