This is part II of a blog on new enrolment data. I’ll be focussing on the universities data today because the change there is more dynamic. (I know, I know, college peeps: I don’t pay enough attention to you. I’ll try to make this up to you next week).

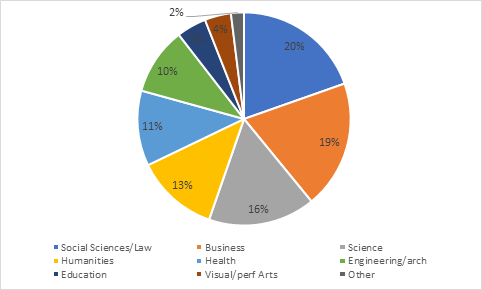

So let’s look at the division of undergraduate enrolment for a second. Figure 1 shows the split between fields of science. The Big Six are Social Science & Law (20%), Business/Commerce/Administration (19%), Science – here meaning a combination of physical sciences, life sciences, math/computer sciences and agriculture (16%), Humanities (13%), Health (11%) and Engineering (10%). Together these six fields make up almost 90% of total enrolment.

Figure 1: Shares of Total University Undergraduate Enrolment by Field, 2015-2016

That probably doesn’t sound too surprising on the face of it. But if you look at it from a longer-term perspective the change is stunning. As recently as 2001, humanities enrolments were the same size as social sciences and were roughly the same as health and engineering enrolments combined. Some of this change has been a very long process, but it has accelerated enormously since the financial crisis, as shown below in figure 2.

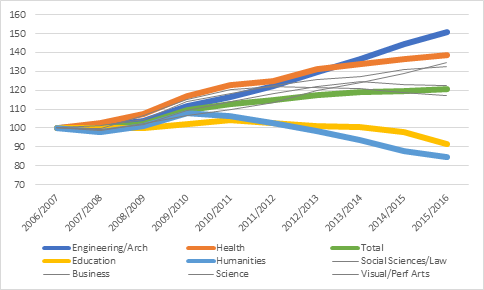

Figure 2: Change in Undergraduate Enrolments by Field, Canada, 2006-07 to 2015-2016 (2006-07 = 100)

In the period leading up to the recession, all undergraduate fields of study were growing. Not quite at the same rate, obviously, but the arrow was heading in the same direction for everyone. Then, after 2009, enrolments began diverging wildly. For demographic reasons, overall growth rates started to flatten out around 2009 and demographics are also behind the fall in education faculty enrolments (school boards are hiring fewer teachers as student numbers flatten or fall). Still, overall undergraduate enrolments continued to grow, albeit more slowly: by 10% between 2009/10 and 2015/16.

But what happens after 2009/10 is just a massive dispersion in growth rates, which, as far as I can tell, is likely unprecedented in Canadian history. Most fields of study grew by an amount equal to or slightly greater than the overall average. Meanwhile, Health fields grew by 18%, and Engineering by 35%. The rest of the sciences grew a little bit less quickly overall, but the math/computer science portion grew by a mindboggling 64%.

The humanities? Down 21.4%.

Now, this kind of thing is bound to cause friction. In some fields, people are going to be overworked; others will find their workloads lessening. But professors are specialized workers – you can’t just move them out of one field and into another. You can’t even get them to retire so you can hire a someone new in another area: they just hang on and on and on. You just have to make do the best you can.

But what one could do – at least in theory – is to start to cut back the number of PhD students you take in. Because in humanities – more so than in other fields – a doctorate really is supposed to lead to a teaching position. Of course, it doesn’t in practice for most people, and one learns some useful skills along the way – but that’s really what it’s for. So you’d think that with sliding undergraduate enrolments and hence reduced future job opportunities, humanities might be cutting back a bit on doctoral enrolments, right?

Wrong.

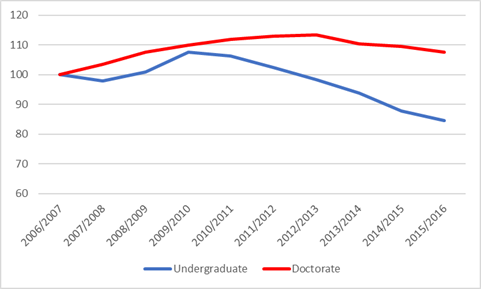

Figure 3: Change in Humanities Enrolments by Level, Canada, 2006-07 to 2015-2016 (2006-07 = 100)

Now, you wouldn’t expect doctoral enrolments to fall quite as quickly as undergraduate ones. They take longer to finish, for one thing, so it takes longer for a drop in new enrolments to be reflected in total enrolments. But you’d still expect them to track a little better than this. Figure 3 effectively implies a big and widening gap between PhD completions and future academic job prospects. A genuine question thus arises: are humanities faculties telling their doctoral students about this widening gap? And if not, why not?

Enrolment shifts have profound consequences to universities and we are currently undergoing one of the biggest – if not the biggest – in history. It is somewhat surprising that we are not having more open conversations about the effects.

Tweet this post

Tweet this post

In light of the enrolment trends identified in the above posting, readers may be interested in this piece on the value of the humanities and social sciences.

https://theconversation.com/is-there-too-much-emphasis-on-stem-fields-at-universities-86526

Paul Axelrod

Not surprising. For twenty years universities have told anyone who would listen that a bachelors degree leads to higher employment and higher wages. (And we were very quiet about whether this was really a cause and effect). So governments responded by funding programs that solve labour market shortages (e.g. “Double the Opportunities” in BC in early 2000’s). At the same time students (and their parents) chose programs where there is a clear pathway to a high-paying, secure profession (and that ain’t critical theory or cultural studies!).

In a previous blog Alex noted the high number of professors aged 65+. We can partly solve the imbalance of student numbers and faculty numbers through one-time incentives for the ageing professoriate in the humanities to retire, and then redirect the salary budget. SFU did this with some success after the financial crisis in 2008.

Precisely, Jon. We’ve been saying for some time that the goal of a university education is a job. Variations are other separable goals, like economic growth or social justice.

The logical response is to just concentrate on whatever will get a job, enhance the economy, produce justice, or whatever, and eliminate everything will contributes to a real (i.e., not applied) education, an education as an end in itself, a truly liberal set of studies, as a distracting speed-bump.

We should recognise that humanities programs continue to produce far too many PhDs because the humanities and their practitioners are judged by universities and funding bodies on criteria invented for the sciences. It might make sense to produce more highly-skilled individuals by way of further PhD programs in sciences, or to judge scientists by the extent of their funding, but it makes very little sense to apply similar criteria to humanities.

The trends are broadly similar in New Zealand and about the same scale.

From 2008-2015, domestic degree enrolments overall grew 8%. The mix changed in favour of engineering (+43%), health (+38%) and ICT (35%). The % in sciences and commerce stayed fairly steady. Society & culture enrolments fell by 4.5% (but “humanities” fields did a bit better with enrolment change near 0%). Creative arts enrolments also fell 4.5%.

Interestingly, the mix of fields of study has changed more in NZ with limited growth and capped funding system than in Australia which has had rapid growth in enrolments and demand-driven funding. This suggests the mix of student demand is heavily influenced by what universities choose to supply…

Data – http://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/statistics/tertiary-education/participation http://highereducationstatistics.education.gov.au/