One of the things that many people misunderstand about higher education is the way the economics of classrooms actually work; in particular about the relationship between enrolments, teaching complements, teaching loads, and class sizes. Today and tomorrow, I want to tease these out a bit.

For this post, let’s take a faculty with 100 professors, which admits 500 students per year and has 10% attrition per year, which translates to 1720 students total. That means it has a student-professor ratio of 17.2 to 1. Let us further assume each student takes ten courses per year (yes, yes, I know—it’s just a model). That means 17,200 student credit-hours in total, which means each professor on average must teach 172 student credit hours every year.

Even in this kind of simple situation, faculties (or departments, or institutions) have enormous flexibility with respect to what kind of class sizes can be offered.

The first and most important variable in this equation is how to define teaching loads. Without changing the numbers of professors or students, you can vary class sizes significantly by altering teaching loads. If course loads were 3/2 (meaning three in the first semester and two in the second) and each prof taught five classes a year, average class size would be a little over 34. If, on the other hand, you have a more research-intensive institution and 2/1 or three classes per year is the standard, then average class size will be over 57.

(If you’ve ever wondered about the basic antagonism between research-intensity and the undergraduate experience, that last paragraph is it in a nutshell. More teaching-intensive institutions can produce classes which are 40% smaller for exactly the same cost—or even less, if you assume research faculty command higher salaries).

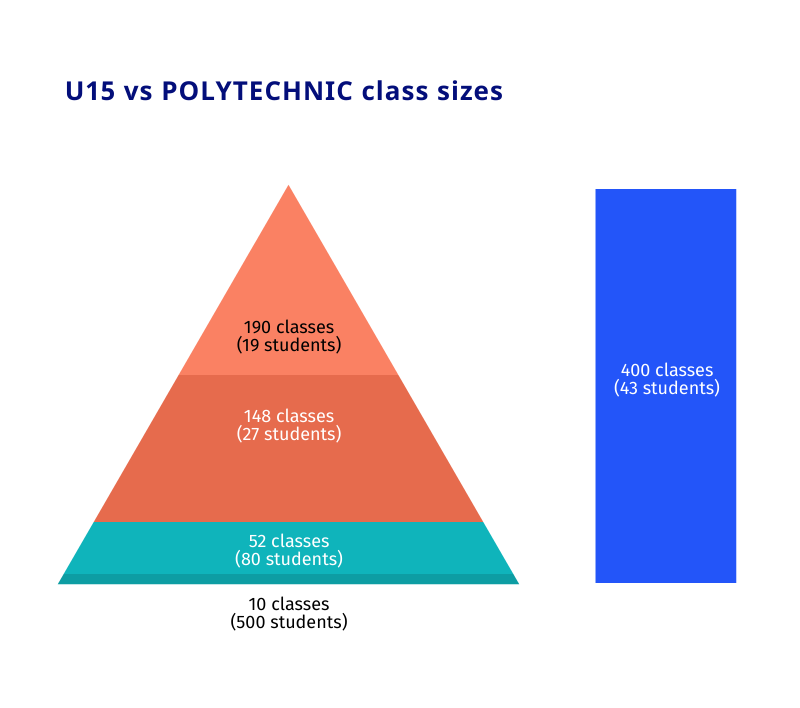

For the moment though, let’s assume a faculty half-way between those two: a four-class per year teaching average and therefore an average class size of 43. But averages are not destiny: faculties (again, departments/institutions/whatever) still have substantial control over class sizes even with a largely exogenous class average. To see what I mean, let’s look at two different class size management strategies.

The first is what I call the “Polytechnic” model because it’s closest to how polytechnics think about pedagogy and class size in their degree programs. Precisely because these programs cover somewhat niche subjects, a high proportion of classes are mandatory and so classes often move forward on what you might call a “cohort” model—that is, all the students in lockstep. So, if they have an average class size of 43, it’s a reasonable bet that 43 (or something close to it) will also be the median and the mode. Every class is a manageable 43.

The second is what I call the U15 Arts/Science model. Here, the focus is on a) allowing professors to teach a really wide variety of courses and b) making sure upper-year students at least get some very small classrooms. This is, in fact, more successful in delivering small classrooms than the cohort model: it is not actually all that hard to arrange class schedules and course loads so that half of all classes have fewer than 20 students. The only thing you have to do is accept a few classes of 500 or more.

Here’s the math: in a system where a faculty has to offer 400 classes (100 profs, 4 classes per term) and cover 17,200 student credit hours, it’s quite possible for a faculty to offer, for instance:

- 190 classes of 19 students

- 148 classes of 27 students

- 52 classes of 80 students, and

- 10 classes of 500 students

All for more or less the same cost as offering 400 classes of 43 students each (give or take the cost of a few extra TAs for those ten big classes). And depending on how these courses are designed and scheduled, that might in theory be better for students. Basically, it’s a balancing act between whether the engagement benefits of the many small classes outweigh the negative implications of the few very large classes.

In practice, of course, the U15 approach has some very big negatives: namely, because those big classes tend to be concentrated during students’ first year, before they are really comfortable with their new educational environment, they are almost certain to contribute to disengagement and drop-out when those issues are at their peak salience. But that’s not inherent to this kind of approach: there’s nothing saying these large, mondo-courses couldn’t be spread across all four years. It’s just a matter of designing a curriculum in a way that allows this to occur (in turn, this means that curricula have to be coherent, planned, unified things, not just a bunch of baskets of credits, but that’s another issue).

There are, of course, some limits to this kind of strategy: the main one being the actual sizes of available classrooms. I know some community colleges would dearly love to increase the sizes of some classes in order to preserve small classes in other areas. The problem? Architecture. You can’t have 500-person classes if you don’t have any 500-person classrooms.

Anyways, the point of all this is that small classes are always possible, even on relatively tight budgets. It’s largely a question of workloads, architecture, and a willingness to structure curricula appropriately. The more interesting question, perhaps, is: what are small classes worth? And when does the price of keeping them become too high? More on that tomorrow.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

This kind of thinking is sorely needed. I was hoping to see a major paradigm shift in college teaching coming out of the lessons learned from teaching during the pandemic, but alas, it looks like things will pretty much snap back to “normal” (including the normal dysfunctions), like a stretched rubber band that is suddenly released.