About two months ago, we did a series on bibliometrics (if you missed it the first time out, you can catch up here), and promised we’d be back shortly with some new results. Well, we’ll those results will be released Wednesday, and we think they’re so interesting that we’ll be spending all week telling you about them.

For bibliometrics to be really useful, they need to (a) be able to capture information about both productivity and impact, (b) be easy to use and understand and (c) take account of differences in disciplinary publication cultures (or, to put it in the prevailing jargon, they need to be “field-normalized”). As we noted eight weeks ago, the H-index meets the first two criteria, but is still of only limited value because it doesn’t meet the third.

Until now. Over the past year, we at HESA have been building a database which contains the H-index data of over 60,000 professors employed at 71 Canadian universities in all fields of study except medicine (which we excluded on the eminently practical grounds that we can’t for the life of us distinguish teaching faculty from clinical faculty on institutional websites – if anyone wants to enlighten us, we can include them too). This is a pretty demanding job, as you can imagine: there’s a lot that goes into checking and double-checking publication records to make sure they all correspond correctly to individual professors. We then used these records to look at how H-index scores differ across fields of study.

When we release the full document Wednesday, you’ll be able to see the results down to the level of the individual discipline, but for now the main results are below:

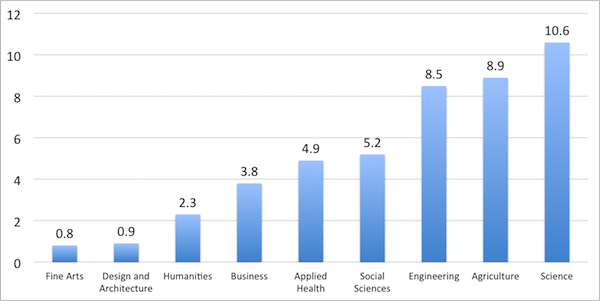

Mean H-Index Scores By Field of Study

As you’d expect, professors in science, agriculture and engineering have significantly higher H-indexes than other disciplines. After that, you’ve got the social sciences, which come slightly ahead of the applied health disciplines (the publications profile of academics in dentistry, nursing, kinesiology, etc, is really nothing like those in the biological sciences), followed by business and the humanities. Below that, there is design & architecture and fine arts, neither of which really seems to use the printed word as the primary means of scholarly communications; the median professor in these disciplines has either never published or never been cited in a scholarly publication.

You might think of this as a bit of a “so-what” finding. But it’s a big deal for two reasons: first, no one has ever done this systematically with the H-index before and second, now that it’s been done, it opens up an enormous amount of potential research on research and impact to be conducted – and we’ll be giving you a taste for the rest of the week.

— Alex Usher and Paul Jarvey

Tweet this post

Tweet this post